Falmouth Bridge

Thousands of people drive over the Falmouth Bridge every day without giving it any thought. Few realize that the present structure is at least the twelfth to have spanned the Rappahannock River at this location.

From the establishment of the town of Falmouth in 1728 until the first bridge was opened around 1798, people crossed the Rappahannock by ferry. Several of these were established at various points between the Stafford shore and Fredericksburg and some operated concurrently over the years. In fact, ferries continued in operation from Falmouth until the 1890s.

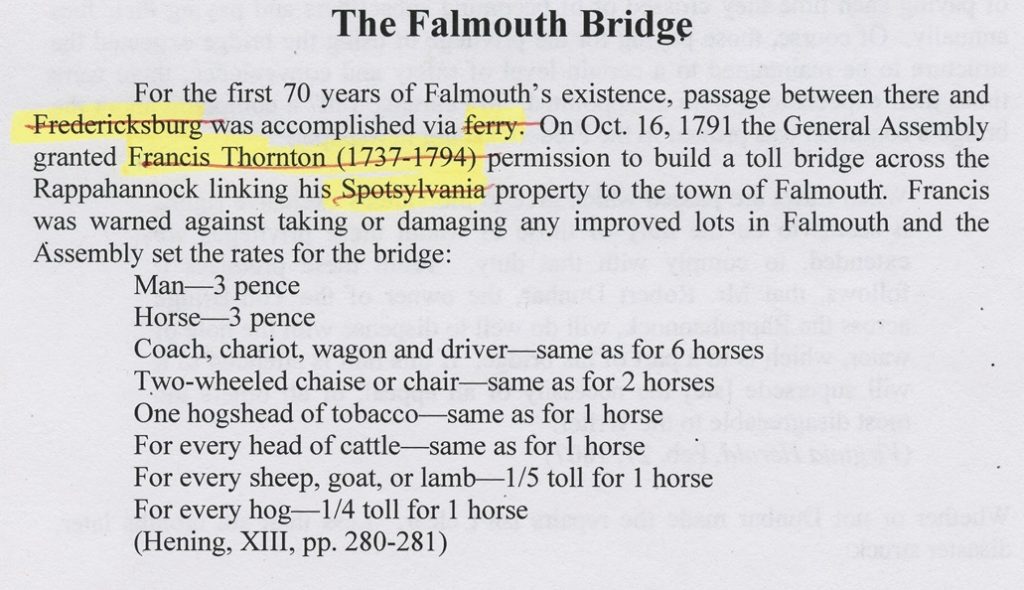

The first bridge at Falmouth was built and owned by Robert Dunbar. It crossed the river at the bottom of Cambridge Street just south of modern Amy’s Café and was a wooden structure on stone piers. It stood next to Falmouth’s first wharf. The land on which the bridge abutted on both sides of the river belonged to the Thornton family of The Falls, later Fall Hill. As part of the deal between Dunbar and Francis Thornton, in return for permission to build the bridge, Dunbar agreed to pay to Thornton and his heirs an annuity of £500 forever after. This was an enormous sum and the annuity remained in force for nearly a century.

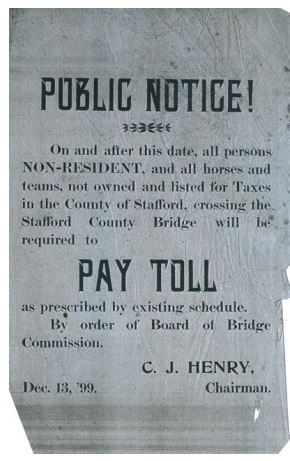

For Dunbar, building the bridge wasn’t a selfless act for the betterment of his community; it was a business venture that he hoped would turn a profit despite the very considerable expense involved. Those wishing to use the bridge paid a toll. Tolls were charged for people, cattle, horses, sheep, and wheeled vehicles. Dunbar’s bridge washed out twice during his ownership, in 1808 and again in 1826. He rebuilt it at his own expense.

