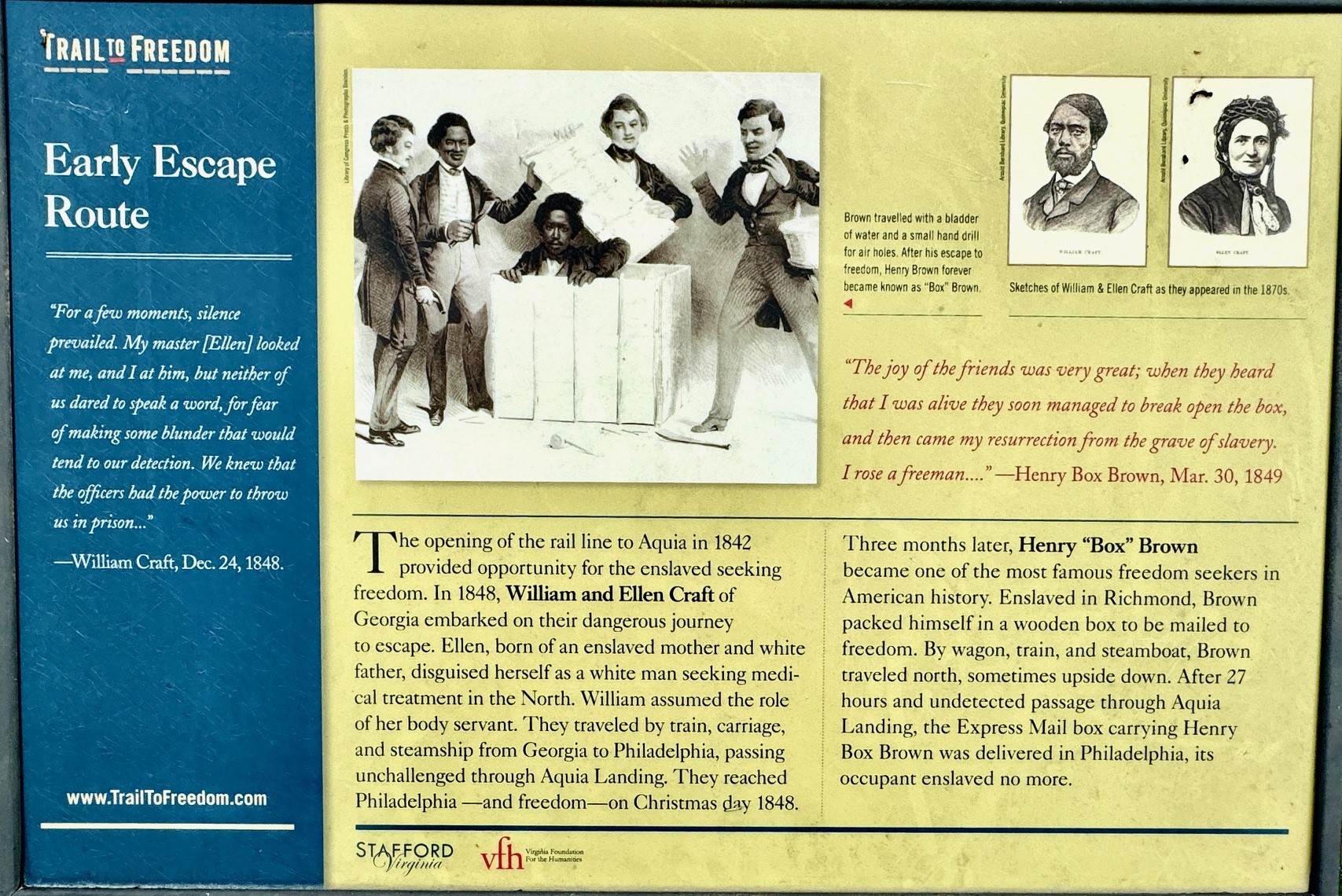

Henry Box Brown

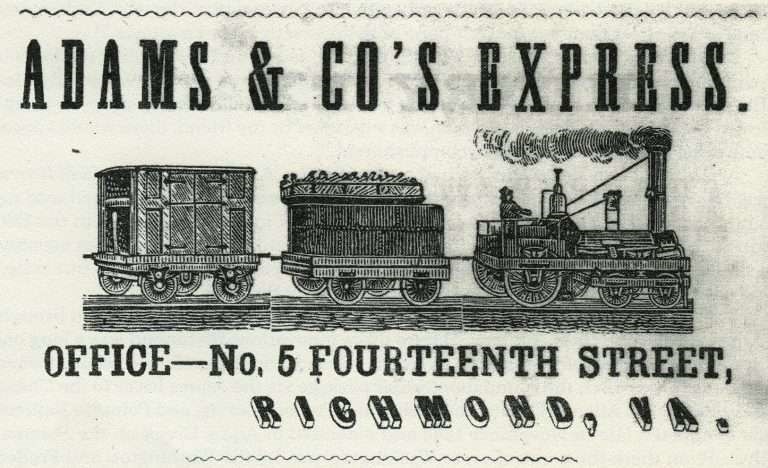

Henry “Box” Brown was enslaved in Louisa County, Virginia. Brown’s daring self-emancipation followed soon after his pregnant wife and three children were sold in August 1848 by the family’s enslaver to a Methodist minister in North Carolina. Distressed by this betrayal, Brown resolved to escape. He later recounted hearing in his mind the words “Go and get a box, and put yourself in it”. In March of the following year, with the help of others, he hired a carpenter to construct the box and have himself mailed by the Adams & Company Express, in Richmond, to Philadelphia. The company “promised never to look inside the boxes it carried”.

