Falmouth

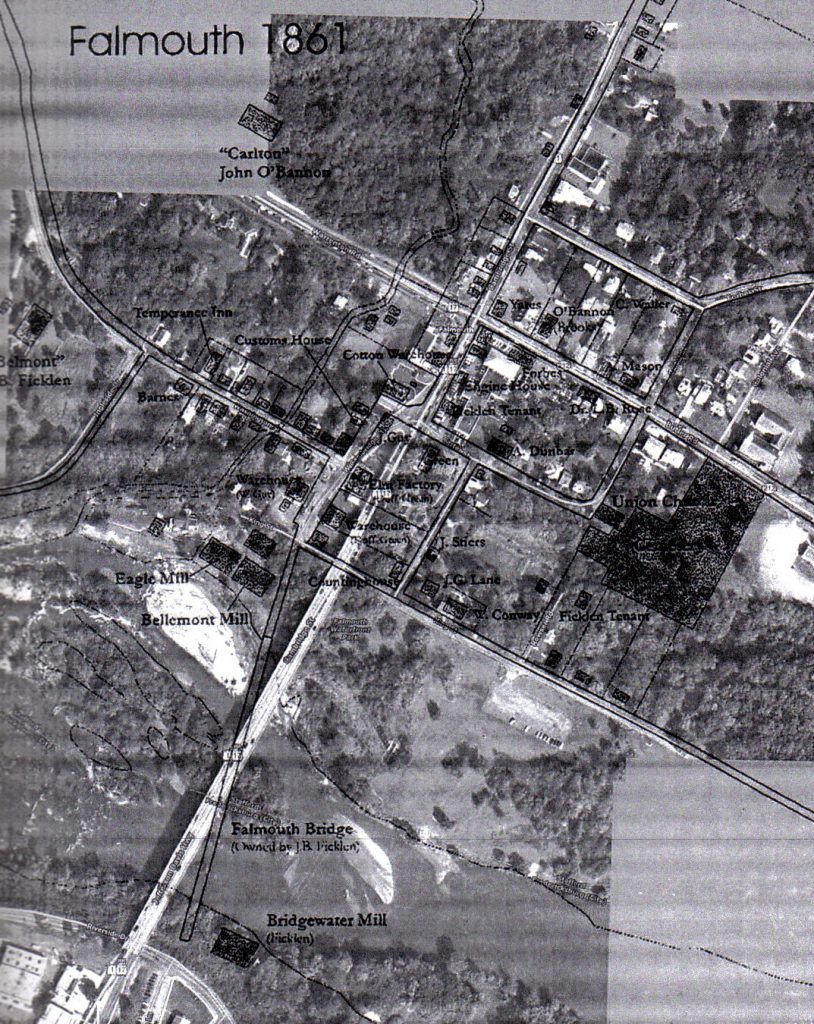

The town of Falmouth was established by act of Assembly in 1728 on land owned by William Todd (c.1685-1736) who in 1721 had built a tobacco warehouse there. Typical of these types of towns, the Assembly appointed a small group of men to act as trustees. They were responsible for selling lots and overseeing the day-to-day operations of the village.

With roads leading from Todd’s warehouse down into the Northern Neck and westward into the Shenandoah Valley, this site was an ideal place to establish a town. Falmouth is built at what was, in the early 1700s, the uppermost navigable point on the Rappahannock River. During this period, it was quite normal for towns to be established as far upstream as boats could go at low water. Farmers who lived inland from navigable water had to get their crops to wharves from which they could be shipped. Transporting goods over rough and extremely muddy roads often resulted in damage; thus, having ports placed as far upstream as possible was of great importance to those upland planters. For many years, nearly all goods and crops produced in the Shenandoah Valley passed through Falmouth en route to worldwide destinations.