In 1847 Joseph B. Ficklen purchased the Falmouth bridge from Dunbar’s heirs, still subject to the Thornton annuity. Like Robert Dunbar, Ficklen collected tolls from those who used the bridge.

Part of the bridge gave way in July 1856 “and precipitated into the river and on the rocks below, a fine team of oxen, and a wagon loaded with Wheat … Two of the oxen had to be butchered—the rest were slightly injured and the driver escaped with a few bruises.” Ficklen repaired the bridge at his own expense.

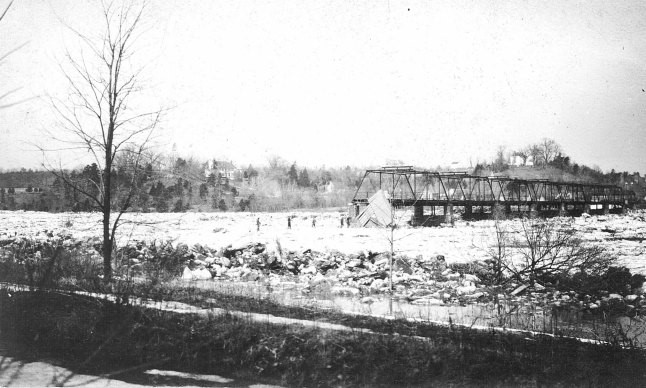

The Rappahannock River has always been prone to violent flooding, which often destroyed or seriously damaged the bridges built at Falmouth and Chatham.

In April 1861 the local newspaper reported, “The heavy and continuous rain of the past few days resulted in a tremendous freshet in the Rappahannock River, the like of which has not been known since 1814. On Wednesday morning, the swollen, turbid mass of water, increasing rapidly in height and volume, raged onward with such force as to sweep away panel after panel of the Falmouth Bridge, which with similar velocity, borne down by the impetuous current, struck the Chatham Bridge … and carried off about one-third of that structure … In a few hours the whole of Falmouth Bridge had disappeared, and from bank to bank surged the restless tide of waters.”

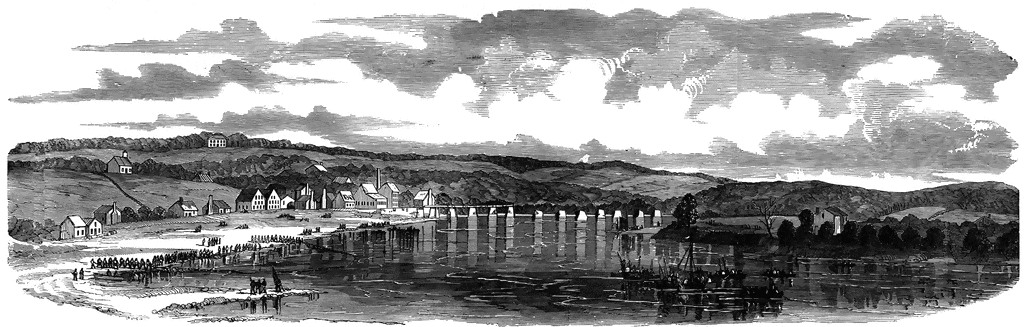

In 1929 Sarah Anderson recalled standing on the hill at her home, Pine Grove, in April 1861 and watching the flood (Woodmont Nursing Home now stands on or very near the Pine Grove house site). Sarah wrote, “I watched from that hill Falmouth’s bridge come floating down the river and hit the Chatham bridge [sic] and knock more than half of it off the pillars. Then both bridges came on down the river & hit the car [railroad] bridge which was too high out of the water for them to pull it down. The bridge was quickly rebuilt, only to be burned in April 1862 when Confederate forces withdrew from Fredericksburg. A year later I saw all those bridges and all the vessels at the wharfs all burning at once to keep the Yankees out of Fredericksburg.” Union soldiers used pontoon bridges to cross the river during their occupation.

