Captain John Smith

Captain John Smith and the Early Citizens of the Tidewater Region

Tidewater, Virginia has a long history of occupancy by FFV’s (First Families of Virginia) noted for their generous hospitality. Captain John Smith’s encounters with some of the first families along the Rappahannock found that not all were quite so gracious back in 1608.

We are fortunate to have first-hand knowledge of Indian families living along the rivers of the Chesapeake basin from the detailed journals of Captain John Smith published in a “General History of Virginia.” Spanish maps as early as 1520 showed the Chesapeake B ay area and the rivers emptying into it. Smith, using these maps, made extensive explorations looking for precious metals and the fabled “Northwest Passage.”

His first trip up the Rappahannock River began on June 16, 1608 and it almost met with disaster. One of the two large flat-bottom boats carrying nine explorers ran aground on a sand bar in the wide mouth of the river. Smith reported that schools of fish surrounded the boats and they began spearing them with the points of their swords. Seeing a strange looking specimen, the Captain speared a sting ray and was immediately struck on the wrist by its whip-like tail. “There was great pain, but no blood wound only a round blue spot.” The leader of the expedition fell into the bottom of the boat as though dying. He was losing his breath and lapsing into unconsciousness. With what he thought were his last words, he ordered a grave dug for him on the southwest shore of the river just as soon as the tide lifted the boat off the sand bar. By nightfall the turning tide, Smith’s death-like pail had lessened and Smith seemed to be recovering but the expedition decided to turn back to Jamestown and did not start back up the river for another month.

This second attempt to explore the Rappahannock was not without its adventures. Early in the second trip good fortune came in the form of a guide, Mosco, who they met when they pulled into shore about 30 miles below the present town of Tappahannock. Mosco had most recently lived with the Potowomacs at present-day Marlborough Point in Stafford County. Not only did he speak the Algonquin language of the Powhatan tribes but fluent French, so he was the perfect interpreter since several English members of the party also spoke French. Descriptions say Mosco had a full black beard, unlike other Indians, and was referred to as “The Frenchman.” This may have had its explanation in French Canadian explorer ancestry. Mosco’s first suggestion may have saved the expedition. He proposed that they fit the boats with breastworks on either side. These were woven, under Mosco’s direction from silk and grass and wild hemp growing along the river. The shields rose above head height when the men were seated. There were slits for viewing the shores but they prevented death during several unfriendly encounters when hails of arrows were fired at them from the river banks. The Rappahannocks (sometimes referred to in the journals as the Tappahannocks) were particularly war-like at this time. Tribes to the south had recently stolen three of the |Chief’s wives and any approaching stranger became an enemy.

The first death of an Englishman, however, came not at the hands of the Indians, but from fever. Mr. Richard Featherstone came down with the fever as they explored a river just about two miles below the fall line (believed to be the present-day Scotts Island adjacent to Chatham Bridge) He died the next day and the journal says the body was rowed to the northeast shore of the river, an area now in Stafford County. His burial took place on the flats beside a small run now believed to be Claiborne’s Run, with “proper words being spoken above the remains.” This is the first record of an Englishman buried outside the Jamestown area. In his honor Smith named the indentation near the mouth of the stream the “Featherstone Bay.” Geologists believe there was a deep indentation at the mouth of the run in the early 17th century that later silted in as the area around it was put under cultivation.

The real encounters with the first families of America were to come as Smith and his party reached the fall line in the Rappahannock River. Here he found two different groups with distinctly different languages living only several miles apart. On both banks above the fall line lived Manahoc Indians who spoke a Siouan language. The Seacobecks on the osyuth side of the river had encampments running from present day Mott’s Run down to Fredericksburg. The Manacans occupied the north side of the Rappahannock from the hills were Belmont now stands, west to Hartwood.

They had built stone weirs in the water right at the beginning of the fall line and with willow basket traps at the end of each weir they wee taking great numbers of fish from the Rappahannock. According to the journal, the Indians were smoking fish on long slender green poles over smoldering wood fires, kept burning in sandy holes along the river banks. Mosco, who also had some understanding of the Siouan language, reported that they were trading these smoked fish with tribes beyond the mountains to the west (Blue Ridge).

