Anthony Burns

Anthony Burns was born into enslavement in Stafford around 1834. There were 13 children in his family. He and his father and brothers worked in the Robertson Stone Quarry, site of the present-day subdivision of Austin Ridge. (Stone from this quarry went toward the construction of the U.S. Capitol.) Anthony and his family belonged to the Suttle family. After Mr. Suttle’s death, Mrs. Suttle sold some of “Tony’s” siblings. After Mrs. Suttle’s death, her son, Charles Suttle owned Anthony. Charles rented Tony to a Stafford sawmill in Hartwood and other places in the county.

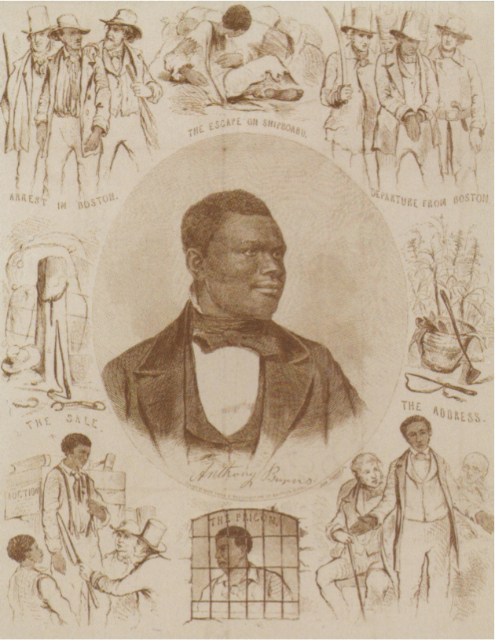

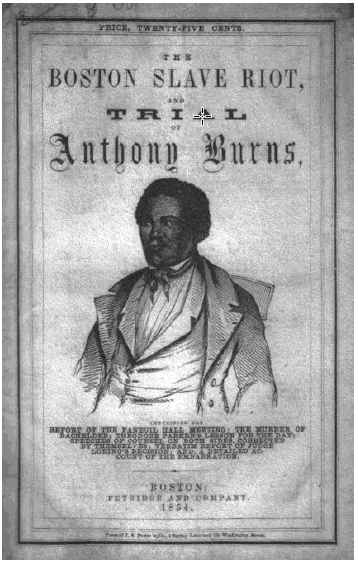

When Tony was about twenty years old he escaped to Richmond and stowed away on a ship which traveled to Massachusetts. He thought he was escaping to freedom since Massachusetts was a free state. However the Fugitive Slave Act mandated runaway slaves be recaptured and returned to their owner’s state. This law faced its first challenge when police captured Burns. The famous Richard Henry Dana Jr. was Anthony’s attorney. The nationally- known case put the spotlight upon this Staffordian and over 50,000 Bostonians favoring abolition rallied in the streets. The trial decided that Burns be returned to Virginia. Later on, Burns was sold to a North Carolina dealer of enslaved people; however, a group of Bostonians raised enough money to buy Burns’ freedom.

Anthony attended Oberlin College in Ohio and later became a minister in Canada. It is thought that Anthony Burns was the first black from Stafford to get a college education.

Fugitive Slave Act

The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act mandated that runaway slaves must be recaptured and returned to their master. A nationally-known test case of this law involved Anthony Burns. Born on a north Stafford estate managed by the Suttles (John H. Suttle, Sr. and John H. Suttle, Jr.), “Tony” Burns defied local laws by learning to read and write assisted by local white children. He worked throughout Stafford; north near the Robertson Quarry; in Hartwood at a sawmill; and in Falmouth as a Baptist “slave preacher” at the Union Church.

Doing an errand in Richmond for his enslaver, Charles Francis Suttle, Burns escaped from Virginia by stowing away on a north-bound ship. In February of 1853, he arrived in Boston, Massachusetts, a state where slavery had been abolished. He worked there for a year, but was arrested on May 24, 1854. The Fugitive Slave Act faced its first challenge when Boston police captured Burns. It touched off riots and protests by abolitionists and citizens of Boston. (Image: Library of Congress)

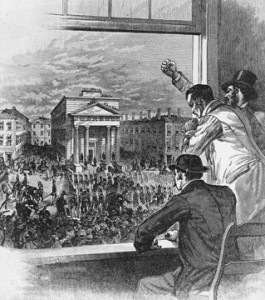

President Franklin Pierce sent a force of 2,000 militia and U.S. Marines to enforce law and order in Boston. A special federal judge ordered Burns’s return to enslavement. In addition to the people who streamed onto the downtown Boston streets, bells tolled in protest at churches. Anthony Burns, who had turned 20 years old while imprisoned, marched in chains through the city to an awaiting boat at Long Wharf. Boston’s merchants took their first stand with abolitionism. This caused economic pressures as they dealt with Southern enslaver cotton growers. Now engaged in the protest, they reportedly hanged pictures of President Pierce upside down. Outraged Bostonians draped their city in mourning and lined the route as Federal and state troops proceeded with Burns through the streets. The crowds were estimated between 20,000 and 50,000. Thereafter, the Fugitive Slave Act was not enforced in Boston. New England never returned another person to enslavement.

Anthony Burns’ Later Life

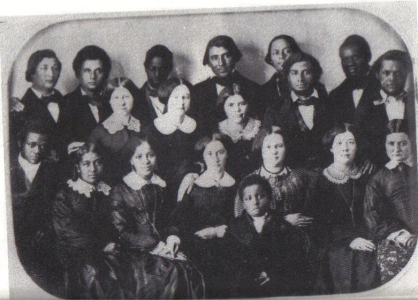

Returning to Virginia, Anthony Burns was sold by his enslaver, Charles F. Suttle, for $905 to a North Carolina enslaver, cotton planter, and horse dealer. Eventually, with financial aid from Boston and the help of friends, Burns’ freedom was purchased for $1,300. Once freed, Burns returned to live in Boston. With proceeds that came from his biography, as well as a scholarship, Burns received an education at Oberlin College in Ohio. (He is in the back row, on the right.) Later he went to Ontario, Canada, and was the minister of the Zion Baptist Church.

Anthony Burns had at least one more Stafford interaction. In July of 1855 he dutifully asked the Baptist congregation of Falmouth’s Union Church for a letter of good standing in order to transfer membership to a Northern church. He was rebuked and excommunicated on October 20, 1855. The delay perhaps suggested some intra-church debate. Burns responded with another letter which must rank among the most beautiful expressions of the early civil rights movement in America:

“Thus you have excommunicated me, on the charge of ‘disobeying the laws of God and man,’ in absconding from the service of my master and refusing to return voluntarily. I admit that I left my master (so called), and refused to return; but I deny that in this I disobeyed either the law of God, or any real law of men. Look at my case. I was stolen and made a slave as soon as I was born. No man had any right to steal me. That man stealer who stole me trampled on my dearest rights. He committed an outrage on the law of God; therefore this man stealing gave him no right in me, and laid me under no obligation to be his slave. God made me a man – not a slave; and gave me the same right to myself that he gave the man who stole me to himself… You charge me that, in escaping, I disobeyed God’s law. No, indeed! That law, which God wrote on the table of my heart, inspiring the love of freedom, and impelling me to seek it at every hazard. I obeyed, and by the good hand of my God upon me, I walked out of the house of bondage.”

(A Stafford school was named in honor of Anthony Burns, the first former enslaved person from Stafford to go to college.)