There was no bridge at Falmouth from 1862 until the summer of 1866 when Joseph B. Ficklen arranged “for the building of his stone piers on the Falmouth bridge, the woodwork of which will also soon be contracted for.” The work was quickly completed and, in direct competition to the owner of the Chatham Bridge, Ficklen reduced the toll on his bridge to nearly the same rate as before the war “or just one half that has been charged by the Chatham bridge.”

Ficklen died in 1874 and the bridge, then valued at the considerable sum of $12,000, passed to his wife and children. The Thornton annuity passed with it.

For a number of years people had been discussing the advisability of having a free bridge connecting Falmouth and Fredericksburg. Of course, that required the use of public funds, i.e. taxes, to build a bridge and maintain it, which certainly didn’t suit those Stafford residents who anticipated using it infrequently, if at all.

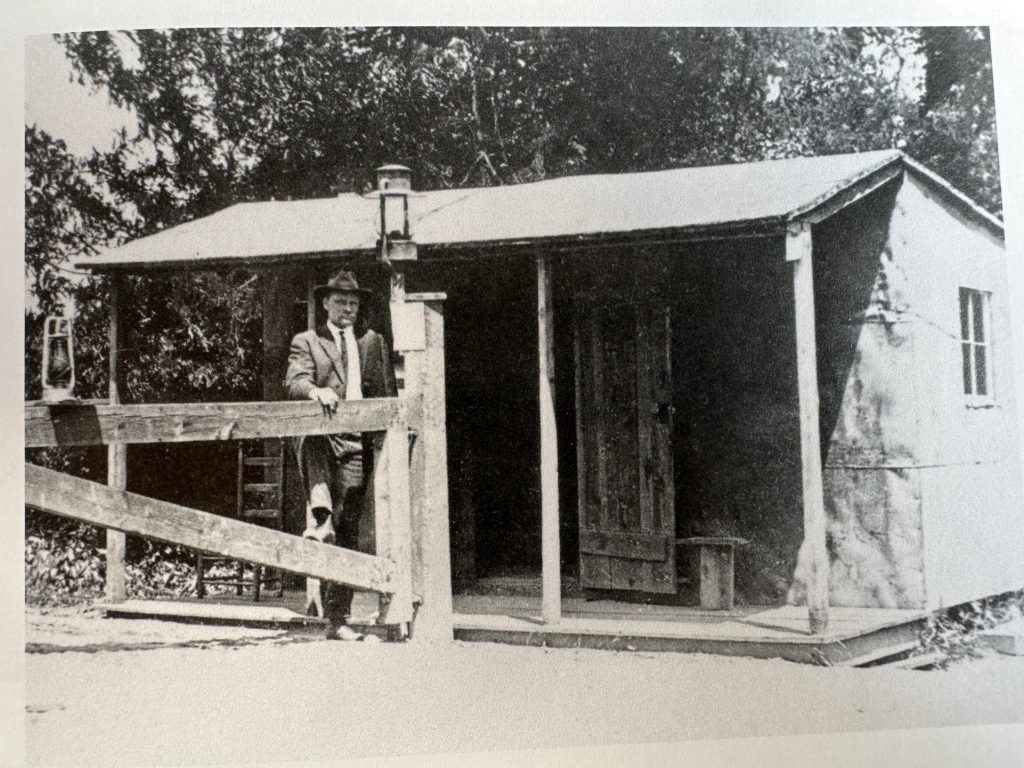

In February 1882 the Virginia General Assembly passed the “Free Bridge Act” in which the Stafford Board of Supervisors was authorized to borrow money to build a bridge across the Rappahannock. The projected cost was $24,150 for a new structure to replace Ficklen’s bridge, which was still standing and functional. A board of commissioners, one from each of Stafford’s four districts, was established and tasked with building, maintaining, and operating the bridge. They contracted with the Wrought Iron Bridge Company of Canton, Ohio to build the structure, but the project stalled.

