Chatham / Lacy House

This magnificent Georgian mansion, its various outbuildings and dependencies, and the historic ground which surrounds it represent a small preserve in which the entire scope of Virginia heritage can be understood and appreciated. Today Chatham is part of Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park. The buildings and grounds are open daily 9:00-4:30. Five of the ten rooms contain exhibits and the rest of the building as well as the outbuildings are park offices.

Below is the text from the park’s Chatham brochure.

Chatham History

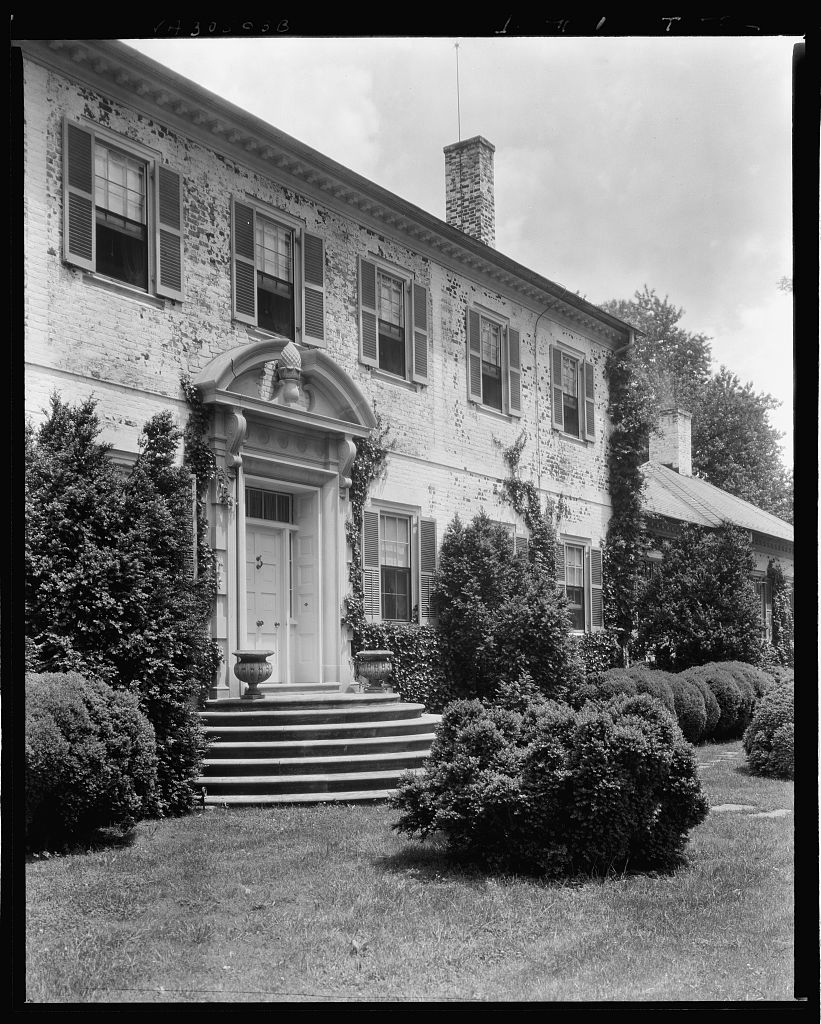

Few houses in America have witnessed as many important events and hosted as many famous people as Chatham. Built between the years 1768 and 1771 by William Fitzhugh, this grand Georgian-style house overlooking the Rappahannock River was for many years the center of a large, thriving plantation. Flanking the main house were dozens of supporting structures: a dairy, ice house, barns, stables. Down on the river was a fish hatchery, while elsewhere on the 1,280 acre estate were an orchard, mill, and a race track, where Fitzhugh’s horses vied with those of other planters for prize money. The house was named after William Pitt, the Earl of Chatham.

Fitzhugh enslaved upwards of one hundred people. Most worked as field hands or house servants, but he also employed skilled tradesmen such as millers, carpenters, and blacksmiths. In 1805, a number of the enslaved people rebelled, overpowering and whipping his overseer and four others. An armed posse put down the rebellion and punished those involved. One black man was executed, two died while trying to escape, and two others were deported, perhaps to a colony in the Caribbean.

