Aquia Train Robbery

This account has been compiled from the Free Lance newspaper of Fredericksburg, Virginia, October 16, 1894, through September 27, 1895, by Robert A. Hodge.

Charles Jasper Searcey was born in Palopinto County, Texas, December 12, 1858. He grew into a tall, slender, wiry man with well-developed shoulders, deep-set dark eyes, a low but pleasant voice, and exhibited good manners. By the age of 36, he was well-read, had traveled extensively over the Western United States and through Central and South America where he worked at his trade of carpentry. He was a Mason, a Knight Templar and a Knight of Pythias.

In September 1894, he traveled to Washington, D.C. to attend an Encampment of the Knights of Pythias and while there met a past acquaintance, Charles Augustus Morgan, alias Charles A. Morganfield. Morganfield was twenty-seven years old, a professional gambler, short, stocky, surly – in fact, essentially all that Searcey was not. He claimed to be from Neelyville, Missouri. Both men were married, but neither was accompanied by his wife. Morganfield was the father of one child; Searcey had two children.

They took rooms at the lodging house of William Miller and Thomas Willow’s on Pennsylvania Avenue near Hancock’s Restaurant where they registered under the names C.T. Vivian and C. Arlington. Being broke, Morgan suggested they plan a train robbery to better their financial position. Morgan gave what money he had to Searcey who purchased a stick of dynamite in Georgetown. Searcey then pawned his watch and used the money to purchase a pistol.

About October 7th they took a train to Fredericksburg, Virginia, on the way selecting the isolated area near Aquia Creek as the point of their intended crime.

When they got near Fredericksburg, they camped out of town at a place called Bernard’s Flats. Having no money when they came into town, Searcey asked contractor George W. Wroten for a job as a carpenter but was told by Mr. Wroten that the town was full of carpenters and that no help was needed. Searcey then begged for a quarter and Mr. Wroten obliged them. The men then crossed the street to the eating house of George E. Cole where they ordered bread and coffee for which they paid ten cents.

On Friday afternoon, October 12th, the two men left Fredericksburg and walked up the railroad to Brooke Station. They hid behind a car standing near the Alart and McGuire pickle factory. Shortly after nine that evening, they jumped on the tender of the northbound train when it stopped at Brooke Station.

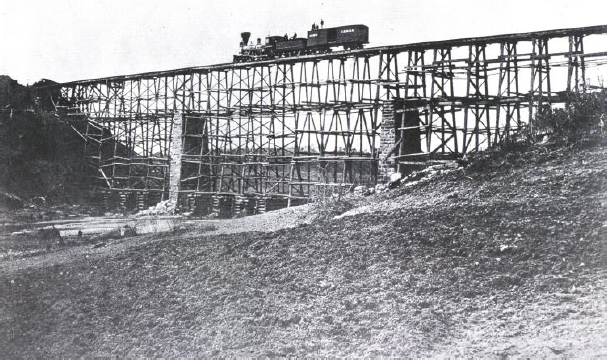

After leaving Brooke, the train stopped, at 9:27, at the south end of the drawbridge at Aquia Creek, then proceeded across it. It was just after crossing that Engineer Frank Gallagher increased speed and was looking straight ahead when the fireman, William Washington, looked up and saw the two men climb over the tender and exclaimed: “Lord have mercy.” The engineer turned and saw the men pointing pistols at them. The shorter one, about five-ten, dressed in ordinary garb, but with a red bandana concealing the lower part of his face ordered Engineer Gallagher to “Shut off”–an order he complied with immediately.

As the train came to a halt, the taller of the two men got off and ordered the others to get down. The fireman descended first, then the engineer and finally the shorter man and in that order, they marched down the side of the train to the express car where the two trainmen were ordered to sit on the side of the sloping bank and look to the rear of the train.

Captain A.M. Birdsong, one of the oldest conductors on the road, was at the rear of the smoking car counting his tickets when the train stopped. Charley Munford, the porter, pushed past him and went out the door. Two shots were heard and Charlie came rushing back and exclaimed “Robbers!”

