Fisheries

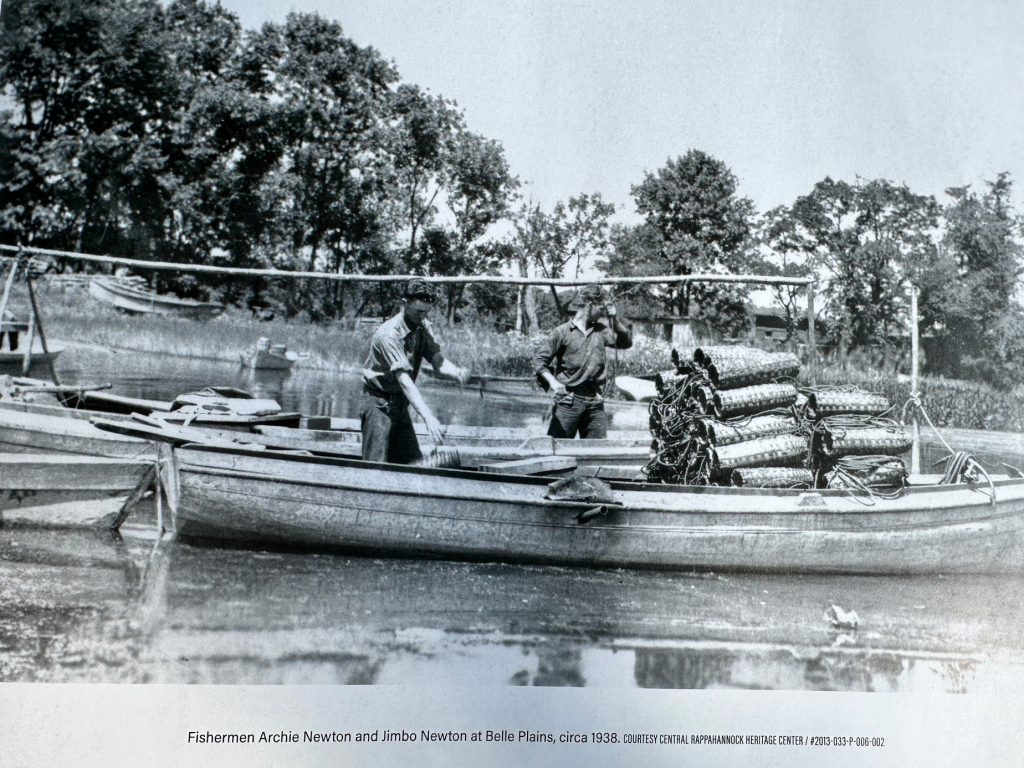

Fishing, farming, and hunting were the primary means by which people supported themselves in early Stafford. There were no grocery stores and people had to provide for their own needs and those of their families. Nearly everyone who owned waterfront property set out nets to catch fish. These fishing operations might be small, i.e., they provided only for the landowner’s needs, or much larger commercial operations.

Courtesy Central Rappahannock Heritage Center.

The Clifton Fishery in Widewater was not only Stafford’s largest such business, it was one of the largest fisheries on the east coast. Fishing here likely commenced shortly after the property was acquired by the Brent family in the 1650s and seems to have continued until the early 1900s. Most of the fish caught here were herrings, though rockfish and shad were also caught and used.