At the time of the insurrection, Fitzhugh was living in Alexandria. he had moved there in the 1790’s, in part to escape the hundreds of guests who came to Chatham each year. The expense of providing food and entertainment gnawed at the aging landowner’s pocketbook and undoubtedly contributed to his decision to move. Although the very idea caused him to “shudder,” Fitzhugh left Chatham in 1796 and put the house for sale.

Major Churchill Jones, a former officer in the Continental Army, purchased the plantation in 1806 for 20,000 dollars. His family would own the property for the next 66 years.

Famous Visitors to Chatham

Robert E. Lee was a guest at the home during the Jones’s ownership, though there is probably no truth to the story that he courted his wife here. (The future Mrs. Lee never lived at Chatham and there is no evidence that she visited her grandparents house). Lee was not the first famous Virginian to visit Chatham. George Washington, had stopped at the house on two occasions in the 1780’s (he grew up at what is now called Ferry Farm a few hundred yards south of Chatham). Both Washington and Fitzhugh served together in the House of of Burgesses prior to the American Revolution, and they shared a love of farming and horses. Fitzhugh’s daughter, Molly, would later marry the first president’s step-grandson (and adopted heir), George Washington Parke Custis, whose daughter in turn would wed Robert E. Lee. The Fitzhugh’s were also good friends of Thomas Jefferson. Mrs. Fitzhugh was a second cousin of Jefferson. For many years we assumed that Jefferson visited Chatham, but could not prove it. Recent research found documentation that Jefferson visited the Fitzhughs at Chatham on October 27, 1793. President-elect William Henry Harrison was on the grounds of Chatham, but did not come inside. The Civil War would bring more famous Americans to Chatham.

The Civil War

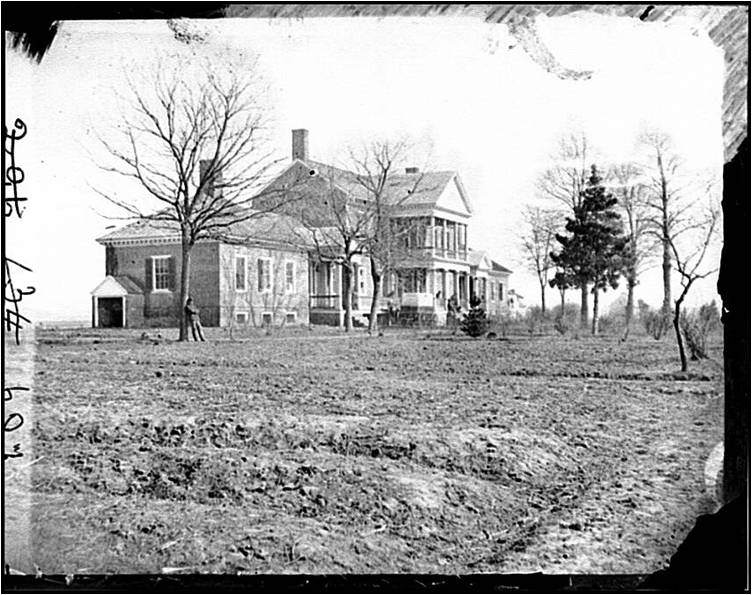

The Civil War, which gave Lee fame, brought only change and destruction to Chatham. At the time the house was owned by James Horace Lacy, a former schoolteacher who had married Churchill Jones’s niece. As a plantation owner and enslaver, Lacy sympathized with the South, and at the age of 37 he left Chatham to serve the Confederacy as a staff officer. His wife and children remained at the house until the spring of 1862, when the arrival of Union troops forced them to abandon the building and move across the river. For much of the next thirteen months, Chatham would be occupied by the Union army.

Northern officers initially utilized the building as a headquarters. In April 1862, General Irvin McDowell brought 30,000 men to Fredericksburg. From his Chatham headquarters, the general supervised the repair of the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad and the construction of several bridges across the Rappahannock River. Once that work was complete, McDowell planned to march south and join forces with the Army of the Potomac outside of Richmond. President Abraham Lincoln journeyed to Fredericksburg to confer with McDowell about the movement, meeting with the general and his staff at Chatham. His visit gives Chatham the distinction of being just one of three houses visited by both Lincoln and Washington (the other two are Mount Vernon and Berkeley Plantation).

