Native American Tribes

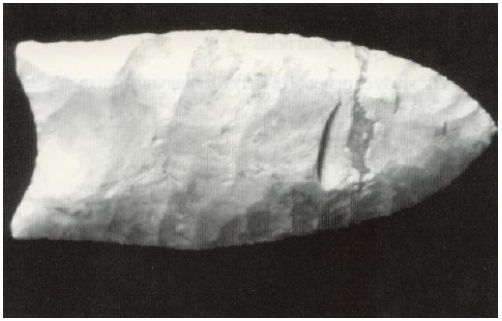

Recent discoveries reveal humans have been in Virginia for at least 16,000 years B.P. [Before Present] or 14,000 B.C. [Before Christ]. The earliest, known as Paleo-Indians, were “hunter-gatherers,” who arrived after the Ice Age. In small bands, they roamed grasslands hunting mastodon, bison, elk, deer, and smaller mammals, and gathered edible and medicinal plants, using a wide range of percussion-flaked stone tools and throwing weapons to hunt and prepare food. [Virginia Historical Society – VHS; Department of Historic Resources – VDHR]

About 10,000 B.P. (8,000 B.C.) (Archaic Period) there was a warming trend with decreased precipitation, exposing large sections of the continental shelf on which Tidewater Virginia sits. Forests adjusted, providing oak and pine trees. Hunter-gatherers, still classified as Paleo-Indians, developed greater reliance on plants and smaller animals, especially deer, turkey and turtle. From 8,500-5000 B.P. (6,500-3,000 B.C.), they mastered woodland habitats, refined stone weapons and tools, and continued to form larger “band-level societies” in temporary camps with family units.

With populations increasing and climatic changes spreading deciduous forests inland, they first moved into Virginia’s upland interiors above river fall-lines. As more permanent villages were established along streams and rivers, they evolved into “sedentary foragers.” Soon groups became tribal units and developed trade with other tribes (5,000 B.P. or 3,000 B.C.-900 A.D.). In the late Archaic Period, camps were pushed to the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains and the bands subsisted on varieties of nuts and small game while moving from one camp to another. [VHS; George Washington’s Fredericksburg Foundation – GWFF]

During the Woodland Period (3,200 B.P. or 1,200 B.C.-1600 A.D.), pottery (especially ceramic bowls), bows-and-arrows, food storage, more elaborate burials, corn and bean agriculture, and more formal societal structures (increased populations) appeared in the tribes. As hamlets and villages grew, the now American Indians or Native Americans increasingly turned to farming and more-developed tribal hierarchies and social infrastructures. During the Middle Woodland Period (c. 2,500 B.P. or 500 B.C.) Virginia’s Native Americans developed into tribes and took on many of the cultural traits we now associate with American Indians. [VHS; GWFF]

After 1607 A.D. (Historic Period) contacts with European colonists increasingly affected Indian tribes as new tools, technologies, religions, ideas, clothing and lifestyles were introduced. Some innovations yielded positive short-term results, but the net effect was a drastically diminished American Indian population and end of their way of life. Compared to the 50,000 Indians living in Virginia 90 years earlier, by 1700 only a few hundred were present. [VHS; GWFF]

Manahoacs and Powhatans (including the Potomacs or Potawomecks) were the Indians that had lived in the Stafford area.

Manahoacs (Mahocks or Mannahoacs), a tribal group which originated in the Ohio Valley and of the Siouan linguistic family, were likely related to the Monacan, Moneton, and Tutelo tribes. Virginia’s Manahoacs occupied the east-west territory between the falls of the rivers and the mountains, and from the Potomac River in the north to the North Anna River in the south. Subtribes were identified on the headwaters of the Rappahannock. The only Manahoac village known by name was Mahaskohod, located along the Rappahannock River. When Captain John Smith “discovered” them in 1608, they were at war with the Powhatan Empire and allied with the Monacans and probably the Susquehannas to the north. Manahoacs conceivably numbered 1,500 at that time. In the 1650s they camped on the falls of the James River and, in alliance with other tribes, defeated westward incursion by English settlers and their Indian allies (c.1654-1656). “Mahocks” were on the James River. In 1700-1723, they united with the Tutelo and Saponi. Per Jefferson (1801), the main division of the Manahoacs was in the western parts of modern Stafford and Spotsylvania Counties. [John W. Swanton – Swanton]

Manahoacs and Powhatans led annual raids against one another, but this hostility ceased under the greater threat of Englishmen. Before that, the Manahoacs (probably inhabiting present-day Hartwood and other areas above the Rappahannock’s fall line) were relatively powerful, accepting tribute from southern and western tribes, including the Shackakonies (Spotsylvania); Whonkenties and Tauxitanians (Fauquier); Tegninaties and Hassinungaes (Culpeper); and Ontponies and Stegarakies (Orange). Mahaskahod is believed by some archaeologists to have been located in Hartwood as a gathering place for ceremonial hunts. [Helen C. Rountree – Rountree; Lisa S. Anderson in Foundation Stones of Stafford County – Foundation Stones ]

