Taxes and Tithes

Tobacco as Currency

Prior to the American Revolution, paper money and coins were in extremely short supply and tobacco was routinely used in place of cash. This versatile plant, then, was exported, smoked, and served as currency. Colonial Virginia produced a variety of goods, chiefly pitch, tar, turpentine, iron, lumber, hogshead and barrel staves, shingles, wheat, flour, corn, beef, pork, tallow, fish, butter, geese, and turkeys; however, without question its most valuable product was tobacco. Various types were grown, but only two varieties were received at the official warehouses, Oronoco and sweet-scented. Oronoco was the type most commonly grown in the Stafford region.

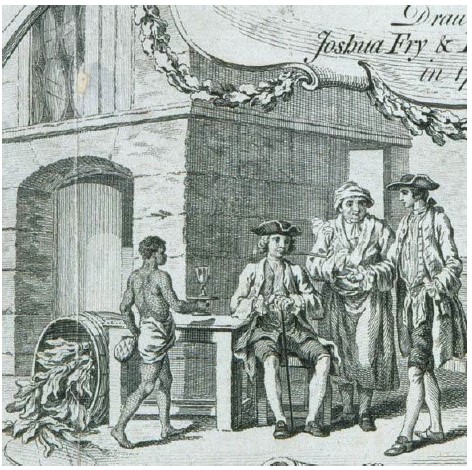

Most of the tobacco produced in colonial Virginia was carried by sailing vessels to England and Scotland where it was sold in shops all over Europe. As the ships arrived in the Virginia ports somewhat infrequently, the tobacco, which was stored in very large barrels called hogsheads, had to be stored in warehouses until a ship came to pick it up. Because of its value as an export, the English government collected a tax on each hogshead stored in the warehouses.