Conductor Birdsong went out onto the platform and saw three men. Thinking to intimidate them, he called in a loud voice, “Charlie, bring me my Winchester.” He then went into and through the car, cautioning the passengers to be calm and remain seated. He inquired if anyone had a pistol? One was produced and Captain Birdsong returned to the platform with the pistol in his hand. Moonlight at the moment allowed Engineer Gallagher to see it and he called to the conductor, identifying himself and telling him not to shoot.

Searcey then called to Birdsong to go back in or he would be shot. Birdsong, instead of going in, shouted to Gallagher to go get on his engine and start the train or he would shoot him. Since robber Searcey threatened to kill Gallagher if he moved, Gallagher pleaded with the conductor to go back into the car. Finally, he did, but stationed himself at the head of the ladies car and coolly asserted he would kill the first person who set foot on the platform!

While Birdsong, earlier, was calling for a pistol, Peter MacGregor, a grip-man who lived in Washington, was scared. He ran through the coaches ahead of the conductor and got off at the rear of the train and ran along the track to the Aquia Creek drawbridge where his brother-in-law, James T. Woodward, was the watch for the bridge draw. MacGregor told Woodward the train was being robbed and the two men shut themselves in the little bridge house and remained there all night. (MacGregor later related a slightly more courageous version of his escapade, but the end result was unchanged.)

While Searcey was busy guarding the engineer and the fireman and arguing with the conductor, Morganfield had gone to the express car in which there were two express messengers, Percy S. Crutchfield and Harry Murray. He called on the occupants to open the door. One of them did, but when told to put his up, pulled the door closed instead. Morgan shouted for him to open the door or he’d blow him and his damned car to the devil! This getting no result, he discharged the dynamite and blew the heavy oak door open. Entering the car, he ordered Crutchfield to open the safe and when it was done, he cleaned it out. Morganfield then cut a small slit in each of the seven or eight through-express pouches and extracted the several packages of money, placing them all in one leather pouch. All these activities had taken about twenty minutes.

Morganfield then came out of the express car with the pouch and the two robbers and the engineer and fireman returned to the engine where the employees were told to uncouple the engine, then prepare it for moving. Engineer Gallagher let some water into the engine while Fireman Washington threw six shovels of coal on the fire. The trainmen were then told to get off. Searcey took the throttle and the engine rolled away. After a mile or so, at the old Arkendale road, Morgan left the engine, Searcey threw the throttle wide open and jumped off.

The heavy six-wheeler dashed along the track toward Quantico, twelve miles away, at terrific speed. As it passed the little station of Widewater at fully fifty miles per hour, the operator saw the engine was wild and dashed into his office where he telegraphed Quantico to look out for it.

The operator at Quantico received the warning dispatch and ran out on the platform and saw standing there on the main track, the through Southern Express which had pulled in an hour late. The operator could not see the run-away engine but could hear the roar of the wheels in the distance and knew he could not reach the switch, several rods away, in time. Fortunately, O’Leary, the young Irish switchman at Quantico, was at his post.

The abandoned locomotive came into view, bounding along at the rate of a mile a minute, the headlight swaying from side to side like a will-o-the-wisp. O’Leary knew something was wrong and without a second to think, seized the switch bar. It shook in his hands from the vibration of the oncoming engine, but he threw the switch over and on rushed the engine–not into the waiting train, but up a steep grade into a coal dump where it crashed into a number of empty freight cars. In a moment, the engine was thrown on its side and wrecked completely. The freight cars were reduced to kindling wood. The long Atlanta Special, with her 300 passengers had been saved!

When the robbers departed on the locomotive, Captain Birdsong and Engineer Gallagher started to walk to Widewater. They were almost there when they met Engine Number Seven coming from Quantico to check on the problem. The engine hooked onto the train and took it on to Washington where it arrived at 1:17 Saturday morning, two hours and ten minutes behind schedule.

The day following the robbery, Virginia Governor O’Ferrall heard of the event and issued a proclamation offering a reward of $1000 for the arrest of the robbers.

