The Epidemic of 1814

By Jerrilynn Eby MacGregor

As a historian, I sometimes become aware of trends or patterns as I piece together Stafford’s past. My occasional work with the dedicated volunteers of Stafford County’s Cemetery Committee helped me to recognize one such pattern. As we traveled around to cemeteries recording the inscriptions and other data from gravestones, I noticed that quite a number of people died during the winter of 1814-1815. Some had obituaries, some didn’t. Some have known burial locations, some don’t. The common pattern was the time period in which they died. There seemed to be too many deaths within a restricted time period to be mere coincidence.

The Farmer’s Repository of January 26, 1815, an agricultural magazine, included an article from the January 3, 1815 Richmond Enquirer newspaper. This was titled “Extract of a letter from a gentleman in the county of Stafford, to his correspondent in this city dated Falmouth Jan. 3.” This read:

I have seen James Waller to-day, just from Aquia; he had been in pursuit of a Doctor to attend his brother William, who was taken yesterday with a complaint which has destroyed so many of our inhabitants. Mr. Garnett died a few days ago at Aquia. The distemper is distressing beyond anything that you can imagine. It takes off whole families. I am fearful to send any of my family to Aquia. John Cook lays at the point of death; his father has been down to see him and was fearful to go into the house. If the disease does not abate, I am apprehensive it will destroy the greater part of our inhabitants. In King George, there was a family of ten—the whole dead except a little boy, who went to a neighbor’s house, after starving a day or two, and asked for some bread. The neighbor asked him if he had not a plenty of bread at home; he said that his father, and the rest of the family were asleep, and that he could not wake them. He was asked how long they had been asleep? He said a day or two. The neighbours went over and found nine of them dead! They were so much alarmed they concluded it would be the best way to set fire to the house and burn them up; which was done. Poor Andrew Leach, his wife, son and daughter, are dead. Old Mr. James Steward has lost his son Stephen and his daughter Sally; his daughter Nancy is now very ill at Mr. Norman’s place. Old Mr. Carpenter and his son is also dead. Mr. Ball, just below the Court-house, has made 13 coffins in the course of 8 or 10 days.

To this the Farmer’s Repository added:

The alarming disease, noticed in the above letter, has existed for several weeks in some of the portions of the seaboard. In the Northern Neck, especially, it has made the greater ravages. It frequently kills from 6 to 13 hours – it principally preys upon the heartiest and most robust patients. The physicians are at some loss to describe or to treat it. Some describe it as a Typhus fever – others as a violent inflammatory sore-throat, the most of them as a putrid sore-throat. It affects the throat most violently and obstructs the circulation of the air through the wind-pipe. In a few instances, as in the one above stated, the houses in which the dead have laid, have been burnt down to prevent the diffusion of the contagion.

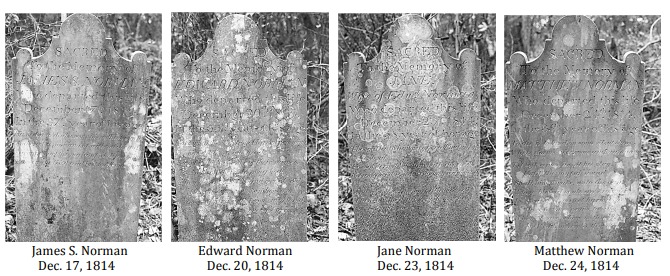

The infection swept through Stafford County, affecting rich and poor, black and white. At Edge Hill in Widewater, Edward Norman (1752-1814) and his wife, Jane (Stewart) Norman (c.1756-1814), along with their two sons, James S. (c.1777-1814) and Matthew Norman (c.1779-1814), all died within a few days of each other and close to Christmas. At Concord on Aquia Creek, Ursula (Withers) Waller (1750-1815) and her son, William Waller, Jr. (c.1773-1815), succumbed along with enslaved, Mary Lam (c.1767-1815). Further upstream on Aquia Creek, Robert King (c.1765-1814) and Catharine Green (c.1785-1815) may also have been victims. Their graves are located in what’s now Widewater Park. Daniel Carroll Brent (1759-1815) of Richland and his brother, Senator Richard Brent (1757-1814), both died suddenly during this period. These are but a very few individuals who passed away in this time frame and, quite possibly, from this virulent infection.

Because so few graves in Stafford are marked with inscribed tombstones, it’s not possible to know the full impact of the disease upon the county residents.