Ferry Farm

African American History

Enslaved men, women, and children labored at Ferry Farm from the 1720s until 1862. While the farm’s written record regarding the enslaved community is sparse, research that combines archaeology and surviving documents reveals aspects of the daily lives of those who involuntarily toiled and lived at Ferry Farm.

Most of the written records derive from court proceedings that took place during the period that the Washingtons owned Ferry Farm (1738-1772). At the time of Augustine Washington’s death in 1743, his probate records 27 named enslaved people living and working at Ferry Farm. This list excludes those owned by his wife Mary Ball and does not reflect the constant movement of enslaved communities between different Washington owned properties. This makes it difficult to determine how many enslaved individuals lived and worked at Ferry Farm at a given time. In total, 57 enslaved men, women, and children, most known by name, have been connected to the property during the Washington tenure.

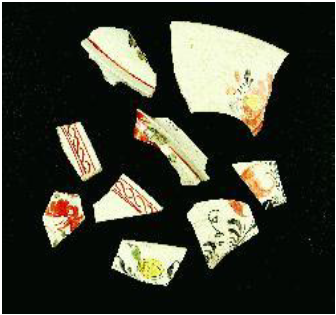

Archaeology lends itself to reconstructing the lives of those enslaved at Ferry Farm. Identification of buildings and fences reveals the layout of the plantation and, in turn, identifies the areas enslaved people lived and worked. The Quarter, located adjacent to the Washington House, likely housed a single family. The presence of wig curlers suggests that the individual tasked with maintaining the Washington wigs lived at this quarter, while outdated ceramics and other artifacts reveal the family received hand-me-downs from the Washingtons. Other artifacts found on the property reflect cooking, mending of ceramics, sewing, and field cultivation as types of labor undertaken by the enslaved community. Personal effects divulge how individuals forged identities and preserved aspects of West African culture. Instruments, such as jaw harps, provided entertainment, while colonoware, a hand-built pottery, blended English vessel forms and African manufacture techniques. Some artifacts made the Middle Passage with their owners and became part of African diaspora. Cowrie shells functioned as currency in West Africa but transitioned to self-adornment in the Americas. Carnelian beads identified high status individuals in West Africa, while imbuing their owners with spiritual powers, and the recovery of one such bead at Ferry Farm indicates that these special beads continued to play a role in the lives of enslaved individuals in colonial Virginia.

After George Washington sold Ferry Farm, it continued as a place of enslavement. The practice ended in spring of 1862 when the Army of the Potomac occupied the property. Union troops constructed a canal boat bridge that connected Ferry Farm to Fredericksburg allowing those seeking self-emancipation to use Ferry Farm as a crossing point to reach Northern lines in Stafford County.

Archaeology

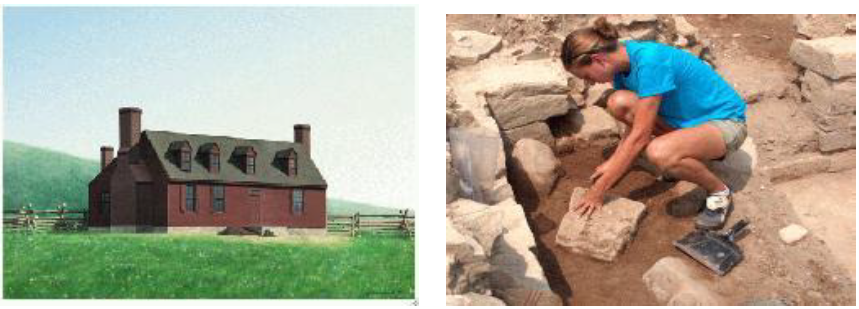

Archaeologists working at the site of George Washington’s childhood home have located and excavated the remains of the long-sought house where Washington was raised. The site was the setting of some of the best-known stories related to his youth, including tales of the cherry tree and throwing a stone across the Rappahannock River.