Major Myers, President of the railroad, offered a reward for the arrest of either or both of the outlaws. The Adams Express Agency called in the Pinkerton Detectives. It was reported that an examination of the manifests of the express company indicated that there was $182,000 in the car at the time of the hold-up.

Captain Dan M. Lee, at his home Leeland on the Potomac, notified the authorities that on Friday he had noticed a trim, graceful yacht lying off his landing. Since it was missing on Saturday, he was sure the robbers had used it as their get-away means.

A number of Staffordians were confident that a man named Charles Carter, who had once resided in the area and knew every inch of ground about the robbery site; who had been one of the most skillful and cool robbers ever put in Sing Sing–from which he was at the moment an escapee, would be able to give the full facts of the robbery as soon as he was caught.

Part Two

Last Month: in September 1894, two enterprising but questionable gentlemen, Charles Jasper Searcey and Charles Augustus Morgan had a common problem: they needed money. Their solution was a train robbery at isolated Aquia Creek. They jumped on the northbound train at Brooke Station, stopped the train and cleaned out the safe. They uncoupled the engine from the train and the heavy six-wheeler dashed along the track to Quantico at terrific speed straight into the path of the Southern Express. O’Leary, the young Irish switchman at Quantico, averted the disaster by seconds. Searcey and Morgan (alias Morganfield) seemed to have made a complete escape: both the Virginia governor and the president of the railroad offered substantial rewards, the Pinkertons were called in–records indicated the robbers had made off with $182,000.

The robbers, Searcey and Morganfield, actually took the country road running to the northwest from the railroad after leaving the engine. Taking turns carrying the pouch, which weighed about fifteen pounds, they walked all night and at daylight found themselves near Catlett’s Station on the Virginia Midland Railroad where they took to the woods. After resting, they opened the pouch and divided the contents. There was $2,600 in currency, six watches, some silver spoons and forks, several purses, one pair of gold spectacles and a large number of papers. The papers were put back into the pouch and the pouch was buried.

They left the woods and went to the house of Mrs. Weaver where they obtained a late dinner. (She was a very attractive lady and when she appeared, later, at the court trial to identify the men, she was the only woman witness and was the focal point of all the spectator’s attention the entire time she was in the courtroom.)

After leaving Mrs. Weaver’s, they walked all day Sunday and Monday, arriving early in the evening of Monday at Front Royal. There they purchased new clothing from a Mr. Buxbaum. Morganfield sold his old ones to a one-legged man named Shields from Middletown. (These were later recovered and used as evidence in the trial.)

They took the train to Shenandoah Junction where they spent the night and on Tuesday, Searcey bought a ticket for Cincinnati and Morganfield bought one for Cumberland, Maryland. They arrived in Cumberland at 1:00 p.m. and took rooms at the Cumberland House where they remained until dark at which time Morganfield took Searcey’s ticket and boarded the train for Cincinnati.

It was about that time that train conductor C.P. Brown became aware of the robbery details through the news dispatches and remembered the two men who had gotten off at Cumberland. He alerted the Cumberland police and they apprehended Searcey as he was about to take the train for Gettysburg at 1 o’clock Wednesday morning. He offered no resistance and was found to have $923 in notes and $630 in silver in two woolen stockings; four silver watches and one gold one; a lot of pawn tickets and a memorandum book indicating the split of the boodle.

On Wednesday, Express messenger Crutchfield accompanied an Adams Express Agency detective to Cumberland where the items and the man were positively identified.

On Friday, October 23, Stafford’s Commonwealth attorney, W. Seymour White, instituted proceedings for the extradition of Charles J. Searcey and on Saturday night, at 10:30 Stafford’s Sheriff Charles L. Kennedy arrived in Washington with his prisoner. Searcey was taken to the Adams Express Building on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington where he remained, undergoing what the police called the “sweating process” until 8:00 Sunday night. At that time he was taken to the train depot where they boarded the Atlanta Express, taking seats in the smoking car, and started the trip to Fredericksburg. During the trip, Searcey conversed cheerfully with his guards, smoked two cigars and to all appearances, enjoyed the jouney far more than any of his companions.

