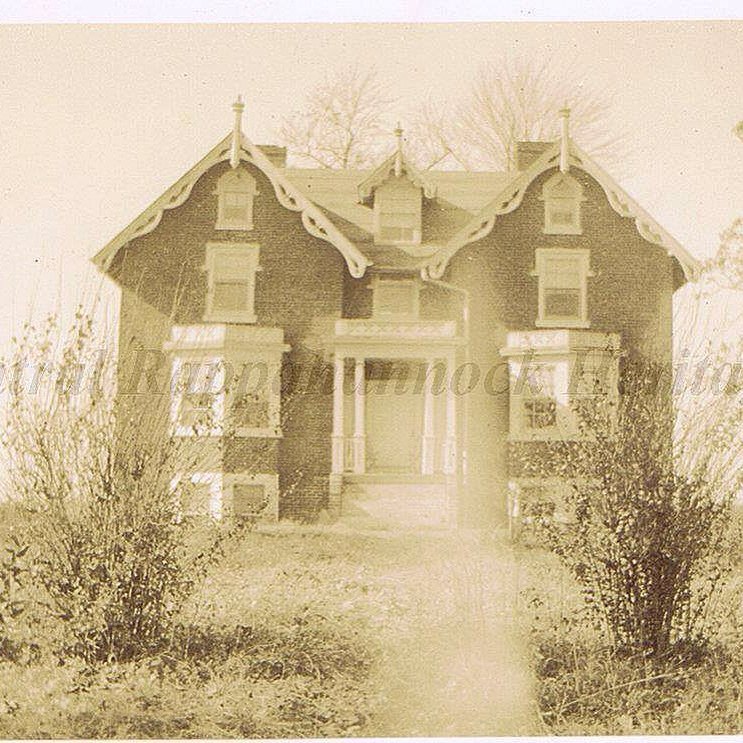

The Ariel Foote House (Hartwood Manor)

The house that is now known as Hartwood Manor was built in 1848 by Ariel and Julia Foote, who moved to Stafford County from Burlington, Connecticut, near Hartford, in 1836. The Footes had no family in Stafford, but Virginia was not an unknown place to them. Ariel’s older brother, Jairus, had lived in Alexandria, but he died there in the 1820’s. All available records place the family on this land prior to the construction of the brick house, possibly in a more modest dwelling whose location is lost.

The Footes built their new house in the Gothic Revival style, which was popularized at that time for rural homes by upstart New England architects who declared that the Gothic Revival suited a dynamic personality. Exterior of the house draws heavily on the designs that were commonly available in pattern books in New England. It was originally built in an L-shaped plan with three rooms on each level.

Stafford County personal property tax records show that, the Foote family began owning enslaved people in 1839. The number of individuals listed on their tax declaration varied year by year, but they never paid taxes on more than four. Construction of a house this grand and operation of the farming and the commercial lumber operation on the 800+ acre property would have required a more substantial work force, and additional labor in the form of leased, enslaved workers was utilized. The identities of all of these people are unknown except for one … Anthony Burns.

According to Albert J. von Frank, author of The Trials of Anthony Burns: Freedom and Slavery in Emerson’s Boston, Ariel Foote leased Burns from his owner, Charles Suttle of Falmouth, in 1849 to operate his steam-powered saw mill. During this time, Burns severely injured his hand while operating the large steam-driven mill. Disfigurement caused by this accident was an identifying characteristic presented as evidence of Burns’s identity during his fugitive slave extradition trial in Boston in 1854.

Burns described life on the Foote farm to Charles Emery Stevens, who published Anthony Burns: A History in 1856. Stevens wrote, “The new home did not prove to be very agreeable. Foote and his wife were Yankees, and they were … among the severest taskmasters of the south. Young slaves were beaten by the mistress without mercy. … Besides [this cruelty] niggardly fare was doled out, and occasionally, in a fit of gloomy merriment, Anthony would hold up to the sun his thin shaving of meat to show what a transparent humbug it was. His lot, however, was not one of unmixed evil, for, through the friendly teaching of a young daughter of his employer, he was enabled to make some further progress in his cherished pursuit of knowledge.”