Seven months after Lincoln’s visit, fighting erupted at Fredericksburg itself. In November 1862, General Ambrose E. Burnside brought the 120,000-man Army of the Potomac to Fredericksburg. using pontoon bridges, Burnside crossed the Rappahannock River below Chatham, seized Fredericksburg, and launched a series of bloody assaults against Lee’s Confederates, who held the high ground behind the town. One of Burnside’s top generals,

Edwin Sumner, observed the battle from Chatham, while Union artillery batteries shelled the Confederates from adjacent bluffs.

Fredericksburg was a disastrous Union defeat. Burnside suffered 12,600 casualties in the battle, many of whom were brought back to Chatham for care. For several days army surgeons operated tirelessly on hundreds of soldiers inside the house. Assisting them were volunteers, including poet Walt Whitman and Clara Barton who later founded the American chapter of the International Red Cross.

Whitman came to Chatham searching for a brother who was wounded in the fighting. He was shocked by the carnage. Outside the house, at the foot of a tree, he noticed “a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, etc.-about a load for a one-horse cart. Several dead bodies lie near,” he added, “each covered with its brown woolen blanket.” In all, more than 130 Union soldiers died at Chatham and were buried on the grounds. After the war, their bodies were removed to the Fredericksburg National Cemetery. Three additional bodies were discovered years later. They remain at Chatham, their graves marked by granite stones lying flush to the ground. Recent research also associates Dr. Mary Walker with being at Chatham. Walker was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, the only woman from the Civil War to be so recognized.

In the winter following the battle, the Union army camped in Stafford County, behind Chatham. The Confederate army occupied Spotsylvania County, across the river. Opposing pickets patrolled the riverfront, keeping a wary eye on their foe and occasionally trading newspapers and other articles with them by means of miniature sailboats. When not on duty, Union pickets slept at Chatham. As the winter progressed and firewood became scarce, some soldiers tore paneling from the walls.

Military activity resumed in the spring. In April, the new Union commander, General Joseph Hooker, led most of the army upriver, crossing behind Lee’s troops. Other portions remained in Stafford County including John Gibbons’ division at Chatham. The Confederates marched out to meet Hooker’s main force and for a week fighting raged around a country cross-roads known as Chancellorsville. At the same time, Union troops crossed the Rappahannock at Fredericksburg and drove a Confederate force off of Marye’s Heights, behind the town. Many of 1,000 casualties suffered by the Union army in that engagement were sent back to Chatham.

The Postwar Years

By the time the Civil War ended in 1865, Chatham was desolate. Blood stains spotted the floors; graffiti marred its bare plaster walls. Outside the destruction was just as severe. The surrounding forests had been cut down for fuel; and the lawn had become a graveyard. Although the Lacy’s returned to their home, they were unable to maintain it properly. They moved to another house they owned called Ellwood and sold Chatham in 1872.

The property languished under a succession of owners until the 1920’s when Daniel and Helen Devore undertook its restoration (and made significant changes). As a result of their efforts, Chatham has regained its place among Virginia’s finest homes. Today the house and 85 surrounding acres are open to the public thanks to the generosity of Chatham’s last owner, industrialist John Lee Pratt. Mr. Pratt purchased Chatham from the Devores in 1931 and in 1975 willed it to the National Park Service. Five of the ten rooms in the 12,000 square-foot mansion are open to the public. From the entry hall, visitors are encouraged to begin their house tour in the dining room. Here, exhibits depict Chatham’s fifteen owners. Across the hall, displays in the parlor describe the property’s role in the Civil War.

Chatham Gardens

Visitors are also free to wander on the grounds, in the gardens, and among the outbuildings at their leisure. The interiors of the outbuildings are not open to the public, so please view these structures from the outside only.

The National Park Service began the restoration of the 1920’s colonial revival east garden in 1984. The walls, statues, and Ionic columns, represent this period. At the front of the building, the original entrance road winds its way down the bluff to the river. The front terraces offer a panoramic view of Fredericksburg landmarks on the city skyline and point to the places where Northern engineers erected their pontoon bridges during the Battle of Fredericksburg.

On the river side of the house, the outline from the two-story Greek revival porch, which graced the front entrance for nearly 100 years, is still visible. The present limestone entrances were added in the 1920’s.

If you walk the grounds at Chatham you will see that several ornamental cast concrete pineapples adorn the landscape. This colonial decoration served as a symbol of hospitality, a tradition which the National Park Service strives to continue.