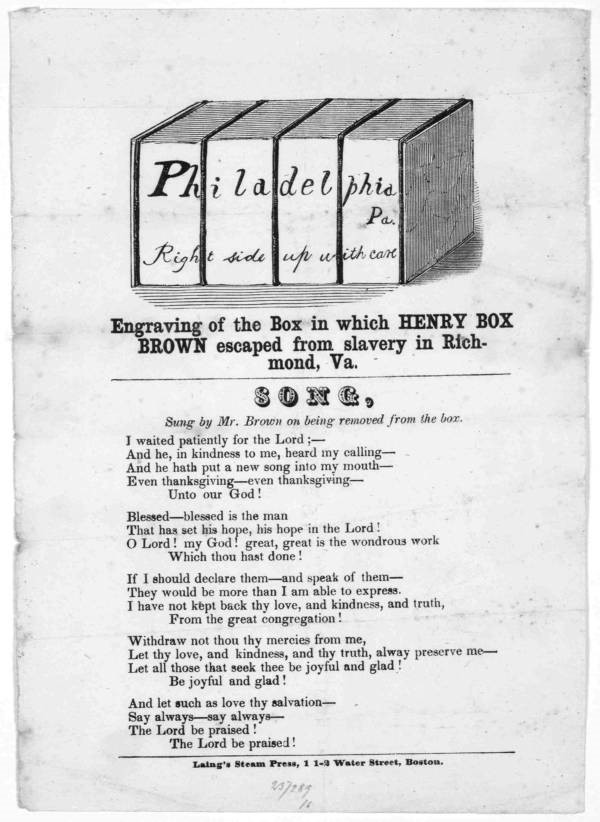

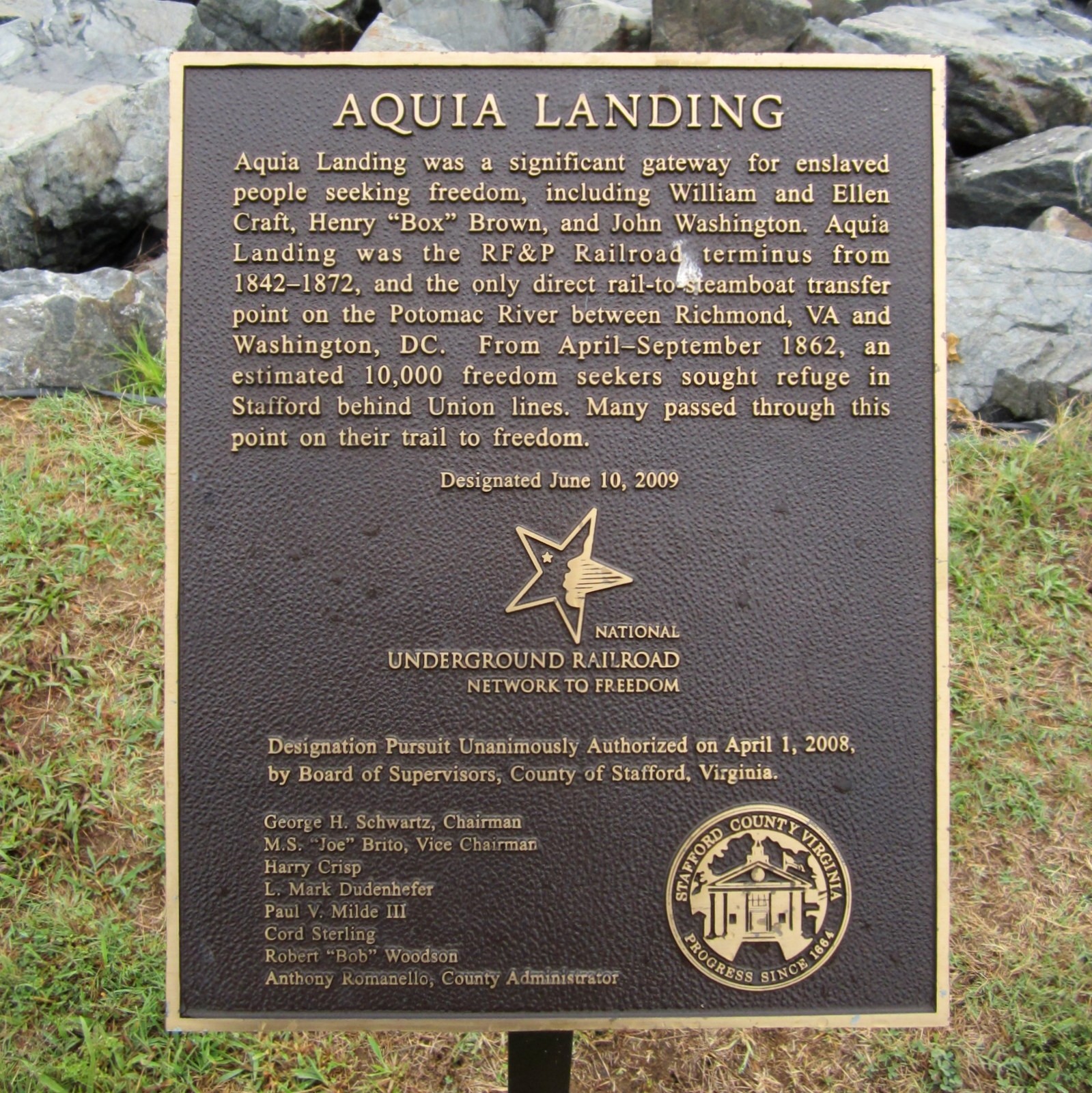

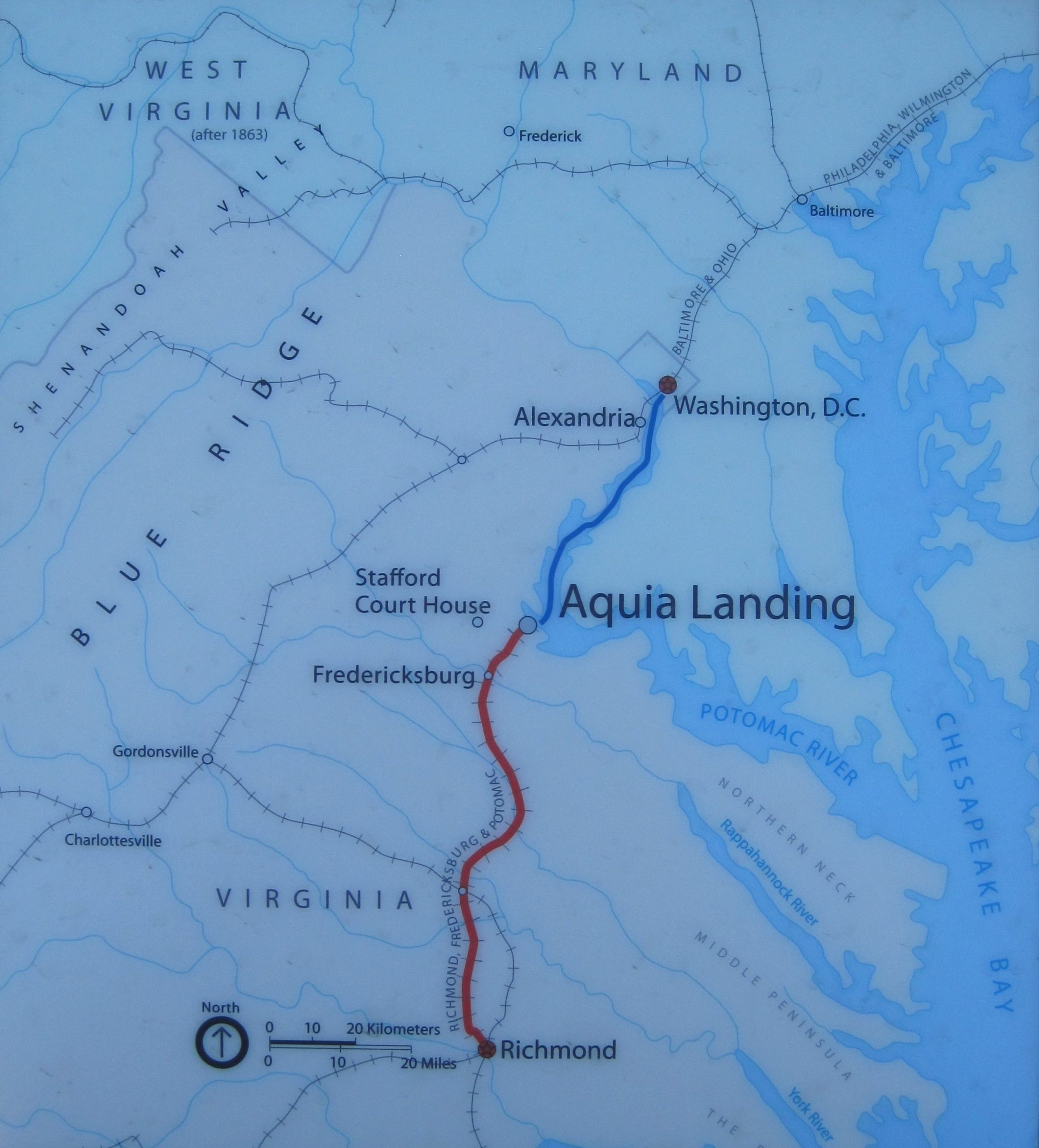

The start of Henry’s trip was March 23, 1849. He spent 27 hours in a 3x2x2½ foot Express Mail wooden box that was transported 350 miles via wagon, railroad, steamboat, wagon again, ferry, railroad again, and delivery wagon.

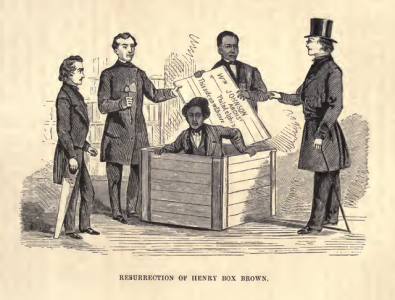

Brown spent much of the journey upside down, despite the markings “this side up’ and “handle with care”. He brought only a water bladder to “bathe [his] neck with, in case of too great heat”. After several hours of “terrible pain” in which death or discovery seemed an “inevitable fate”, the box, with Brown inside, arrived in Philadelphia, at the office of the secretary of the Anti-Slavery Committee. Brown would later write “The joy of the friends was very great; when they heard that I was alive they soon managed to break open the box, and then came my resurrection from the grave of slavery. I rose a freeman…”

Beginning in 1842, Aquia Landing was a slave transport route to the South, as well as the funnel to the North for many escaped or emancipated people before and during the Civil War, but Brown is among the few whose names and stories we know in detail.