The second night the Englishmen spent above the fall line they were attacked by a Manahoc war party. Smith recorded that they were “forced to discharge weapons.” This frightened off all but one, a brave named Amoroleck who fell wounded by the firing. Mosco eagerly asked to be allowed to finish him off with his ax and later looked on with disgust as the white men treated Amoroleck’s wounds and the next day returned him to the Indian encampment on Belmont Hills. The brave proved to be a nephew of the Chief and he expressed his gratitude by ordering a feast in honor of the strangers.

At the gathering he presented Captain Smith with one of his strongest best made bows and a bundle of arrows tied together with a deer hide strip. He ordered the Monocan braves to hang their bows from the branches of the trees. Surrounding the feast site as a token of good faith, hospitality that would have equaled that of Tidewater planters a few centuries later.

After visiting with the Manahocs on both sides of the river, Mosco led them to a large village which was described as being on the north side of the Rappahannock about a half mile below the fall line. Smith described the village as surrounded by flat fields, high on a hill above the river. This closely fits the description of the land which makes up the present-day Brooks Park and Chatham sites.

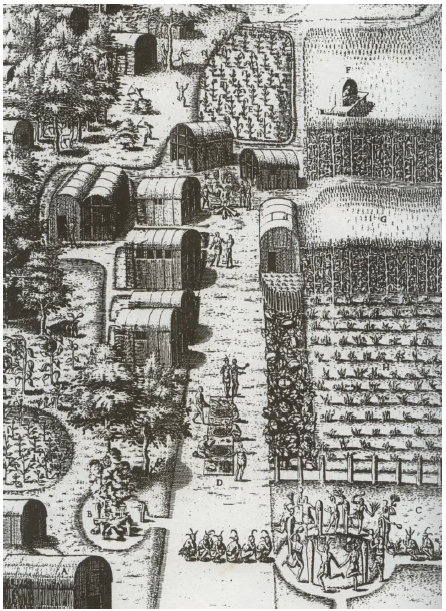

This was the village of the Massawteck tribe, a large village of more than 50 dwellings, plus storage and lodge buildings of considerable size. When I say buildings, I am referring to the dwellings as described by Smith and used by most of the Powhatan Indians in the Tidewater area. They were more or less permanent dwellings made by sinking large poles in the ground, bending green poles between them to form a roof base, and then covering the frames with closely woven grass mats.

According to Smith the main building was fenced with a tall palisade made of large poles implanted side by side around the area. Gardens with single family dwellings lay outside this area. Individual houses were about 12 x 16 feet while the main lodge (meetings, worship, protection) was about 20 by 60 feet.

Family gardens were tended beside each dwelling and were from 100 to 200 feet square. The Captain noted that “they look cleaner than our English gardens.” Garden guards were keeping watch night and day in July to keep out marauding rabbits, groundhogs, raccoons, and deer. The list of plants observed in these gardens included peas, pumpkin, (green) squash, beans, sunflowers, gourds, corn and tobacco, most of which are still mainstays of Tidewater gardens.

There was also a “communal garden” which Smith reported grew mainly corn and tobacco. He estimated this to be twenty acres in size and cultivated mainly to pay the tribal tribute to Chief Powhatan who demanded 8 to 10 parts of everything growing there.

The Massawtec “extended every hospitality” to Smith and his party but the party decided not to “lay down for the night” in the village but in the boats anchored in the middle of the river with shields in place. Sure enough during the night the shields were hit by several volleys of arrows which did not penetrate. Mosco declared they had been shot by the same Manahoc war party which had attacked several nights earlier. The next morning the expedition headed back down the Rappahannock.

His travels through hundreds of miles of waterways in Tidewater, Virginia led Captain John Smith to write his observation, “Heaven and earth never agreed better to frame a place for man’s being, were it fully manured and inhabited by industrious people.” Most of us presently living in Tidewater, Virginia now feel that this can be as truly said in the present time as in 1608.

This article first appeared in The Tidewater

April, 1993 Volume 2 Issue 8

Much is known of the Indians in Stafford County because of oral traditions and the writings of Captain John Smith. In 1608, he explored Aquia and Potomac Creeks from the Potomac River. He visited the Indians at Indian Point in Marlborough Point as well as exploring the Rappahannock River. Smith’s diaries are a valuable resource of information about the Patawomeck Indians in most of Stafford as well as the Manahoac Indians found west of the Fall Line into the Hartwood area.