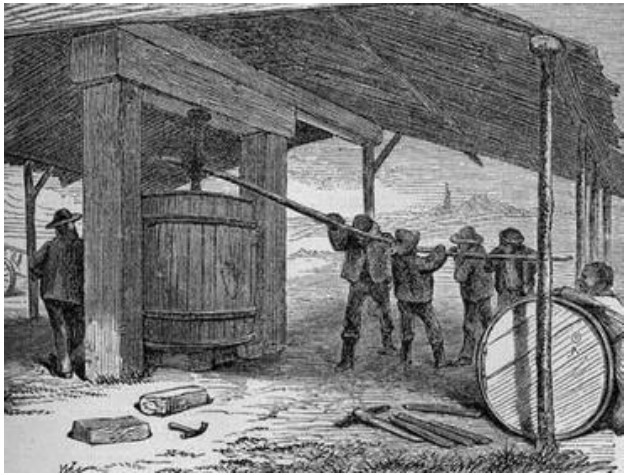

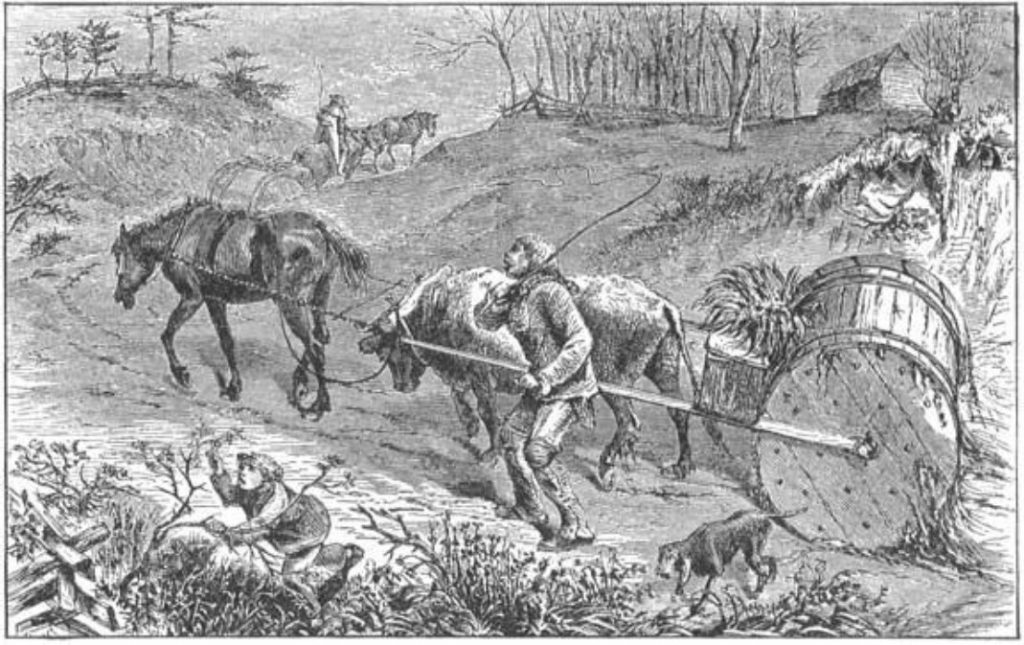

By law planters were required to bring their tobacco to the official warehouses for grading and the collection of the tax. Transporting the tobacco from plantation to warehouse was often difficult and sometimes resulted in damaged tobacco. An act of 1730 ordered official inspection warehouses to be built 12 to 14 miles from one another on all navigable water. Once the tobacco was harvested, it was dried, stripped from the stems, and packed in hogsheads. Tobacco thus packed was called “crop tobacco.” The tobacco was then transported to the nearest warehouse for storage until it was either sold or exported.

Transportation of the heavy barrels was accomplished by running a long pole through the center of the barrel from one end to the other, leaving a handle protruding from each end. This allowed the hogshead to be rolled, the handles being manned either by two laborers or attached to the harness of an ox. Trails known as “rolling roads” were created from outlying plantations to the tobacco warehouses. These trails were just slightly wider than the hogsheads and a few remain marked on modern maps. By an act of Assembly, each hogshead was required to weigh at least 950 pounds but some weighed as much as 1,500 pounds.

Once the tobacco arrived at the warehouse, official inspectors opened each hogshead, graded the contents, weighed each barrel, and marked each with an official warehouse stamp. They also collected a special tax of two shillings on each hogshead received at the warehouse. The inspectors then issued to the planter “crop notes” for the value of the tobacco brought and stored at the warehouse. These notes were purchased by merchants who not only ran local stores but also often worked for large tobacco companies in England and Scotland. These crop notes often passed as cash from person to person before the tobacco was actually sold and exported. The notes served as a means of buying land, purchasing store goods, and paying taxes.

Because tobacco doubled as cash, maintaining a consistently high quality was essential to the stability of the colonial economy. In an effort to limit the amount of inferior tobacco, a law required tobacco inspectors to burn any tobacco not meeting well-defined standards. As a result, planters tried to sell their low-quality tobacco secretly rather than have it destroyed. “Trash tobacco” could be the result of a number of problems ranging from a poor growing season, insect damage, too little water, too much water, harvesting too early or too late, or damage incurred during hauling of the hogsheads from plantation to warehouse. In 1765 the county justices were authorized to issue warrants for the search and seizure of unlawful tobacco and impose fines for violating the grading laws.

By 1800 tobacco was losing popularity as a medium of exchange and by 1805 most of Virginia’s tobacco warehouses were closed. Paper money replaced tobacco notes and the dollar replaced the British system of pounds, shillings, and pence.