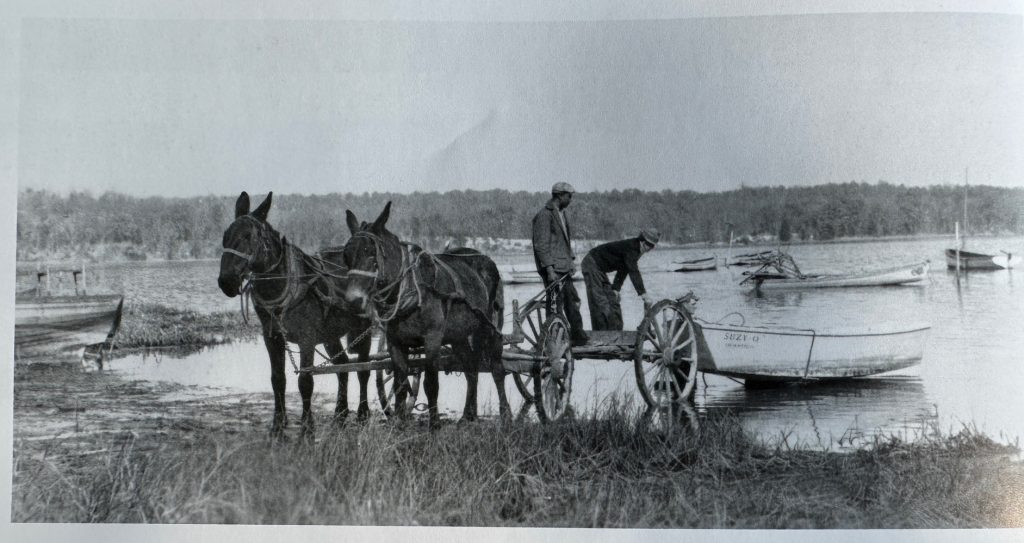

The Clifton Fishery was at its peak under the ownership of Col. Withers Waller (1825-1900) who inherited the Clifton farm and fishery from his father, Withers Waller (1785-1827). From the mid-19th century until around 1903 this was a major commercial fishery that supplied fish to local consumers as well as to people from as far away as Fauquier County. Fishing was conducted during the early spring and it was not unusual for dozens of horse-drawn wagons to be lined up along the road into Clifton. They often spent the night in line, waiting for their turn to pick up their barrels of salt fish.

Fishing was conducted using a very long net, or seine. The Clifton net was five miles in length and was laid on the back of a very large open boat. This net boat remained close to the shore while another boat, manned with about a dozen men, took the free end of the net and rowed out into the Potomac River. They dragged the net out, forming a circle, and brought the end back to the shore. The net was about 25 feet at its widest and narrowed to about 12 feet. Along the top were placed large corks and the bottom edge had lead weights to hold it down. Once the net was set, ropes on either end were fastened to capstans spaced about a half-mile apart on the beach. Mules or horses began walking around and around, drawing the net closer to shore. Often times there were so many fish in the net that it was impossible to pull it completely to shore. Men waded out into the river, pulling rowboats in which stood wooden barrels. They dipped the fish from the netted enclosure into the boats where other men were waiting to clean them and put them in the barrels. In a normal 24-hour period the net would be set twice. During the 1903 fishing season, over a million fish were harvested at Clifton.

Once scaled and cleaned, the fish were placed between layers of salt and packed in very large wooden barrels. There was no refrigeration and fish packed in this way would last for years. Many people came to fishery once each year and bought all the fish their families would consume during the next twelve months.

In the 1850s the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad came through Stafford and ran right through the Clifton Fishery. This enabled Withers Waller to expand his business even further as he could have fish in Fredericksburg or Washington, DC within a couple of hours of their being caught.

The fishery shut down during the Civil War, but resumed shortly thereafter. Because of the railroad, Waller was able to send his fish to distant markets in the mid-west and New England. After Col. Waller’s death in 1900, his widow, Anne Eliza (Stribling) Waller and her daughters operated the fishery. This continued until Mrs. Waller’s death in 1903 at which point the business was leased to other parties.

There were other commercial fisheries in Stafford County, though not as large as that run at Clifton. On the Potomac River were fisheries at Richland in Widewater, Split Rock near Marlborough Point and Marlborough. On Aquia Creek was Myrtle Grove, also in Widewater. Fishing was conducted at several points along Potomac Creek and, during the 19th and early 20th century, a large fishery was conducted at what is now a sand beach at Falmouth.

“Big Run of Herring. George W. Payne Catches 4500 Wednesday Night. Fish are certainly running in the Rappahannock at Falmouth. Mr. George W. Payne threw in his nets Wednesday morning and at two hauls caught 700 herring. Wednesday night he caught 4500 more. They are very fine, a large proportion being roe herring. His wagons were selling them on the street Thursday at 60¢ per dozen” (Fredericksburg Daily Star, Mar. 7, 1918).

The following day the newspaper announced,

“Falmouth Catch of Herring. Most Successful in History of Shore. Mr. George W. Payne caught 4,300 herring in his nets at Falmouth on Thursday night. The fishing of the past three days at Falmouth has been the most successful in the history of the shore. There have been over 10,000 herring caught. Herring were retailing Friday at 40 cents per dozen. In lots of 100 or more $3 per hundred. It is said the cause of the big run of herrings at this point is due to the ice destroying the traps in the lower Rappahannock and the fish got by” (Fredericksburg Daily Star, Mar. 8, 1918).