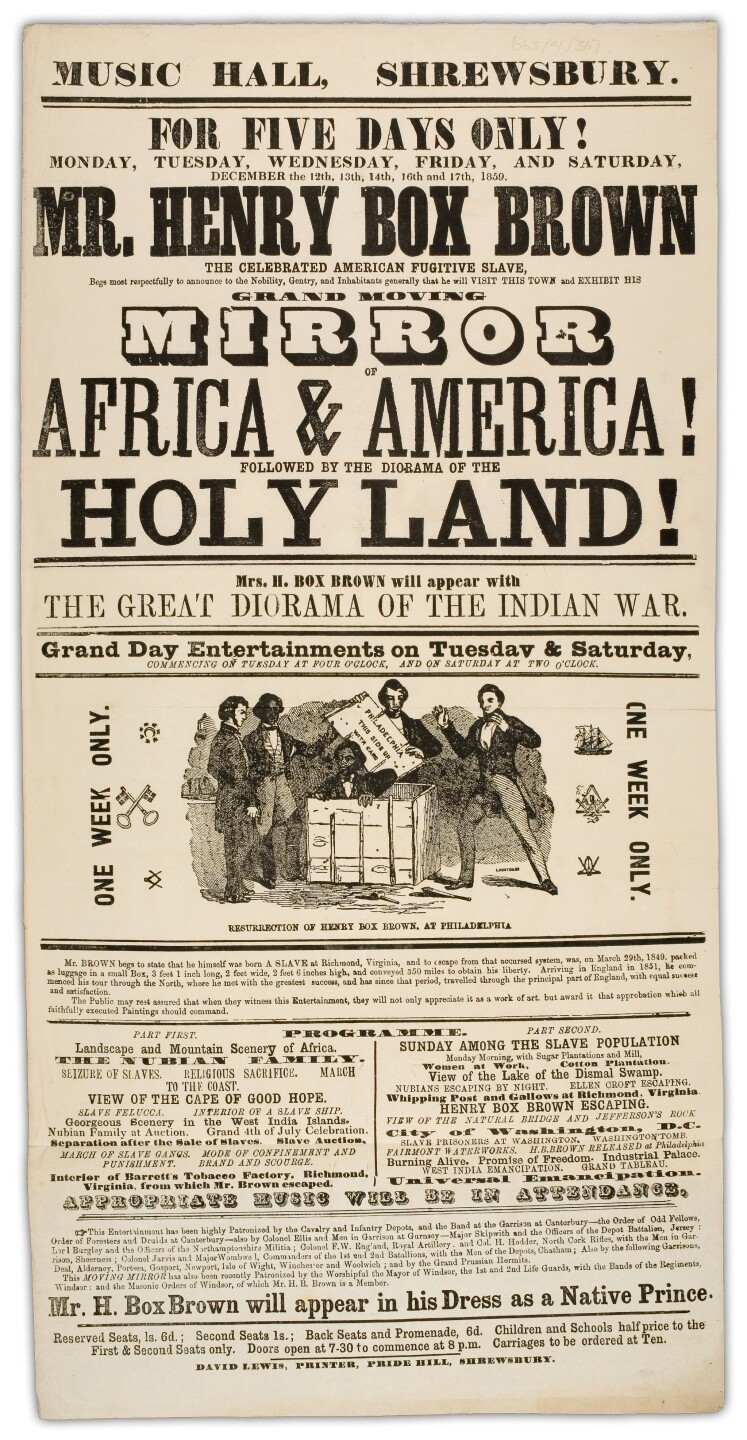

News of Brown’s success spread widely, but his fear of the Fugitive Slave Act, passed in 1850, provoked his moving to England in 1851. He remained there for 25 years, touring with his box, as a speaker in an anti-slavery panorama and magician, before returning to the United States in 1875.

He wrote two accounts of his life story, one in 1849, and the second in 1851, in England, where he later remarried. He was never reunited with his first family, though the opportunity presented itself. Members of the Black community, including Frederick Douglass, expressed displeasure about Brown’s revealing the method of escape and also about his abandoning his first wife and children. Brown and his second wife moved to Toronto in 1886, where he died in 1897, aged 81 or 82.