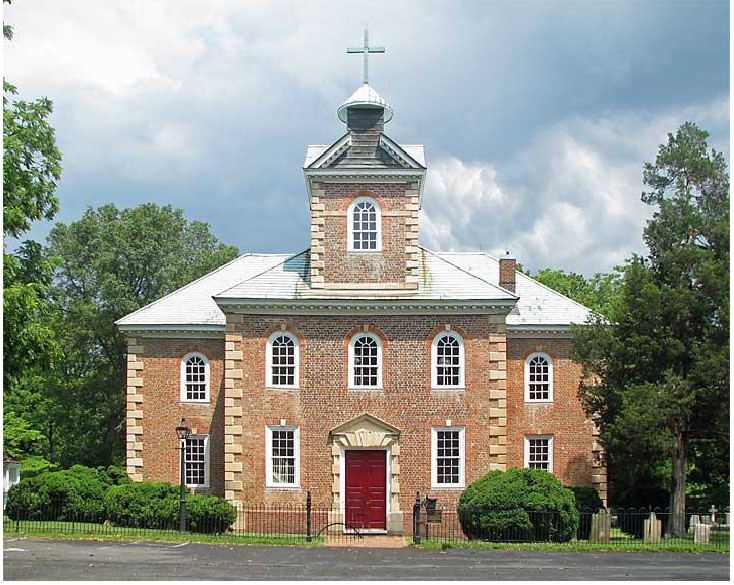

Parishes and Vestries

Virginia was established as a Protestant colony and was, according to English tradition, divided into areas called parishes. The bounds of the parishes often corresponded with those of the counties. The parishes were run by administrative groups called vestries. These vestries usually consisted of twelve free, white, land-owning, literate males who were responsible for building churches and chapels, hiring and paying ministers, purchasing and managing parish-owned farms called glebes (where the ministers resided), as well as overseeing many social services now managed by individual county governments. These latter functions included, but certainly were not limited to, housing and feeding of the elderly and indigent, providing foster care to very young orphans, binding out older children as apprentices to learn trades, and disciplining those who broke a variety of social or religious rules such as drunkenness, adultery, swearing, failure to attend church, etc. Orphaned children were normally placed with a planter or tradesman where they were expected to remain until they reached the age of 21. Children could be taken from homes where the parents were unable to care for them or from parents who were likely to encourage their offspring along bad courses. The vestry was to supervise the care given these children in their foster homes and was required to notify the courts in cases of abuse of neglect. Church attendance was mandatory and those who failed to attend without reasonable cause could be fined.

The vestry was also expected to oversee all cases of extreme poverty. A few counties, including Stafford, established a fund to care for the helpless poor. Almshouses, or poor houses, were built to feed and shelter those who had nothing. Sometimes, a poor person was lodged in the home of a citizen willing to accept him for a small sum. It should be remembered, however, that extreme poverty was rare in colonial Virginia. Food was plentiful and the opportunities for earning a livelihood were numerous. All but the most aged and infirm could do simple tasks such as stripping tobacco leaves and anyone strong enough to lift a hoe could weed corn for a living. The duties of the vestry were essential to the efficient operation of the county.

It required a good deal of money to conduct these activities and the vestries were empowered to set levies or taxes. County residents paid three types of levies: parish, county, and public. Because the vestrymen were usually well acquainted with individuals that attended church, the vestry could excuse any parishioner from paying the parish levy on the grounds of disability, age, or some physical defect that prevented that individual from working in the fields or otherwise earning an income.

The vestry usually met in October as by that time the tobacco crop had been harvested, cured, and was ready for export. In order to determine the amount of the levy each household would be required to pay, a list was made of all parochial expenses, adding to this the expenses incurred for collection of the levy and administration. This amount, figured in pounds of tobacco, was then divided by the number of tithables residing in the parish. Tithables were defined as all slaves 16 years of age or older and all white males 16 or older. The head of each household was responsible for paying the taxes on all tithables under his care. Tax payers had the right of appeal to the General Assembly if they believed that the levies were oppressive. This occurred in Stafford on at least two occasions—once when the vestry decided to build Aquia Church and a second time when the justices decided they needed a new courthouse. It was the responsibility of the county sheriff to go to each household and collect the parish, county, and public levies, then turn over the tobacco (paid in the form of tobacco notes rather than actual barrels of leaves) to the appropriate authorities.

Prior to the American Revolution, Virginia vestries represented the Church of Virginia, which was merely an extension of the Church of England. In the decade preceding the Revolution, Virginians became increasingly dissatisfied with English government. As an authorized taxing body, the parish vestries often felt the growing wrath of the citizens. Thus, when the colonies won their freedom, one of the first official acts was to dissolve the old parish vestries, remove their taxing authority, and sell their property. The social services formerly provided by the vestries were assumed by the county governments.

Sources:

- Bruce, Philip A. Institutional History of Virginia in the Seventeenth Century. NY: G. P.

- Putnam and Sons, 1910.

- Eby, Jerrilynn. Men of Mark: Officials of Stafford County, Virginia, 1664-1991.

- Westminster, MD: Willow Bend Books, 2006.

- Mapp, Alf J., Jr. The Virginia Experiment: The Old Dominion’s Role in the Making of

- America (1607-1781). Richmond, VA: Dietz Press, Inc., 1957.

- Porter, Albert O. County Government in Virginia: a Legislative History, 1607-1904.

- NY: Columbia University Press, 1947.