Slavery in Stafford County

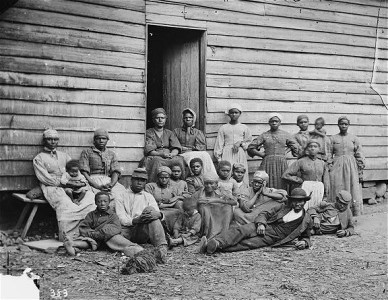

Slavery was part of the way of life for Stafford County. It is known that enslaved people worked on Brent’s Island (now known as Government Island) quarrying stone from 1694 to 1791. Sandstone, called Freestone or Aquia Stone, was used throughout Colonial America for architectural trim, making grave markers, and foundations. In December of 1791, Pierre L’Enfant purchased the island for the United States Government. From 1791-1825, slave labor quarried the stone which would be used in making the President’s House (White House) and the United States Capitol. Other quarries, throughout Stafford County (Robertson’s, Cooke and Brent’s, Edrington and Moncure, Rock Rimmon, etc.), used slave labor. Plantations with tobacco crops also depended upon slave labor.

Large homes, like Chatham (built in 1771) had around 100 enslaved persons to help run the household and fields. Chatham was a self-contained village with slaves taking care of every aspect of the plantation upon the 1,280 acres of land.

James Hunter of Falmouth used enslaved people for his plantation and large forge. Between his home and forge he owned 260 enslaved people, the largest single owner of enslaved people in Stafford’s history.

The 1860 census, prior to the Civil War, shows that the population of 8,633 was small and surprisingly quite evenly split between whites and blacks (4,018 whites and 3,715 blacks). The black population included 321 free blacks and about ten times as many enslaved, numbering 3,394. Slavery, however, was not as prevalent as the figures indicate, for out of 1,022 heads of white households in the county, 39% were enslavers. Most of those households enslaved fewer than five people. There were only two plantation owners with around 100 enslaved persons each. Those were J. Horace Lacy of the Lacy House (Chatham) and Gustavus B. Wallace of Little Whim.

Slavery would not die of its own accord. Virginia’s nearly half-million slaved persons were assessed at $33,000,000 in 1860 value.

Fearful of insurrection by those enslaved, Stafford militia grew. In 1851, Hartwood’s company held musters in April and October. Captain George Wellford Cropp’s Company, 45th Regiment of Virginia Militia, contained these families (some are misspelled): “Alexander, Armstrong, Anderson, Benson, Bridges, Bradshaw, Burton, Beach, Ballard, Brown, Bloxham, Bowling, Brooks, Bettis, Butler, Curtis, Conyers, Courtney, Dunnington, Dodd, Dye, Duerson, Ellignton, Ennis, French, Graves, Garner, Groves, Grinnam, Harding, Humphrey, Harris, Heflin, Herndon, Hickerson, Helm, Jackson, Jacobs, Jones, Johnson, Kellogg, Limbrick, Latham, Lunsford, Lane, Littrell, Leach, Monroe, Mills, Nash, Porch, Patton, Patterson, Powell, Rodgers, Rose, Roberson, Smith, Swetnam, Scooler, Stephens, Timberlake, Timmons, and Tompins.”

(Men from many Stafford families would later serve in the Civil War, mainly in the 47th, 30th and 40th Virginia Infantry Regiments, and the 9th Virginia Cavalry Regiment, as well as the Stafford Light Artillery and Fredericksburg Artillery.)