Because the Stafford Jail was so isolated, county judge Charles H. Ashton issued a request that Searcey be housed in the Fredericksburg jail until the 21st of November, at which time he would be indicted.

It had been reported the prisoner would arrive in Fredericksburg on the 5:15 train and fully 600 persons congregated at the depot for a glimpse of him. The were sorely disappointed that he was not on it, but hung around until the next train rolled in. Then the excitement became intense and people fell over each other in an effort to obtain the first look at the robber.

Sheriff Kennedy quickly alighted, then the prisoner, and they entered a carriage and were driven at a rapid pace up the street and through the alley to the jail. Here there was a delay of 15 minutes for Sergeant C.W. Edrington, having met the first train, did not go to the later one, but had gone home and gone to bed. He had to be awakened and hastened to the jail to open it.

The prisoner was locked in a cell on the first floor. Early Monday morning a large crowd assembled and had to be warned there was a fine of $5.00 for talking with the prisoner in jail. Two men were arrested for talking to him through the door, but when it was found they were reporters, they were released.

Searcey had made a complete confession and had agreed to help establish the escape route as well as locate the buried pouch. Shortly after noon, in a closed carriage, the party started out across the free bridge and on to Aquia village, then via the Arkendale road to Garrisonville. Searcey did not recognize the route. As it was 8:00 and dark when they reached Garrisonville, it was decided to put up for the night at ex-Sheriff Hugh Adle’s. He was a Virginia gentleman whose doors were never closed against respectable wayfarers, though he was a little taken aback when presented to the noted train robber. He speedily recovered and invited the party in where they were presented to his two charming sisters.

Now these ladies had seldom, if ever before, been called upon to entertain such company and when they looked at Searcey they imagined battle, murder and sudden death. It was with true womanly courtesy, however, that they bade all welcome and set about preparing a most delightful supper. While dining, they were charmed by the delightful demeanor of the prisoner, and could scarcely bring themselves to believe he was the wicked man he had been reported to be.

An early start was made next morning and near Bristerburg, took the road toward Calverton. About two miles from Calverton, Searcey began to recognize the landscape and indicated they must go toward Catlett. About four miles beoynd Catlett’s Station, he recognized the house upon the hill and indicated they must follow the branch to the pine woods. After an hour’s search, Mr. Adle, who had accompanied the party, cried “Here it is” and all ran to the spot.

It was a dramatic scene. The wind bent the sighing pines; autumn leaves dropped all about, the fast falling evening cast weird shadows through the forest. An old and giant pine had been blown down, making a deep hole in the earth. At the foot of the forest giant, in this hole, was the pouch. It was recovered, the trip was made back to Calverton, the pouch was sealed and shipped to Washington and the party retired.

The next day (Wednesday, October 28), the party returned to Fredericksburg and Searcey–who had been cheerful, pleasant, conversant, uncomplaining and very impressionable to everyone–was once more lodged in jail. There, at the request of the Stafford authorities, he was photographed. He seemed quite interested in having his picture good and asked for a flower which he pinned on the lapel of his coat before the picture was taken.

Six days before, on the previous Thursday, train conductor J.T. Peters, of Parkersburg, West Virginia, heard the details of the robbery and remembered the man who had taken his train from Cumberland to Cincinnati, Ohio, on Tuesday night. He notified the Cincinnati officials who in turn recalled they had investigated a man who had been found with a broken leg at Winston Place, a suburb of Cincinnati. The man said he had fallen from a freight train he had hopped in Cumberland after a gambling bout, which accounted for the large amount of money, including $110 in silver, he had on him. He was reinvestigated and a revolver was found at the site where he was found by the tracks. he was held as a suspect.

The confession of Searcey on Sunday definitely implicated Morganfield and on Monday, while Searcey was starting out to look for the pouch, Sheriff Kennedy was at the Virginia Governor’s office obtaining extradition papers. The Sheriff reached Cincinnati on Wednesday, but returned on Saturday without Morganfield who had been determined by the physicians to be too ill to be moved. Two weeks later the Cincinnati authorities indicated the leg had gotten so bad they were afraid of blood poisoning and gangrene, and when they had withdrawn his allowance of morphine, found he became violent and attacked the nurse, guard and physician both physically and with the most vile and abusive language they had ever heard. It was thought then he ahd been an opium addict for a long time.