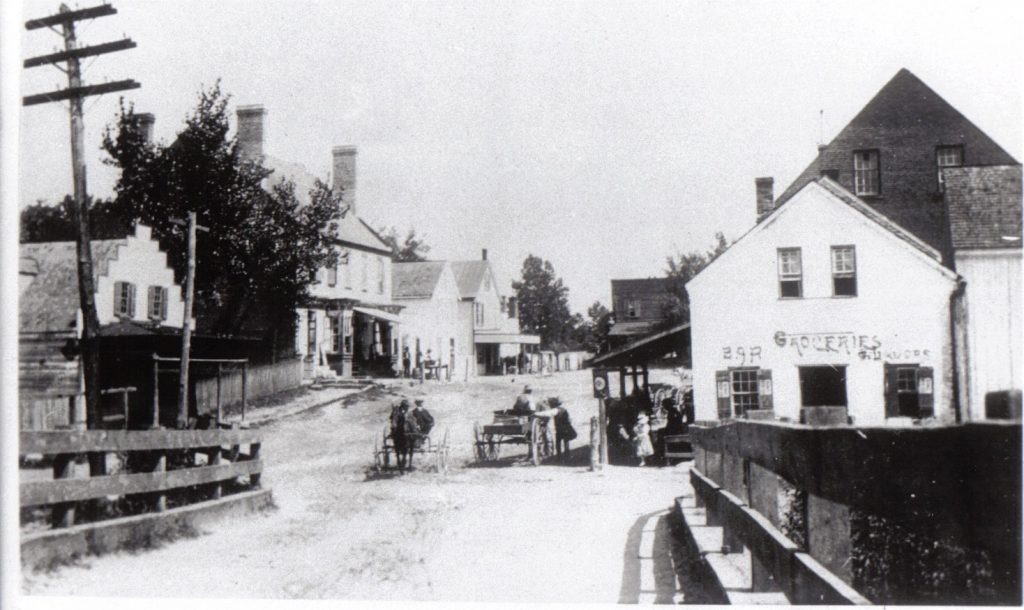

Shortly after the town was officially created, a large sandstone wharf was built just slightly downstream from what is now the Moncure Conway house. The wharf survives today but is covered by tons of sand. From this wharf ran a ferry that constantly conveyed passengers, cattle, horses, goods, and wagons between Falmouth and Fredericksburg.

Planters, captains, and ships’ crews converged at Falmouth creating opportunities for various types of other commercial activities. General merchandise stores were opened by tobacco factors who were agents for the large tobacco-buying companies in England and Scotland. The factors purchased the tobacco from the planters and sent it by sailing vessel back to Europe. These same ships returned to Falmouth with manufactured goods from Europe and rum and molasses from the islands. Carpenters came to Falmouth where they could find work repairing the ships, constructing buildings, and making barrels to hold the tobacco and the flour made at the grist mill. Stone and brick masons were needed to build and repair foundations, chimneys, and even entire buildings. Leather tanners processed leather and shoemakers used that commodity to make shoes, boots, saddles, harnesses, and other necessary items. Falmouth had a large assortment of bakers, blacksmiths, tailors, clockmakers, furniture makers, grocers, and many other types of craftspeople. Keeping everything functioning were the white, free black, and enslaved laborers.

Tobacco warehouses were usually at the heart of these 18th century towns and they played a vital role in the colonial economy. Tobacco was not only smoked, it functioned as money and maintaining a consistently high quality was essential to the overall health of the economy. The Virginia Assembly appointed official tobacco inspectors for each of the tobacco warehouses. These men were responsible for inspecting all tobacco brought to the warehouse and rejecting or disposing of any that was of inferior quality. After inspecting a planter’s crop, the inspectors issued him tobacco notes that listed the quantity of tobacco he had stored at the warehouse. These notes circulated and were used as cash amongst individuals and businesses. In Stafford official tobacco warehouses existed at Aquia, Marlborough, Cave’s (near Belle Plains on Potomac Creek), and Falmouth. During the late 1700s, Falmouth actually had two sets of tobacco warehouses. The old ones built by William Todd stood approximately where now exists the parking lot for Amy’s Café. A second set was built on or near the present site of Simpson’s Real Estate office. Most of Stafford’s tobacco warehouses had closed by 1804.

From the town’s creation until 1798 the ferry provided the only means of crossing the river from Falmouth to Fredericksburg. Built by Falmouth merchant and industrialist Robert Dunbar (c.1745-1831), this was a wooden toll bridge. Violent floods, to which the river is prone, washed out the bridge on several occasions.

Because Falmouth was built at the uppermost point of navigation, silting of the harbor was of constant concern to the trustees. By the end of the 18th century, it was no longer possible for sailing vessels to dock at Falmouth’s wharf and goods from Falmouth had to be carried by flat-bottomed scows down to ships docked at the Fredericksburg wharf where the water was deeper.

Tobacco was the heart of Falmouth’s economy until around 1800 when that industry declined and was replaced by wheat and flour. Several very large commercial flour mills were built in Falmouth and these produced many tons of flour that were consumed locally as well as being shipped to Europe. These mills were water-powered, though that power was drawn from Falls Run rather than from the Rappahannock River.

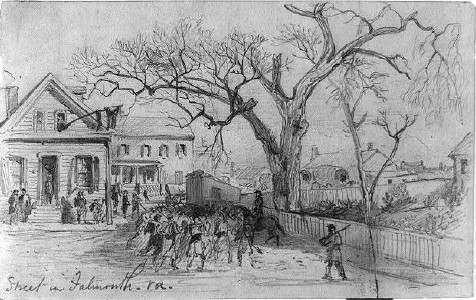

After about 1820, the flour industry declined to a great extent; but the Industrial Revolution had brought great changes to the northern states and that new technology was brought to Falmouth where several of the old flour mills were converted to textile production. From the early 1820s until 1861 Falmouth was a major producer of cotton yarns, cloth, batting, etc. The Civil War brought devastation to the countryside as well as to the Virginia economy. While one of Falmouth’s cotton mills continued in operation after the war, the economic base was gone and demand limited. After the close of the war, business resumed in Falmouth, but on a very limited scale. The Elm Cotton Factory produced sporadically for the next twenty or so years, but business in Falmouth was primarily mercantile-related.