Sherwood Forest

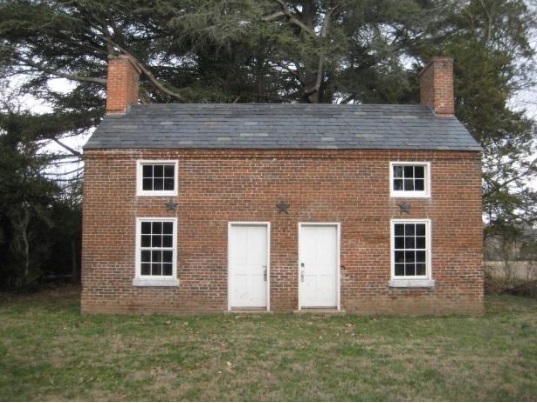

The land on which this home was built was originally owned by Mary Ball Washington, George’s mother, when she was just five years of age. She retained it until 1778. The land passed to a Ball descendant, Jane Downman, who married Henry Fitzhugh in 1837. The newlyweds constructed the house in the late 1830s or early 1840s. The house is beautifully situated on a hill about a mile from the Rappahannock River. Because of its commanding view, it was used during the Union occupation of Stafford in 1862-1863 as a balloon launch site for reconnaissance, as well as a picket-post and a field hospital after Chancellorsville. In 1867, Sherwood Forest passed out of the Ball-Washington family for the first time. There are many outbuildings on the premises: kitchen, enslaved quarters, smokehouse, and well house. More modern buildings on the hill such as barns, a dairy, silos, etc. reflect Stafford’s agricultural economy.

Jim Crow laws were any of the laws that enforced racial segregation in the American South between the end of Reconstruction in 1877 and the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950’s. For Stafford County, the Jim Crow era stretched into the 1970s.

In 1928, Sherwood Forest Farm was purchased by industrialist and philanthropist John Lee Pratt and his spouse Lillian Thomas Pratt. The Pratts chose to reside at their home near Falmouth, assigning the responsibility of managing Sherwood Forest to John’s nephew, T. Benton Gayle. Gayle stewarded the agricultural operations from traditional, diversified practices to a new, modern operation focused on dairy production. Under the traditional system, Sherwood Forest successful agricultural productivity was sustained by the labors of the enslaved, and post-emancipation, the former enslaved who chose to stay on for wages.

With the advent of ‘scientific’ farming practices in the late 1930’s and early 1940’s, the labor force shifted to whites. Farm manager T. Benton Gayle, by his actions, supported the attitude of the day that suggested ‘as agriculture advanced and was touted as more of a science, African American workers were not seen as capable or advanced enough to participate in this form of work.’ Instead they were limited to positions of servitude and were not given the opportunity to advance. The last African American family to work at Sherwood Forest, the Taylors, resided in an existing structure thought to be originally built as a duplex dwelling for the enslaved. As late as 1940, John Taylor, husband, father, and African American was listed in the census as “neg.”, his occupation ‘’house boy”.

T. Benton Gayle was employed as the Superintendent of then segregated Stafford County Schools (and King George County Schools) from 1925 to 1965, witnessing Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 Supreme Court ruling that “separate but equal” was unconstitutional. Gayle, who was said to be adamantly opposed to desegregation of the public schools, used the brick kitchen building at Sherwood Forest as his office for both the farming operations and his duties as Stafford County School Superintendent. Johnny Arthur White, an African American father, traveled alone up the long road to the kitchen building at Sherwood Forest Plantation, more than once, to ask T. Benton Gayle to desegregate the schools. Gayle refused. Stafford County Schools did not begin desegregation until 1960, a full six years after the Supreme Court ruling rendering segregation unconstitutional. Virginia schools were not fully desegregated until the mid-1970s.

With the sale of the property to the Greenlaw family in 1961, T. Benton Gayle was forced to leave Sherwood Forest Farm.