Digging at the Ferry Farm site near Fredericksburg, Va., the archaeologists say that evidence unearthed over seven season of excavation has positively confirmed the foundation and cellars that remain from the clapboard-covered wood structure that once housed George, his parents and siblings.

“This is it – this is the site of the house where George Washington grew up,” said David Muraca, director of archaeology for The George Washington Foundation (GWF), which owns the property. Fredericksburg lies about 50 miles south of Washington, D.C., and Ferry Farm is just across the Rappahannock River in Stafford County, Va.

Muraca, working with historical archaeologist Philip Levy, associate professor of history at the University of South Florida, found from the evidence that far from being the rustic cottage of common perception, the Washington house was a much larger one-and-a-half-story residence, perched on a bluff overlooking the Rappahannock. The evidence also shows that a fire that struck the home on Christmas Eve of 1740 apparently was small and localized. Historians had long believed that the fire had driven the family to live in out-buildings while waiting out repairs.

“If George Washington did indeed chop down a cherry tree, as generations of Americans have believed, this is where it happened,” said Levy, whose research is partly funded by National Geographic. “There is little actual documentary evidence of Washington’s formative years. What we see at this site is the best available window into the setting that nurtured the father of our country.”

Although the 113-acre National Historic Landmark site called Ferry Farm was known to have been the former home and farm of the Washington family, several attempts by others to locate the house among remains of five farms that once stood on the land had failed. In their search, the GWF archaeologists excavated two other areas on the property, uncovering remains of one house that predated the Washingtons’ home and one from the 19th century.

Most of the wood and other elements of the original Washington structure are long gone – many of them “recycled” by builders of houses later built on the property or destroyed by Civil War troops who once camped there – and part of the house foundation has eroded away. But as they dug through layers of soil, the archaeologists came upon the remains of two chimney bases, two elegantly crafted stone-lined cellars and two root cellars, where perishables once were stored.

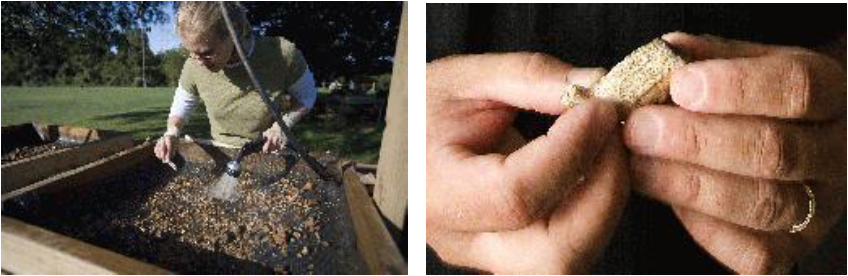

Excavation of the four cellars yielded thousands of artifacts – pieces of the house’s ceilings, painted walls and family hearth; fragments of 18th-century pottery and other ceramics; glass shards, wig curlers and toothbrush handles made of bone. The cellars constituted a time capsule of evidence that helped the archaeologists confirm that they had indeed found the long-lost residence.

* * * * *

Stafford is honored to be home for the George Washington’s Boyhood Home, Ferry Farm. George Washington moved here to Ferry Farm at the age of six, and lived here until the age of 19. Here, young George grew to manhood, developing his morals, as we know through tales of the “chopping of the cherry tree.” Though no structures remain on The Washington Family Farm site, archaeological digs are on-going to locate the foundation of the original house. Self-guided walking tours of the property are open to the public.

- Website: FerryFarm.org

- Hours of Operation: 10am-5pm (Mar.-Oct.); 10am-4pm (Nov.-Dec.)

- Admission: $5.00 Adults, $3.00 Youth (6-17). Free for kids under 6.

- Closed: Easter

Thanksgiving

24, 25, 31

Jan. & Feb. (Open on President’s Day) - Group Tours: Available any time by appointment at group rates

- Archaeological Dig Site: Open May-September

- Address: 268 King’s Highway, Fredericksburg, VA 22405

- Location: Stafford County, VA (east of Fredericksburg on State Route 3)

- Phone: (540) 370-0732

- Fax: (540) 371-3398