Mills

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and even into the early twentieth century, grist mills were centers of social life where nearly everyone gathered to do business, share information, and visit. Bellfair Mills was for many years the hub of the northern Stafford community that surrounded it, functioning as a mill, post office, store, meeting center, polling place, and unofficial school board office. Bellfair stood on the south side of the middle prong of Chappawamsic Run on land that is now part of the Quantico Marine Corps reservation.

The choice of a building site for a mill was determined by the nearby geography and the water source that would power it. Ideally, the area upstream from the intended mill was slightly hilly, had a strong flowing run passing through it, and had a relatively narrow valley or other low spot that could be dammed to create an impoundment area generally called a mill pond. Water was not usually routed to a mill directly from the flowing stream as it was difficult to control it during freshets (floods). Floodwaters cascading over the mill wheel could destroy both it and the building. In all but the worst floods, an impoundment area allowed the miller to control when and how much water came to his mill.

Beyond their obvious use as a place to grind wheat and corn, some mills were fitted to perform other tasks that could be accomplished with water power. In rural communities, most families grew their own grain, which required grinding into flour or meal. Nearly everyone needed sawed lumber for building purposes and a number of Stafford mills were outfitted with water-powered saws. Like Bellfair, Fristoe’s Mill, a small early nineteenth century operation about a mile and a half from Bellfair, performed both of these functions, but it was also capable of “fulling” or processing home-spun woolen cloth into usable fabric for making clothes.

Millers often capitalized on the steady flow of customers to their buildings by expanding their services to include amenities such as a post office and a dry goods store. These stores often sold a wide range of essential goods, including popular medications, making them the Wal-Marts of their day. A post office was established at Bellfair Mills in 1848 and it was still operating in 1895, though it may not have functioned continually throughout that time. Little else is known about the post office there.

Exactly when the first mill was built on this site isn’t known, but the run’s dependable water flow powered several mills in the northern part of the county. Presumably, a mill was standing on the Bellfair site by at least 1809 when a deed mentions the mill dam. Around 1816 Benjamin Tolson (1763-1838) and William Gaines (1754-1819) purchased the mill and ran it in partnership for about three years. Tolson and another partner had purchased the previously-mentioned Fristoe’s Mill in 1810 and Tolson was involved with both operations until his death. During Tolson’s ownership, the land tax records listed Bellfair as the “Large Mill” and Fristoe’s as the “Small Mill.”

Building assessments were not included in a separate column in the land tax records until 1817 at which time Bellfair Mill was valued at $3,000, a considerable sum. Improvements in the facility increased the following year’s assessment to $3,600. Unfortunately, with the exception of the land tax records, no documents are known to survive that reveal the extent of activities there.

Tolson died in 1838, but his heirs continued operating both mills and it took nearly ten years to completely settle his estate. Finally, a law suit forced the sale of Tolson’s extensive land holdings in northern Stafford. An advertisement in the Alexandria Gazette newspaper of Dec. 17, 1846 provides a brief description of Bellfair. This reads, “Bellfair Mills Tract, contains 90 acres. It lies on the middle branch of Chappawamsic run, about 6 miles from tide water. It has on it a large Grist Mill with a sixteen feet overshot wheel, and never failing stream of water. The mill house is large, well built of stone and may be easily fitted up with Machinery for manufacturing purposes. It is also a very good stand for a Store, and one room in the mill has been used for that purpose.”

William Carter (c.1804-1874), James E. Tolson (1795-c.1867), and John Clark (1804-1882) bought the mill and 90 acres from the sale of Tolson’s estate, paying $1,100. Clark was a millwright, bridge builder, and a Baptist preacher. These men seem to have operated the mill until the Civil War brought activities there to a halt.

The mill survived the Union occupation, but was in very poor condition after the war. The land tax records suggest that it suffered not from vandalism typical of war-ravaged Stafford, but from long-term heavy use and years of neglect. Surviving in the Stafford County court records are several carefully itemized receipts from 1865 for repairs that John Clark made to the mill. He subcontracted some of the work, payment for which was in “Yankee money.” The mill was assessed at $1,000 in 1869 and by 1876 the value had increased to $2,000.

Mills were popular meeting places. In 1877 the “Mutual Aid and Improvement Society” met at Bellfair. A 1909 newspaper notice announced, “A picnic will be given at Bellfair Mills on Saturday, Aug. 7, commencing at 8 a. m. A tournament will be held, the prize being an English saddle and bridle and a pair of spurs. Four handsome crowns will be given to the queen and three maids of honor. Ice cream, confectioneries, soft drinks, dinner, &c. A band of music for dancing. A real day of enjoyment will be afforded all who come.”