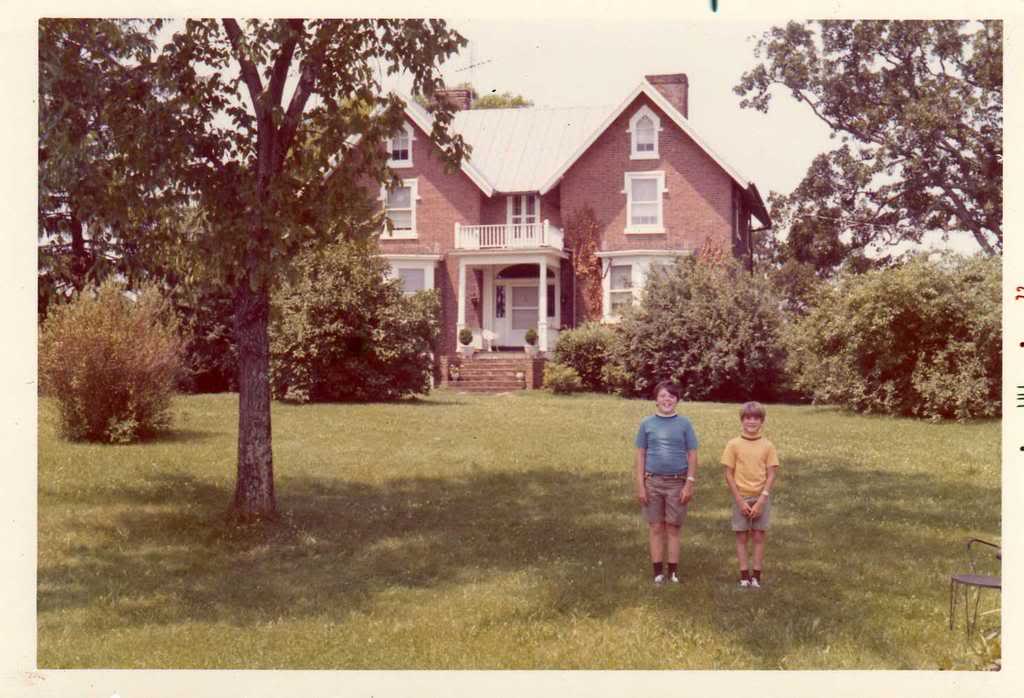

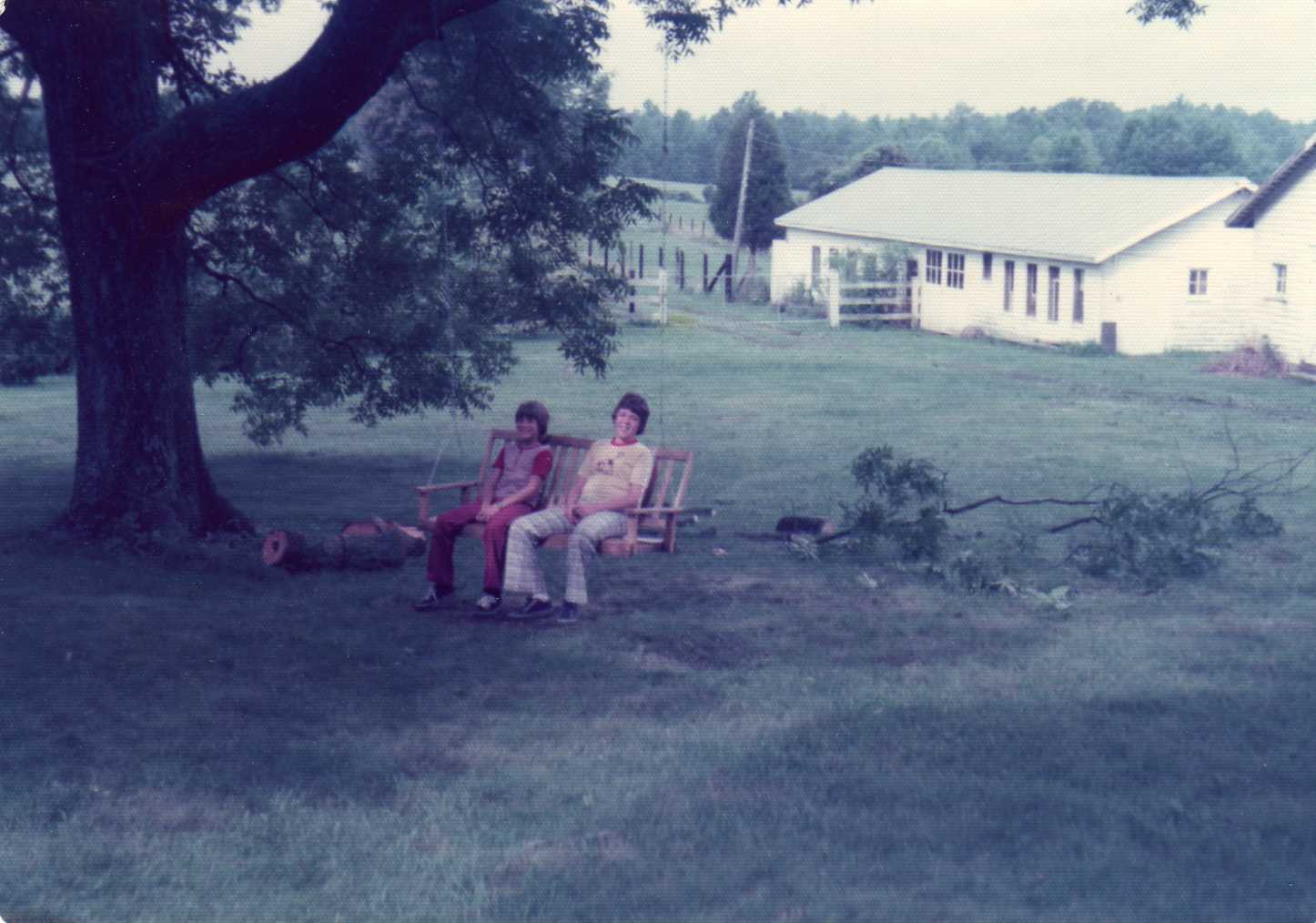

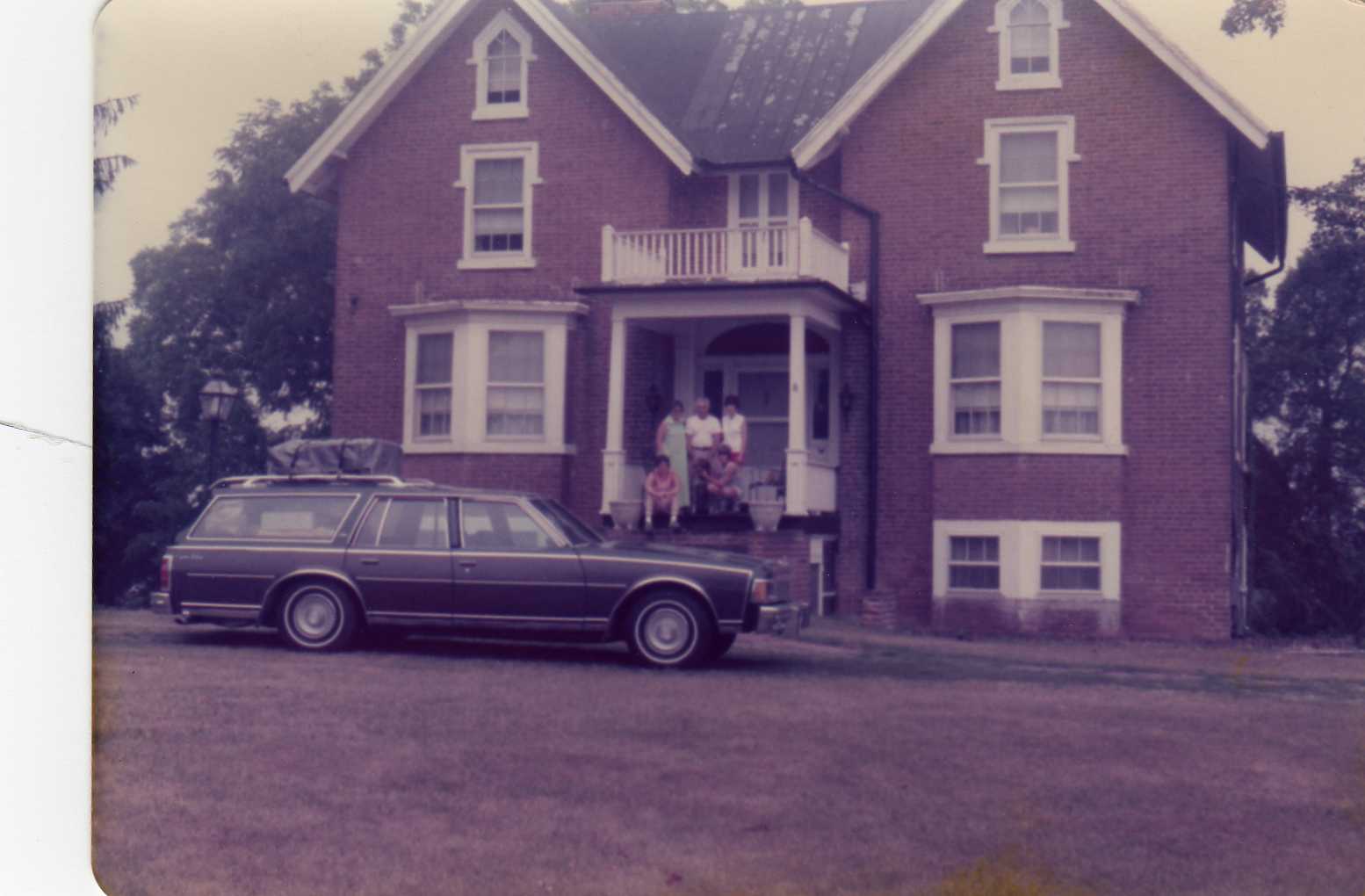

Old homes like Hartwood Manor have evolved over the years. The current owners received some 1970s snapshots of their house from a family whose uncle owned it. They show a boy in the yard, surrounded by trees and bushes long gone, a porch railing that’s been removed, and a driveway that didn’t run where it does today. These weren’t meant to document the house—just capture a moment—but they reveal a Stafford that’s faded away.