The Powhatans were a tribe in the Algonquin linguistic group. The term originally referred to one tribal group but English settlers used it generally to describe the chief, Powhatan and his Powhatan Empire. This tribal alliance extended from the Potomac to the divide between the James River and Albemarle Sound, and east-west from Virginia’s Eastern Shore to the rivers’ fall lines. Powhatan’s Empire included modern Stafford and 20 other counties and described by Smith as having “32 Kingdomes ” with 161 villages:

The forme of their Common wealth is a monarchicall governement. One as Emperour ruleth over many kings or governours. Their chiefe ruler is called Powhatan, and taketh his name of the principal place of dwelling called Powhatan. But his proper name is Wahunsonacock. [Swanton; Foundation Stones ; Miriam Haynie – Haynie]

The Powhatan Empire’s tribal group in current Stafford and King George Counties was the Potomacs (Potawomecks, Patawomeks, etc.). Their main village, “Petomek,” was “about 55 miles in a straight line from the Chesapeake Bay, on a peninsula in what is now Stafford County, formed by the Potomac River and Potomac Creek.” The Powhatans were visited by explorers in the late 1400s, and were known to the Spanish. In 1570 Jesuit missionaries in Virginia were murdered by Powhatans near present-day Williamsburg. With Jamestown’s establishment in 1607, inevitable contact between the colonists and Indians occurred. Relations alternated between peaceful and warlike; but, during Chief Powhatan’s life, an accord was struck. The marriage of his daughter Pocahontas’ (Matoaka or Metoaka) to John Rolfe contributed to that peace. However, in 1622, Powhatan’s second successor, Opechancanough, led an Indian uprising against the colony, destroying all settlements except Jamestown and continued warfare until 1636. Another, equally devastating uprising took place in 1644, ending in Opechancanough’s capture and death. In 1675, Indians initiated raids, resulting in retaliation led by colonists under Nathaniel Bacon and “Bacon’s Rebellion” ensued. The Powhatans, perhaps numbering 9,000 in 1600, gradually were reduced by 1758 to two tribes, the Pamunkey and Mattaponi. The early 1800s saw Powhatans mixing with Virginia’s isolated black and white populations. This led to their essential disappearance. Lost in this mix were the Potomacs, becoming a “lost tribe.” [Swanton;Foundation Stones; Haynie]

When Captain John Smith explored the Stafford area, he encountered well-developed Indian villages. “Petomek,” on the Marlborough Point and Indian Point peninsula, had about 1,000 acres cleared for corn. Smith also encountered nearby Piscataways, Anacostins and Doegs living on both shores of the Potomac River its tributaries. Potomacs manned the northern frontier of the Empire against Manahoac incursions. Smith visited Quiyough or “the place of the gulls” [Aquia Creek], Potomac Creek and the Rappahannock River. From 1609-ca.1620, Virginia colonists established a trading post at Marlborough Point and the Potomacs, like their Powhatan brothers, soon developed a taste for English tools and weapons, trading food for them. The post was destroyed by Indians. [Jerrilynn Eby]

Another representative of English-Powhatan relations was Henry Spelman. The third son of Sir Henry Spelman of Congham, Norfolk, England, arrived in Jamestown in 1609 and was taken by Captain John Smith to visit Powhatan. Smith reportedly traded Spelman to Powhatan for a town-site near present-day Richmond. Powhatan later gave Spelman to the “King of Patowmeke,” putting him into the present-day Stafford and King George area. Pocahontas’ probable intervention saved the boy from her father’s wrath and may have also been the reason she visited the empire’s northern reaches. Spelman continued to live with the Indians, learning their languages. Exchanged, he returned to England. Mistreated, he came back to Virginia and acted as interpreter, trading with the tribes along the Potomac River between Potomac Creek to the falls of the river. He was killed by Anacostins. [Haynie]

Another Indian princess, Kittamaquad, played a more substantial role in Stafford’s history and English-Indian relations. Kittamaquad came over from Maryland with her English husband, Col. Giles Brent. They settled at a tip of land between Aquia Creek and the Potomac River naming their home Peace, as they wanted peace in this new land. They had it too, as Kittamaquad, although a Piscataway Indian, spoke the same Algonquin language as the Indians living in the western portion of Stafford. The land today is called Brent’s Point recalling the first settlers in Widewater.

Peaceful coexistence or assimilation might have solved colonist-Indian relations. In greater numbers than might be suspected, white and black colonists actually joined Indian societies, creating opportunities for an integrated and mutually beneficial society. Such chances passed quickly, however, as English colonial social order dispossessed the Indians of their lands. [James W. Loewen – Loewen]

Silver Medallion (obverse and reverse). Relations with the Indian nations became more formalized. In 1662, Virginia presented a silver medallion to “Ye King of Patomeck.” Such devices, used as “passports,” permitted safe passage for reliable allies to visit English Virginia settlements. Silver passports were issued to chieftains and copper to warriors. This particular specimen was excavated in Caroline County in 1832. Passports or badges for Indians, were described in 1663 colony law. (VHS; Warren M. Billings – Billings)