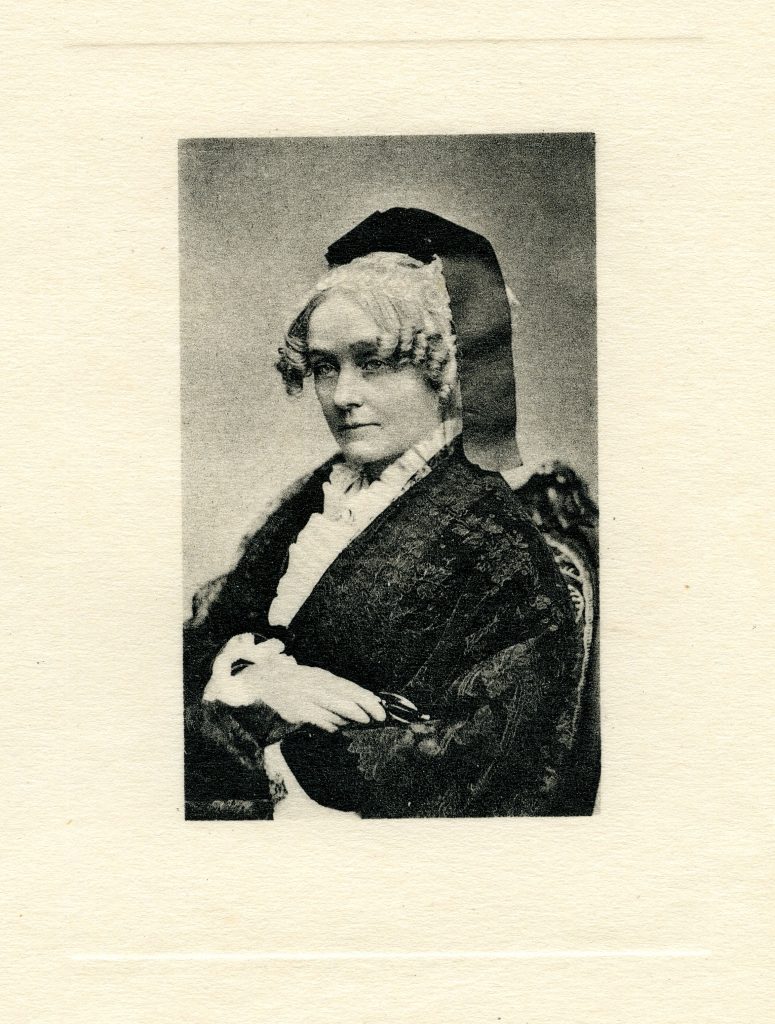

Ellen Harris

If the “cruel war” had not come and changed America forever, Ellen Harris, then 45 years of age, would probably have lived a happy matronly life in middle-class obscurity. Like so many ladies before the war, she was a member of a number of charitable groups, earnestly engaged in helping the destitute and ignorant in her community and in foreign lands. Childless, much of her life no doubt centered around church work at First Baptist Church of Philadelphia.

Once the war began, these groups flowed naturally into a ladies’ group which met and organized a system of relief for the sufferings and privations which they knew (or at least suspected) must follow in the train of war. Naturally, they were most concerned with the spiritual and material nurture of the Union soldiers. It quickly became obvious that there were extraordinary needs — both on the homefront and in battlefronts of the war. The members of the Ladies’ Aid Society of Philadelphia, of which Ellen was elected secretary, were bursting with good intentions.

They soon realized that, in order to help build and renovate hospitals and provide material assistance in the city, they would need to ally with other organizations in reaching and helping the soldiers in Virginia, the seat of war. Fortunately, during the first months of the war, two such groups came into existence which met their needs: The United States Christian Commission and the United States Sanitary Commission. The men who dominated these groups included clergymen and men of strong faith and convictions, better fitted for giving sermons and directing others. Such leadership was largely cerebral, with a minimum of physical labor or privations. If energetic and hard work were the order of the day, the bold sounding commissions need a strong force of church women and male field volunteers if there was hope to raise sufficient money in communities and manufacture or collect and distribute the “donations” intended for the army. As the war progressed, it was even clearer that there would be a need for even greater exertions and sacrifices by Union women and men.

Ellen’s war truly began on Sunday, the 21st of April, 1861, when a notice she had written as society secretary was read in her church and several others. The broadside called for a general meeting to perfect plans for establishing a hospital for the reception of the sick and wounded soldiers, and to prepare bedding, bandages, and lint. Her heart probably pounded listening to her own words, written in moments of great passion and energy, to enlist support of women and other citizens. The nearby Third Dutch Reformed Church and their pastor, Dr. Taylor, reportedly had burst forth in tears as Ellen’s words had overpowered them with a compelling desire to do something. She soon realized that human words truly mattered and they could bring forth action in others. Before a drop of blood had been shed, it was already questionable whether the people could endure a long and bloody conflict with fortitude. In any case, they were able to create that hospital; however, it unfortunately soon became apparent many more would be needed.

Ellen soon wondered whether she should and could do more herself, and become personally involved at the front of the action. No doubt, husband John must certainly have expressed concern. She was approaching 45 years of age and physical descriptions do not suggest she was robust. But, to have accomplished all that history recalls she must have had determination and heart. Scribbling broadsides on fundraising while her countrymen faced death in desolate places was not likely something she could politely side-step.

