World War II

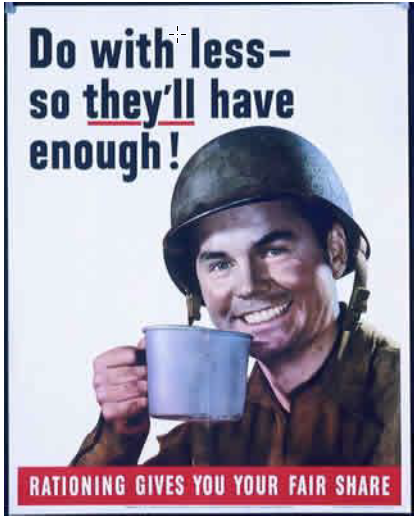

Black Outs – Rationing – Saving Stamps – War Bonds

by Marion Brooks Robinson

Stafford County joined the rest of the nation in responding to World War II. Citizens were enrolled in Community Civil Patrols. County citizens volunteered as War Bonds salesmen, going to homes in their neighborhood to encourage financial support. Schools began selling savings stamps and a County Rationing Board was formed. My business class at Falmouth High School was put to work typing names and addresses on individual ration books.

“War materials” included gasoline, sugar, nylon, leather, etc. Civilians not working for the government or other vital agencies such as hospitals or fire companies were allowed only two gallons of gas per week. Both men and women could get stamps for only two pairs of shoes per year. Children were allowed four pairs because young feet soon outgrew shoes.

Students could buy savings stamps for 10 cents each. You collected them in a stamp book and when you had stamps that added up to $18.80 you could use them to purchase a bond which could be redeemed for $25 after 5 years. Other bonds were usually in $50 or $100 denominations. Stafford’s volunteer salesmen sold more than $50,000 worth in just one year. Remember at this time the population of Stafford numbered only about 8,000 persons.

In the early months of 1942, following the attack on Pearl Harbor, citizens were warned about the possibilities of air raids by the enemy. “Air Wardens” were appointed and “drills” began. Fire stations would sound the warning, a long uninterrupted blast of the firehouse siren. This meant “blackouts” in all homes and businesses. My mother also insisted that my brother and I join her to sit quietly in the living room until the “all clear” was sounded. I think she was most worried about accounting for our behavior in the newly darkened world, rather than having the enemy find us. Wardens checked to see that everyone was turning off lights and those who failed to comply could be fined. The end of the “blackout” period was announced by a series of short blasts from the firehouse siren.

When World War II ended and the “Cold War” began, local citizens were urged to prepare for a “worst case scenario” by building “fall out” shelters. Dr. Summner, one of my teachers at Mary Washington College, actually spent more than $3,000 on an elaborate underground retreat. I got in trouble at a citizens meeting at Stafford Courthouse when I spoke to declare shelters in Stafford “absurd.” I stated that an atomic bomb dropped on the nation’s capitol, considered the number one target, would have a fifty mile “fireball” in which no life would survive. None of Stafford County was more than 48 miles from D.C.

(Stafford resident Richard Chichester told me that when he was going to Falmouth High School at the current Ray Grizzle Building, Mrs. Melchers of Belmont came to the school and said that it was very important that people buy bonds and stamps to help the war effort. He recalls that she had an English accent. He felt that even though she was an American, she lived overseas for so long that she developed such an accent. He still remembers that she said they should by ‘staaahmps’.

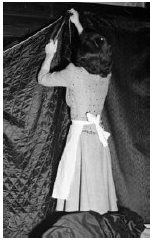

Marion Brooks Robinson, the author of the above article, recalled that Mrs. Melchers went to the drama department of Mary Washington College to have a play for Dutch relief. She felt that so much of the Netherlands had been destroyed during the war that she wanted to do something to help. Since Marion was a drama major, she asked Marion to emcee the play. She also asked her to wear a dress that she wore in one of her husband’s paintings.

The above two remembrances came from interviews done in February and March of 2011 by Jane Conner.)