Quantico Condemnation

War came unexpectedly to all Americans on December 7, 1941. In 1942 world events profoundly impacted rural Stafford County. The Marine Corps, on the brink of the Guadalcanal offensive, desperately needed to expand their training facilities at Quantico to accommodate the large influx of soldiers bound for deployment in the Pacific. In 1918 the Marines had taken 5,300 acres in Prince William County, but now found this inadequate for their training needs. Very quietly, the Department of the Navy began making plans to condemn some 51,000 acres in Stafford, Prince William, and Fauquier Counties for use by the Marine Corps. The bulk of this, about 30,000 acres was in Stafford. On October 6, 1942, the U. S. Government filed a condemnation order for the property. Residents had until October 26 to leave.

The Stafford portion of the condemned property, by far the largest of the three parcels was divided into two tracts, one of 20,000 acres, which was primarily to the west of U. S. Route 1, and 10,000 acres east of Route 1 that included the northern part of Widewater and stretched all the way to the Potomac River. The northeast corner of the tract, which stood at the junction of Chappawamsic Creek and the Potomac River, was the site of the ancient plantation known as Dipple. The Marines had acquired part of this around 1918 and built an airfield there. To Stafford as a whole, the 30,000 acres condemned had represented about 1/6 of the total area of the county and a comparable amount of lost tax revenue. The condemnation impacted about 750 people in some 150 families on 20,000 acres and about 500 people in 100 families on the remaining 10,000 acres.

Amazingly, there was little protest against the government by those who were losing nearly everything they knew. One can imagine the uproar if the same events occurred today. There were likely several reasons for this lack of response. To begin with, there was so little time between the initial notification and the deadline to evacuate. People also felt a strong sense of patriotism toward U. S. involvement in World War II. Finally, the county hadn’t yet recovered from the effects of the Great Depression and those now facing eviction hadn’t the money to fight a court case they were unlikely to win. Most residents accepted the government’s actions as an unpleasant but inevitable fact of life and rebuilt their lives as best they could. Some never recovered from the experience, but the civilians moved out and the Marines moved in.

Some of those families had sent sons to fight in the Civil War, endured Union occupation, and sent sons to Cuba in 1898 and France in 1917-1918. Now they were being dispossessed of their homes and livelihoods. Among those who were evicted was William Weedon Cloe, a farmer, veteran of the First World War and a member of the Stafford School Board. The Washington Post of October 8th contained an article entitled “The War Comes Home to Farmers in Nearby Virginia.” Describing Cloe as “solid and substantial,” it quoted him:

I went through the last war, volunteered as a matter of fact the day after the war was declared [it was actually the same day], and if they need my farm to get through this war, then they can have it…I’m classified 3-A now and if they need me for this one, I’m ready.

Cloe probably did not speak for all of his neighbors, but the effect of their sacrifice was the same. They gave up their homes for their country. The farm, about 160 acres in 1942, now lies mostly under Lunga Reservoir. Another Cloe home, “Laurel Spring,” which had been purchased by William S. Cloe from the Burroughs family in 1863, had burned in 1942, prior to the Quantico expansion.

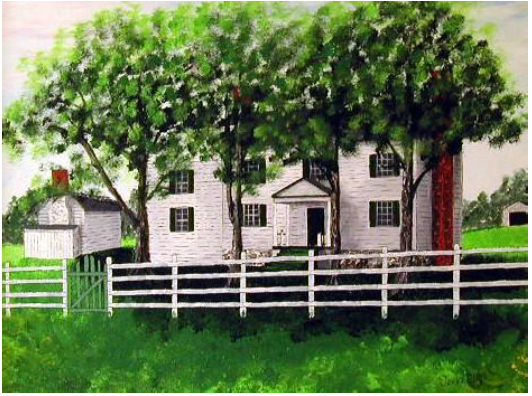

To understand Cloe’s loss, we may want to delve into the specific history of his farm. “Laurel View,” associated with the Stark and Cloe families, was built about 1840. It had been taken over by Union troops during the Civil War. Stafford author, Jerrilynn Eby MacGregor, writes:

In 1923 William Weedon Cloe purchased the property from the Starke heirs. He and his wife effected many repairs, replaced dilapidated outbuildings, and improved and modernized the house. They opened a dairy which later became a Grade A Retail Permit operation. Some of the modernizations included the installation of running water (courtesy of a gasoline-powered pump), a carbide gas lighting system, and a battery-operated telephone system carried on the barbed wire fence between and the adjoining farm.