Her letters, most frequently addressed to the president of the Ladies’ Aid Society, Mrs. Joel Jones, at 625 Walnut Street. In them, she related personal accounts of the wounded soldiers and their daily struggles and terrors. One wounded boy of 18 at the oldest, Harris wrote, was told: “Let me be your mother and try to comfort you.” She noted, “He implored me to write to his mother a very long letter, sending a piece of his hair.” She added that that she “could fill page after page with just such histories, and many more touching.” In 1862, Ellen Harris, secretary of the Philadelphia Ladies’ Aid Society, left her home to volunteer at hospitals at the front. In doing so, she wondered “how many thousands have died for want of prompt and efficient help.” The letters – reports really – she forwarded to society members would form an enduring record.

Letter regarding Fredericksburg Campaign

During the period after October, 1862, specifically in December, a great battle took place in Virginia, and I continued my hospital labors. After we moved back into Virginia, the battle of Fredericksburg took place and it was as grisly and devastating as Antietam had been. All along the Rappahannock River, we faced the results of the deadly struggle across the river. I heard that over 9,000 men had been wounded. The thousand ambulances of the army brought back the wounded to our side over rickety floating bridges which groaned under the weight of the wagons while the sounds of the horses’ hooves ricocheted in the small valley. We again did everything possible to comfort the men and alleviate their physical and spiritual suffering. It took us until Christmas to clear the wounded from the hospitals and send them on their way to Washington or to camps within the battlefield. Our gallant General Burnside had suffered a savage loss in the battle. Within weeks of Fredericksburg, however, it was clear even to us civilians that another attempt was to be made. The army marched off in mid-January and we waited with horrid anticipation for the next large flow of wounded men from the next battle. The weather took a noticeable shift, warmed and rained in deluges I had not before witnessed in that part of the country. Soon the regiments began returning. When we asked what had happened, we were told that the area to our west had become inundated with rain and the movement of the army had chewed up the ground so that it had become stuck hopelessly and could not even cross the river. Our poor men, how sad and demoralized they were and how tired and beaten! Within a few days all had returned to their camps. I had not seen the soldiers this sad and listless before; and I hope never to see them in such a state again. They were disheartened, perhaps utterly demoralized at that dreadful point in the war. We heard reports of their desertions rising to 200 a day. Provost marshal patrols were everywhere checking every soldier. Writing in December of 1862, I expressed my heartfelt thoughts:

I am at present exercised in mind and body to a fearful degree. Think of the cold weather of the past week, and of hundreds of our boys, many of whom we had nursed at Bolivar and Smoketown, who came here to join their regiments, being thrown into this camp to suffer and die. So it has been. Fifteen of those in whom I was interested have died–shall I write it? — of starvation and exposure, within three weeks, and that under the shadow of our Capitol.

Letter regarding Union Army’s “Valley Forge,” Stafford County, Virginia

Nothing less than unabated zeal and devotion were needed on the part of our medical staff and many helpers. It seemed that death stalked the camps of our army. At no time in the long struggle was our sanitary service more needed. I clearly recall the winter of 1862-1863 because it struck me and many others that this period was so like that winter of 1777-1778, in which our brave Continental army under General Washington suffered at Valley Forge near my Philadelphia home. Our troops had been worn down by the unexampled fatigues their fall campaigning and, when the cold, wet, ever changeable weather set in, sickness multiplied at a rate so alarming, as to threaten the very organization of the army.

I am told that General Washington grew to manhood here on this very shore of the Rappahannock. How it must pain his soul to witness from heaven this terrible war among his grandchildren – once so firm in union, and now struggling to kill another with such abandon that it makes my heart sink and my soul cry out in pain.

Between 30,000 to 40,000 men are in the sick and convalescent camps that extend from the Rappahannock to the Potomac. Another 30,000 lay in the military hospitals in and around Washington. Last November, I engaged in letter writing to our governmental leaders in Washington to direct their attention to the destitution and suffering in these convalescent camps; these resulted, I am somewhat happy to add in some slow and inadequate remedies applied poorly.

I was pleased that, in January, the command of the army passed into the hands of General Hooker, and it seemed to me that the army was, over the next few months and by degrees, in a better spirit which soon seemed to have been infused into the whole Union force. There was so much suffering during the winter from cold and sickness. Picket duty in all sorts of miserable weather was very heavy burden on the men of the army and the sick were at all times abundant. For many weeks I have been established at the Lacy House, where my self-imposed duties have been both onerous and varied. Yet, at the same time, I feel as if I were making greater contributions than ever before because here I can help the living as well as the sick and dying. I’ve learned the message Mr. Stuart of the Christian Commission uttered to us so long ago – over a year – that there’s as much Christian love in a clean shirt or a warm meal as in a prayer. I took that message to heart. I procured a stove, some corn-meal and ground ginger, and with wine and crackers prepared, every day, and often twice in a day, a large supply of “hot ginger panada” for the pickets as they came in from the line of the Rappahannock. The boys were extremely fond of this preparation, and were drawn up in line in front of my “head quarters,” each receiving in his tin cup, from my own hands often, the wholesome and stimulating preparation. How many poor fellows, coming in from their cold and solemn posts, where they had stood for long weary hours for three days’ running, received these foods, I do not know. But I like to think that many of them, suffering as they were from the weary hours of an inclement night in the mud and sleet of the Virginia winter, were saved from pneumonia by this simple expedient.