By the end of November, Morganfield’s wife had arranged for the celebrated firm of criminal lawyers, Shay, Jackson and Coogan of Cincinnati, to represent her husband. When interviewed by a reporter, Mr. Jackson corroborated the report that his firm did not take cases unless they were well paid and that in this case they were paid in advance by Morganfield’s friends who had come to his relief. It was Mr. Jackson’s opinion that Morganfield would never be returned to Virginia, but if he was, one of the firm would be there to defend him.

On Thursday, January 10, 1895, Sheriff Kennedy was back in Cincinnati for the court hearing on Morganfield’s extradition. The prisoner was brought into the courthouse on a cot and his faded-appearing wife sat not far from him. Mr. Shay, the defending lawyer, tried several slick legal tactics, but they failed and the Judge entered the order remanding Morganfield to the Virginia authorities.

His cot, with him on it, was placed in a large furniture wagon and driven at a rapid trot to the C. and O. depot where he was put through the window of the drawing room of a Pullman and laid on the bed. The trip to Washington and then to Fredericksburg was uneventful except that Morganfield at all times refused to facilitate his removal in any way. A crowd of some hundred persons gathered at the Quantico depot, and five hundred at Brooke, all wanting to see the robber. At Fredericksburg he was driven at once to the city jail where City Sergeant C.W. Edrington placed him Searcey’s old cell, Searcey having been moved upstairs. The two did not meet face to face until the day of Morganfield’s trial.

On Wednesday, February 20th, Morganfield, on his cot, keeping his face covered so people couldn’t see him, was placed in a baggage car and Searcey, handcuffed to a guard, sat in the smoker, and the trip was made to Stafford for the first trial.

The day was spent “haggling” over legal technicalities by Judge Charles H. Ashton, Prosecutor W. Seymour White and defending lawyers, Thomas F. Shay and William A. Little. On Thursday, the jury was chosen (Charles Chesley, John W. Chilton, John Clift, Frederick Dent, Bennett Dodd, Milton Harding, R.A. Johnson, R.M. Jones, Taylor Rollins, William H. Rollins, Robert G. Stewart, and C.A. Truslow). The testimony involved over fifty witnesses and the trial continued for a week. On Thursday, February 28, the jury was given the case, deliberated for twenty-five minutes and brought in a verdict of guilty and fixed the sentence at eighteen years in the penitentiary.

Searcey’s trial was to have been held in March but was postponed or continued pending the appeal of Morganfield. In April an 800-page file was presented with the request for the appeal. On May 2, the Virginia Court of Appeals refused to grant the case their attention and on May 7th Sheriff Charles L. Kennedy took Charles Augustus Morganfield to the Richmond Penitentiary to begin his 18-year sentence.

On May 15, Searcey was taken from Fredericksburg to Stafford Court House. He was dressed in a dark cut-away coat, light trousers, brand new straw hat and a handsome pair of $6.00 yellow tan shoes. There he was photographed by W.B. Smith, the Brooke Telegraph operator.

Without difficulty, the jury was sworn (Jack Black, Daniel Byram, John Catlett, R.T. Chinn, David Huffman, James T. Humphries, John W. Musselman, Lee Newton, W.R. Raines, R.E. Shackelford, Strother Shackelford, and John Shelton). Shortly after noon, the jury took the case, required two hours to reach agreement on the sentence, but found him guilty (as he had pleaded) and fixed punishment at eight years in the penitentiary.

Judge Ashton instructed Sheriff Kennedy to deliver the prisoner to Richmond on Friday, May 17.

The Free Lance noted that the train robbery had occupied the news media for a full six months and it was time to drop it–and did so, except for a small squib in September which noted that Mrs. E.H. Searcey, wife of C.J. Searcey, the Aquia Train Robber, had been granted a divorce.