George M. Weedon (1840-1902) opened a store at Bellfair around 1870 and operated it until being appointed Stafford’s first Superintendent of Schools in 1885. After assuming that important position, Mr. Weedon accepted job applications at Bellfair and conducted job interviews there with potential teachers.

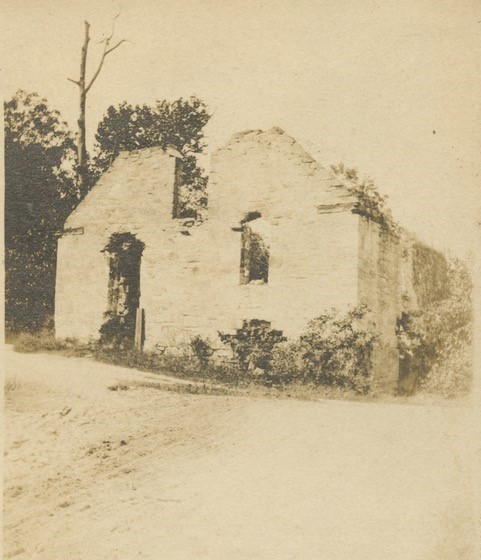

A post-war description of the building states that Bellfair was a three-story building, the lower two stories constructed of stone and the uppermost story of frame. The top floor was used as a store and post office. The lower level contained the mill machinery and the middle floor housed the millstones where wheat and corn were ground into flour and meal. This was a typical arrangement for this type of facility. Operation of the mill from the late nineteenth century onward seems to have been sporadic. Exactly when Bellfair ceased functioning isn’t known. Presumably, it quietly deteriorated and was never restored.

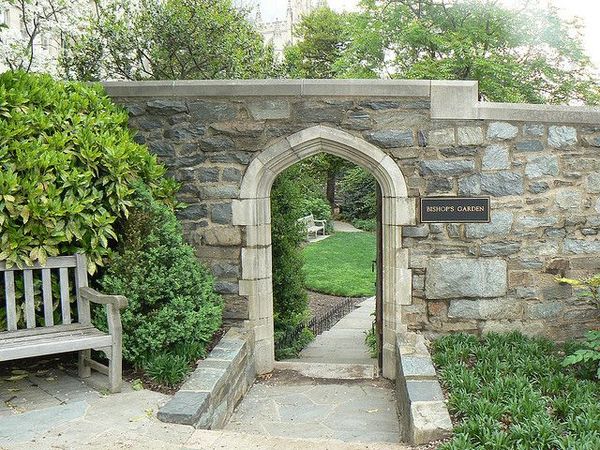

Brooke’s Mill, Brent’s Mill, and Ravenswood Mill were all built of Aquia freestone. Around 1929, these were dismantled and the stone sold to the builders of the National Cathedral. It can still be seen in the Bishop’s Garden there where it was utilized in the construction of walls, a gazebo, and other garden features.

The mills left because the technology and transportation had improved the way people got their flour and meal. Earlier, grist mills were scattered throughout the county and they ground the wheat and corn brought there by local farmers. Nearly all of them were water-powered, which could be challenging since operating the mill was dependent upon adequate water flow – no water, no grinding. Some of these buildings were also fitted out to saw lumber, the issue with water availability impacting that operation, too. By the early 20th century, some mills had converted from water power to gas or Diesel engines to run the equipment. Some people complained about that because they said that the flour and/or meal tasted like exhaust. In the meantime, large merchant mills, which bought and ground grain by the ton, were increasing in number. Some of them were powered by water and some by steam, but they produced large quantities of what was called “product,” a term for flour or meal. The roads were improving, which made transportation easier, the old local water-driven mills couldn’t compete with the big merchant mills, and it was simply easier for a person to buy a sack of flour from one of the multitudes of country stores then existing. Maintaining a water-powered mill was also costly and they had a bad habit of being washed out in floods or catching fire.

Brent’s Mill burned around 1900 leaving nothing but the shell. It simply wasn’t worth rebuilding. The image of Brooke’s Mill that was used on a c.1909 postcard shows the building abandoned. We know almost nothing about the Ravenswood Mill other than it existed. Towson’s Mill, which used to stand in the big bend on Coal Landing Road, disappeared at about the same time as the other three. From what we can tell, that building saw little to no use after the Civil War. We don’t know with certainty that the Cathedral got that stone, as well, but we’re guessing that it did.

Photos of Brent’s mill, maybe taken in the 1890s or so and one taken around 1901 after the fire.