Clifton Chapel

For nearly a century, a little white frame building called Clifton Chapel was at the center of life in the Widewater area of Stafford. Relatively little is known of the early history of this structure. Withers Waller (1827-1900) donated the land from his Clifton tract for the sanctuary. The Clifton home stood on the Potomac River and Withers operated one of the largest seine fisheries in the region. He married Anne Eliza Stribling (1832-1903) of Fauquier County and six of their eight daughters were married at Clifton Chapel.

Exactly when the chapel was constructed is also uncertain. A diary kept by Nathaniel Waller Ford (1820-1880) of nearby Woodstock notes that in February of 1850 he had collected $15.50 for repairs to the chapel. Based upon construction techniques and this diary entry, the chapel may have been built in the late 1840s. The repairs undertaken in 1850 were completed by a local free black man named Barney Wharton (c.1792-after 1870), a carpenter who also built a new house for Nat Ford that same year.

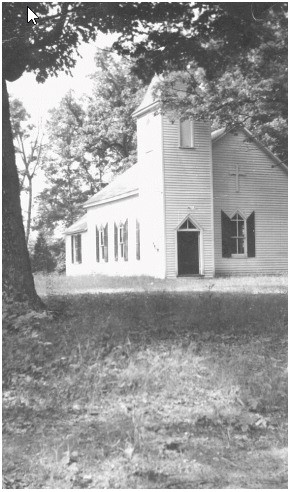

The first photograph probably dates from the late nineteenth century. Noticeably absent is the bell tower, which was a later addition to the building.

The need for the chapel was in large part due to the very poor condition of the county roads. As late as 1942, there were only two paved roads in Stafford, Routes 1 and 17. During wet weather, it was nearly impossible to get a horse-drawn wagon or cart over the muddy roads and people tried to stay close to home or they traveled on horseback rather than in wheeled conveyances. People in the Widewater area were serious about church attendance and worship and needed a chapel within a short distance of their homes. Clifton’s location put it within easy reach of most Widewater residents.

Ford’s diary revealed several interesting things about Clifton Chapel and the worship habits of his neighbors. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, many preachers were itinerant and traveled between multiple churches and chapels. At the time Nathaniel Ford was keeping his diary, worship services were held at Clifton every other Sunday. On the intervening Sundays, weather and roads permitting, Ford and his neighbors traveled either to Aquia Episcopal, Ebenezer Methodist, Chappawamsic Baptist, and even occasionally to a Dumfries church. They seem to have been little concerned with the denomination of the church, but had more interest in who was preaching and the tenor of the message. In his diary, Ford regularly noted his opinions regarding the preachers and their sermons.

During the Civil War, Clifton Chapel was used as a lookout for troops defending the shoreline and the railhead at Aquia Landing. In July of 1861, Confederate Colonel George W. Richardson brought two companies of the 47th Virginia Infantry to the chapel, which he called Camp Clifton. Richardson was responsible for defending several miles of Potomac River shoreline between the mouths of Chappawamsic and Aquia Creeks. Unlike today, there were few trees between the chapel and the river and the high hill provided an excellent view between the two creeks as well as the all-important R F & P railhead at Aquia Landing. Richardson’s troops remained at Camp Clifton until March of 1862 when they were called Fredericksburg and, later, to the Peninsula.

In April of 1862, Union troops invaded Stafford and likely also used the chapel hill for the purpose of watching over the Aquia Landing railhead. While the Union remained in Stafford for only fourteen months, they devastated the county. With few exceptions, the only buildings they refrained from destroying were the ones they occupied or those occupied by stubborn residents who refused to leave. Both Clifton and Aquia Church may have been spared as both were utilized by the army.

While the chapel remained standing after the war, it was damaged and in need of repair. In 1869, Anna Maria Mason Lee, wife of Sidney Smith Lee and resident of nearby Richland, wrote to her son, Henry Carter Lee, in Alexandria. She stated that what little money she had been able pull together was to go towards “rebuilding our poor Aquia & Clifton Church down here.” The local families pooled their meagre financial resources and personal energy and repaired Clifton and Aquia so that both were again able to serve the community.

On June 4, 1896, Clifton was officially dedicated and made part of the Episcopal Diocese of Virginia. Prior to this time, it had been independent and non-denominational. It remained the center of the Widewater community for many years and was the site of weddings, festivals, and picnics as well as worship services and Sunday School. Services were held there until the early 1960s when the building was shuttered, locked, and abandoned. With paved roads and better methods of transportation, folks in Widewater were able to drive to their churches and little Clifton Chapel was no longer necessary.

The chapel was neglected and vandalized until a small group of dedicated volunteers undertook to save it from collapse. They commenced work in 1992. Because many of these folks were still employed, most of the work was done on Saturdays. David Wirman led the group that included Jon Boeres, Milli Moncure, Col. John Scott, Chris Wanner, and John Weagraff. Funding for the restoration was through private donations. When the group finally completed their project, they had installed a new roof, repaired the interior pine wainscoting, rewired the building, added a furnace and air-conditioning unit, scraped, repaired, and painted the siding, installed insulation and a ceiling fan, sheet rocked, plastered, and painted the interior, refinished the wood trim, floors, and surviving pews, built a new altar and mantel, replicated the long-lost stained glass window over the altar, and placed an electric organ in the building. Clifton Chapel is now rented to St. Herman of Alaska Orthodox Church.