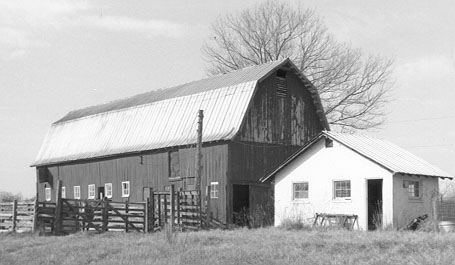

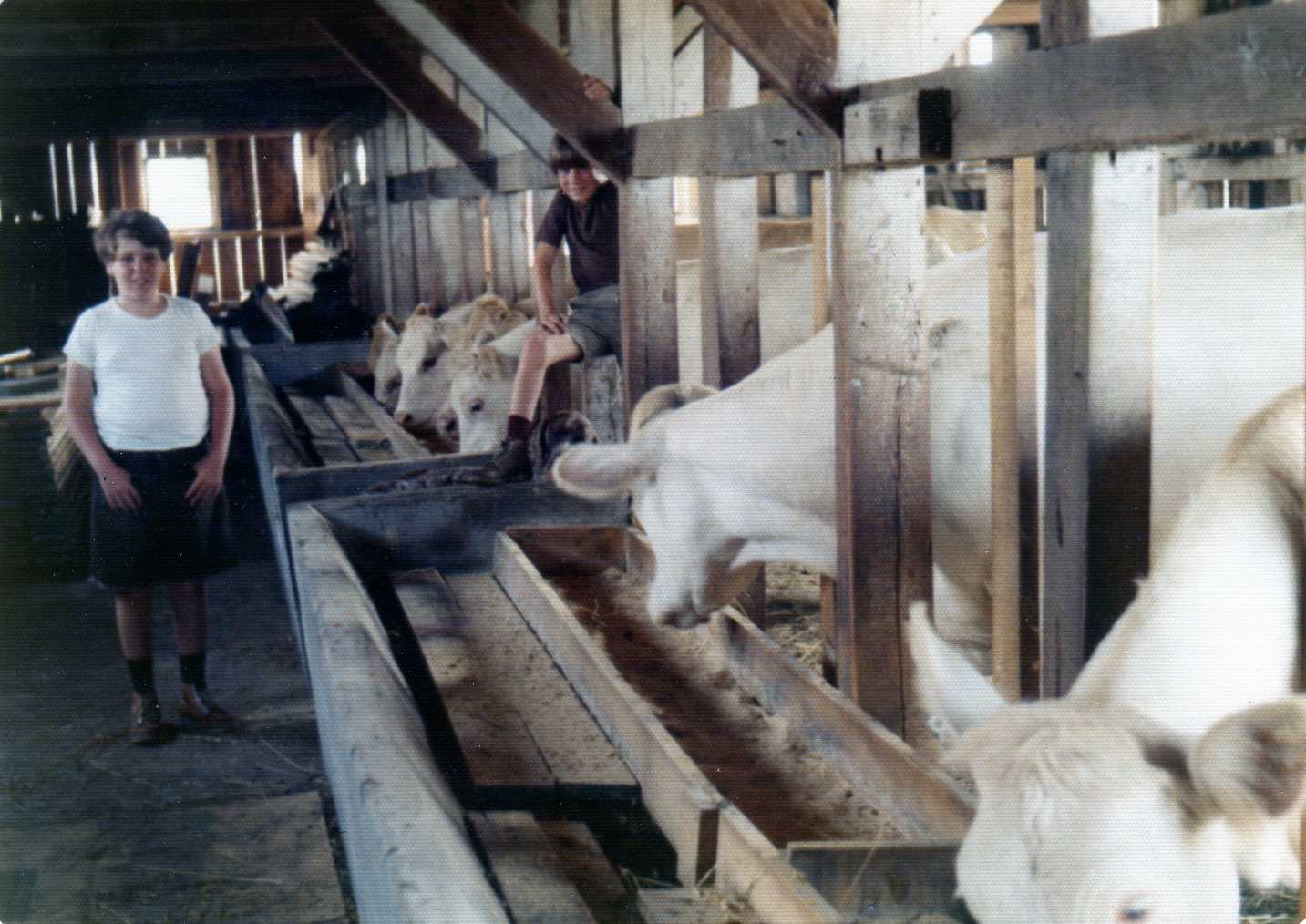

Inside of barn at Hartwood Manor (1975)

Hartwood Manor backyard showing large pecan tree and utility building now gone (1975)

Hartwood Manor (1976)

Hartwood Manor (1976)