Roads

Paved roads are a relatively recent convenience in Stafford County, the first one not having been constructed until 1921.

From the early 1600s, Stafford’s rather unique geography impacted transportation. The county is bounded on the north by Chappawamsic Swamp, on the east by the Potomac River, and on the south by the Rappahannock River. Throughout colonial Virginia, the earliest transportation was by boat because there were few roads through the dense forests that abounded with Indians and wolves. Tidal Virginia is interlaced with hundreds of navigable tributaries that provided quick and easy access from one point to another. For many years boats were the preferred method of transportation in Virginia. In the mid-1600s the Virginia Assembly passed laws requiring the county courts to open and maintain roads linking the county courthouse, parish church, and the ferries. As population gradually increased very primitive roads were built from one plantation to another and from the plantations to the little towns that were established on the navigable waterways. Very slowly, a network of primitive roads was built, though boats long remained the favored means of transportation.

Most of the early roads either followed the banks of rivers, creeks, and runs, which were often flanked by level ground, or went along the tops of ridges where the drainage was better. Much of Route 218 (White Oak Road) was originally a long-established Indian path.

Building a road in the 1600s and 1700s meant little more than cutting a muddy path through the forest and underbrush. These paths were just slightly wider than a wagon. Many of the dirt roads were impassable during the rainy season and spring thaw. The mud commonly attained depths of two to three feet. One of Stafford’s most notorious sections of road was that part of Mountain View Road (Route 627) in the vicinity of Shelton Shop Road (Route 648).

Other roads were developed by heavy tobacco hogsheads. A hogshead was used in American colonial times to transport and store tobacco. It was a very large wooden barrel that might be rolled to a ship for transport to England. This rolling created roads from plantations to a wharf. A standardized hogshead measured 48 inches long and 30 inches in diameter at the head. Fully packed with tobacco, it weighed about 1,000 pounds.

Up until around 1920, these dirt roads were maintained by overseers of the road, also known as surveyors of the road. An overseer was appointed by the county court and was paid a small fee to maintain two or three miles of dirt road near his house. This man was not required to do the work himself, but was authorized to impress a group of local men, White or Black, to repair the road. This usually meant cleaning out drainage ditches, digging new ditches to drain large mud holes, and cutting back three limbs and trees that had encroached or fallen across the road. Because water transportation remained an important method of getting around, some overseers of the road were assigned sections of navigable waterways to maintain. It was their job to remove any trees, rocks, or other debris that interfered with boat traffic.

When Union soldiers wanted to move southward from Washington toward Fredericksburg, they were unable to get horses, wagons, and equipment through the Chappawamsic Swamp. Instead, they had to go west from Washington and come to Fredericksburg by way of the Warrenton Road (U. S. Route 17). After the Battle of Fredericksburg, Union forces moved west along Warrenton Road, then changed plans and tried to sneak back for a second assault on Fredericksburg. While still on the upper end of the Warrenton Road, it commenced raining and within a day or so the mud was three to four feet deep. Wagons and cannons were bogged and immovable and countless horses and mules either drowned in their harnesses in the mud or suffered heart attacks and died trying to pull the wagons through the mud. Their bodies were cast off along the sides of the road. Because of the mud, Union forces were unable to make their second attack on Fredericksburg and they lost an immense quantity of equipment and livestock.

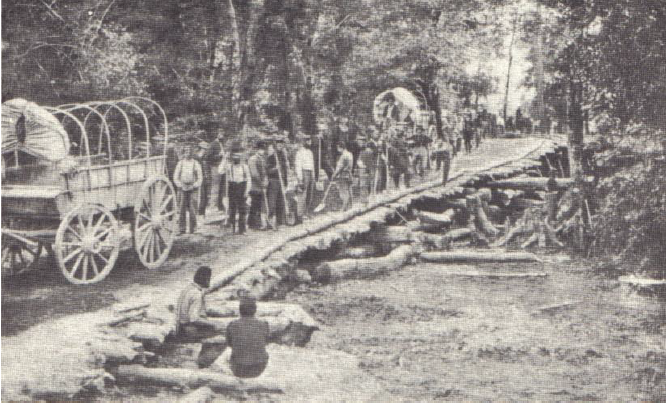

During the Civil War, Union troops attempted to make Stafford’s dirt roads passable by cutting small trees (6” to 8” in diameter) and laying the logs side by side along the road. Over the logs they placed a layer of tree limbs and branches, then covered it all with a layer of dirt. Roads built in this manner were known as “corduroy roads.” Because of the cutting of thousands of trees for corduroy road construction and thousands more for cooking and heat, the Union army nearly denuded Stafford and the stands of timber weren’t large enough to cut commercially again until the late 1800s. The nearly complete removal of the trees also resulted in a massive loss of topsoil, a condition from which we still suffer today.

The state of Virginia didn’t establish a centralized department of roads until about 1917. The first paved road in Stafford was U. S. Route 1, known since the 1840s as the telegraph road. A relatively passable “all weather” road wasn’t built through Chappawamsic Swamp until about 1918 and from that point until the mid-1960s this was the primary north/south land route between Maine and Florida. Route 1 was first paved with concrete, which remains beneath the asphalt now existing. The present U. S. Route 1 follows roughly along the old telegraph road, though many of the curves and meanders were straightened in the early 1920s when the road was widened from two lanes to four. A few sections of the old road survive, these being George Mason Road (Route 660), Route 637 that still retains the name “Telegraph Road,” Derrick Lane (Route 697), Bell’s Hill Road (Route 631), and Forbes Street (Route 627).

By 1942 Stafford had only two paved roads, routes 1 and 17. Application of asphalt on back roads was a slow process that continued into the 1960s and 1970s. There are very few gravel roads remaining in the county.

Sources:

- Eby, Jerrilynn. Men of Mark: Officials of Stafford County, Virginia, 1664-1991. Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, Inc., 2006.

- Fredericksburg Star

- July 27, 1886, “Stafford Roads”

- Free Lance

- Jan. 15, 1898, report on the condition of Garrisonville Road

- June 15, 1899, bridge to be build across Aquia Run

- July 14, 1910, road to courthouse nearly impassable

- Free Lance-Star

- Jan. 11, 1921, “Chappawamsic Completed”

- Harrison, Fairfax. Landmarks of Old Prince William. Baltimore, MD: Gateway Press, Inc., 1987.

- Tower, Capt. F. S. Geneva (New York) Times, October, 1919. “By Auto to Florida: Capt. F. S. Tower Writes Entertainingly of His Experiences en Route—Is Now on the Way North Again.”