Espionage

Desperate measures taken in the “‘Come Retribution’ Campaign” were weighed down by the South’s inherent strategic weaknesses and human errors, not to overlook concrete Union actions. These caused the Southern plans to mostly fail. Fortunately for America’s future, the Confederate efforts were “too little, too late.” The grand strategic plans were simply beyond the capabilities of the nascent Southern nation and the nineteenth century state-of-the-art warfare.

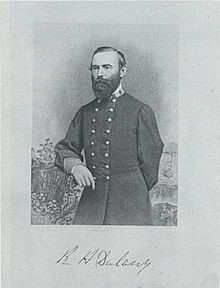

Espionage continued with a new urgency and targets of opportunity were increasingly sought. Stafford “Secret Line” activity, evidenced by this letter, was still operative in July 1864; Julia B. Whiting (1840-1924) wrote to her uncle, Col. Richard H. Dulany, 7th Virginia Cavalry, from Stafford’s “Richland” in Widewater:

Richland, July 27th ‘64

Dear Uncle, I can hardly find words in which to express my pleasure at receiving the package of letter for me today by some person unknown. Neville [her brother, age 10] and I were busily engaged in our morning reading of Rollin, deep in the campaigns of the great Cyrus [biblical king of Persia], but since the arrival of your letter, we are neither of us in the mood for enjoying the achievements of any soldiers but our own gallant Southerners…

We see very few Richmond papers; our accounts of the various engagements and raids which have taken place this spring and summer are therefore always given by the Yankee papers, so that independently of the pleasure of hearing from you, it has been a great gratification to receive the description of all our successes from an eye witness…

We had a visitor a week since whom I was quite pleased to meet, having heard so much of him from Col. Henry Arthur [Hall] and Coz Eliza — Mr. Dunlop, formerly on Gen. Armistead’s staff [then a charge d’affaires for the Confederacy in London]. You may remember him, as he was for some time at Coz H.A.’s while wounded. He brought his wife to the neighborhood, and I invited them to stay until they could cross the river, as they were on their way North. Mr. D., having left the army on account of his health, was returning to England. His wife was a sister of Col. Maury of the Cav. and cousin of the Maury’s in Richmond. As they were just from Richmond and acquainted with all our friends and relations there and in Baltimore, their visit was an agreeable interlude in our quiet life…

When do you expect Grant to be driven from Virginia? He certainly has more tenacity of purpose than any Northern general has yet exhibited. I hope nevertheless he may meet with the fate of his predecessors.

I’m afraid my feelings would accord better with Fanny’s than yours with regard to the Yankees. I certainly never could say “Spare him, he our love hath shared.” If I would have our own men spare them, it is rather that I wish our soldiers to treat them according to their own dignity than to their foe’s deserts.

…The ruffians who have ravaged our land can only be punished fitly by those who could equal them in baseness. I would not have our Christian soldiers sully their laurels by a single action resembling those of our enemy.

I hate to think of our men destroying private property across the line, though I know that necessity compells us to retaliate. Of course everything depends upon the spirit in which it is done, yet I cannot help fearing that in thus retaliating our men may lessen the high honorable feelings which they have displayed during the war. I love the honor and glory of our own army more than I hate the Yankees, much as I detest them.

Quoted from Margaret Ann Vogtsberger, Editor, The Dulanys of Welbourne: A Family in Mosby’s Confederacy, (1995) pp 185-189. With regard to “Mr. Dunlop,” this work states his first name was William. Crute’s Confederate Staff Officers lists Lt. John Dunlop as having served on Brig.Gen. L. A. Armistead’s staff as volunteer aide-de-camp June and July 1862, aide-de-camp October 29, 1862, and as having resigned on February 7, 1863. Dunlop was using the “Secret Line” to make his way north to travel to his London post.