The sacrifice of the families losing their homes should be appreciated as part of the human story of World War II. A number of the lost homes were historically significant, and that history was also lost. They included some of northern Stafford’s oldest home sites. Some were “Chopawamsic Farm,” “Dipple,” “Clermont,” “Somerset,” “Rectory,” “Chelsea,” “Providence,” and “Bloomington.” Also lost were “Stafford Springs,” “Locust Grove,” “Marble Hill,” “Mount Olive,” “Spring Dale,” and “Springfield.” Six churches and many smaller farms were also lost. “Chopawamsic Farm” and “Dipple” were associated with the youth of founding father George Mason (IV). George Mason (II) had lived at “Chopawamsic Farm” after 1709; the property ran from current Boswell’s Corner on the west to “Clermont” on its east. The main house, constructed using local sandstone, was inherited by George Mason (III), who lived with his family on Aquia Creek until his accidental drowning. Mason’s widow then moved her family to “Chopawamsic Farm.” Remnants are along George Mason Road.

Another lost home, associated with Aquia Church, was “Dipple,” a glebe farm (i.e. owned by the parish). Rev. Alexander Scott also tutored George Mason (IV). Scott, born in Dipple Parish in Scotland, purchased the property in 1724. Owing to a diversion of the Chopawamsic Creek to build an airfield, much of “Dipple” was submerged. “St. Mary’s” was believed to be a part of “Dipple.” “Clermont” was acquired by Rev. John Moncure, a Scottish immigrant, in 1727. He built a house which passed to John Moncure II in 1786 and to John Moncure III in 1796. “Clermont” remained in the Moncure family until about 1886 when it was sold to a George Middleton. In 1920 it was purchased by Frank Hill. The house burned in 1940 and was rebuilt in 1941 only to be confiscated in 1942.

The churches lost in 1942 were: Bellehaven Missionary Baptist Church; Church of the United Brethren in Christ; Massadonia Baptist Church; Mount Zion Baptist Church; Providence Church; and Stafford Store Baptist Church.

Missouri Mills, a Stafford mill which had operated for 150 years, and Belfair Mills, which operated until the original establishment of the Quantico Base in 1917, were in the area. Other mills on the current Quantico base were Stone’s Mill,

“Somerset,” originally part of “Clermont,” apparently remained in the Moncure family until it was confiscated in 1942. “Rectory,” associated with Rev. Jaquelin Marshall Meredith, was owned by Moncures at the time of the 1942 expansion. “Chelsea,” built in 1819, is another Widewater home associated with John Moncure and George V. Moncure; it was also included in the Quantico expansion. “Providence,” adjoining “Bloomington,” was associated with the Wallers and Fords and, after the Civil War, with Rev. Jaquelin Meredith. Also lost was “Stafford Springs,” once a Stafford resort and Confederate spy center. It was associated with the Blackburn, Fitzhugh, Dickinson, Cannon, Brawner, and King families prior to 1942. “Locust Grove,” home to the Gaines and Alexander families, was located near Bellfair Mills overlooking Stafford Run.

Less is known of some other homes lost in Quantico’s expansion: “Marble Hill” was on the north bank of Beaverdam Run; “Mount Olive,” an 1859 farm owned by Hannah Stone’s heirs; “Spring Dale,” named for the numerous springs on it, Tolson’s Mills (2), Master’s Mill (Wigginton Mill), Purcell’s Mill, and Dr. Wheat’s Mill “to name a few.”