In March 1886 the commissioners agreed with the Ficklen family to purchase the existing bridge with its toll house and lot as well as the 64-acre Amaret farm on the Spotsylvania side and upon which the bridge abutted. The bridge was still subject to a $1,666.66 annual annuity due Francis Thornton’s heirs. The commissioners agreed to pay the Ficklens $1,000 twice each year “forever” with Stafford residents being taxed to raise this sum. Stafford residents whose names were included on the tax rolls were entitled to cross the bridge free of charge. All others paid tolls.

In the fall of 1889 Fredericksburg decided to take over the Chatham Bridge, previously a toll bridge, and make it free. Thus, Stafford assumed financial responsibility for both the Falmouth Bridge and for Fredericksburg with the one at Chatham.

Shortly after purchasing Ficklen’s bridge, the commissioners decided to build a new one anyway. The newspaper reported, “The bridge promises to be a magnificent structure when completed. It will stand for ages as a monument of the wisdom of its friends, and a rebuke to its enemies, past and present…’Rah for the free bridge, for Stafford, her people, her old hares, herrings, persimmons, and her Republicans. We will also include her Democrats, with one or two exceptions.”

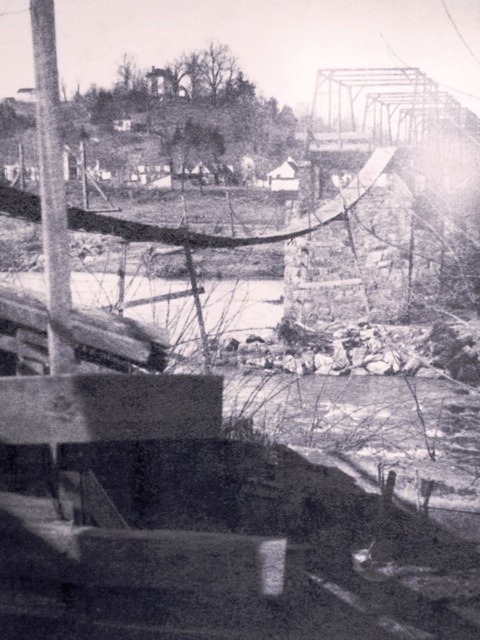

Just 29 months after this was written, a flood swept away the entire structure. It was rebuilt in 1893, but lasted only until 1918 when ice floes carried off panels from both ends. A middle section was all that remained standing. Stafford County sold bonds to raise money to rebuild.

In April 1922 the Virginia State Highway Commissioner brought suit to have the Falmouth Bridge condemned so it could be added to the new state road system. The Richmond to Washington Highway was then under construction and the Falmouth Bridge was to be included. The purpose of the suit was to determine the damages due those who still retained a financial interest in the bridge. It was at this point that the Thornton annuity ceased and the Ficklen family was paid off.

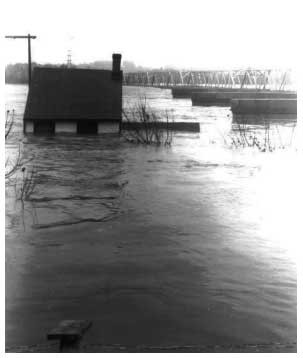

The bridge was severely damaged by flooding in 1937. For several years a narrow swinging footbridge connected the Falmouth side of the river with what remained of the bridge. Many Falmouth residents worked in Fredericksburg and having a means of crossing the river was a necessity. The only other option was to walk down River Road and use the Chatham Bridge. Construction of a new bridge finally commenced in 1942. In November of that year one of the worst floods of the river’s recorded history sent water over the top of the deck of what remained of the previous bridge and effortlessly twisted the steel superstructure.

At that point, all that had been completed of the new bridge was the pouring of the concrete piers. The flood waters actually submerged these and, after the water subsided and work resumed on the new bridge, engineers added another five feet of concrete to the tops of the piers to provide extra height. These may be viewed from beneath the current bridge. Raising the height of the bridge deck required realigning and raising Route 1 as it approached the bridge, thus accounting for the present configuration.