Gold Mining

History:

Gold was discovered in Virginia in 1782, a nugget being found on the Stafford side of the river a short distance downstream from the falls. Serious mining didn’t commence until around 1830 and continued until the outbreak of the Civil War. While mining at most sites ceased during the war, it may have continued at Eagle/Rappahannock Gold Mine.

Gold Mines in Stafford:

Most of the Stafford mines were located between Warrenton Road (Rt. 17) and the Rappahannock River and from about Richland Church to the Fauquier County line. The names of the most prominent Stafford gold mines: Brower, Eagle/Rappahannock, Franklin, Horsepen/Rattlesnake, Lee, Monroe, New Hope, Pris-King, Smith, Stafford, and Three Sisters. There were numerous other small mines and prospects, some of which were unnamed.

Gold Mining Technology:

At nearly all Stafford mines gold was dug from shallow pits or washed from stream gravels. Eagle, also known as Rappahannock Gold Mine, was the county’s most profitable mine and was one of only three mines that took gold from deep shafts.

Gold found in stream deposits is called placer gold and this is the easiest to work as little digging is required. The earliest mining operations involved placer deposits and were worked either by panning or by washing stream gravel and sand in large rockers that separated the waste material from the small gold flakes.

Lode deposits consist of veins of gold surrounded by layers of quartz. Locally, a few gold bearing veins are up to 20 or more feet wide, but most have a width of less than 12 feet. Pink-hued quartz often contains more gold than white or clear quartz. Ore dug from lode deposits must be crushed quite fine before the gold can be removed. This crushing might be accomplished with a sledge hammer or using various types of crushing machines. Some mine owners built their own crushers, others purchased steam or horse-powered crushers from mining supply companies.

Once the ore was crushed to a coarse powder it was washed to remove as much of the waste material as possible. What remained was then mixed with mercury to form an amalgam. The gold mixed readily with the mercury and the mixture was then squeezed through a cloth to remove extra mercury and waste. The next step was to heat the amalgam until the mercury vaporized; what remained in the dish was nearly pure gold in the form of a powder. The powdered gold was then mixed with saltpeter, melted, and cast in iron molds. Because mercury was expensive, many mines used clay-lined retorts fitted with pipes to collect the mercury vapor. As it cooled, the vapor returned to its liquid state and could be re-used. Over the years, various methods of dealing with the amalgam were developed and utilized. There was little concern about the toxicity of the mercury and miners routinely handled it without gloves or masks.

Problems that Discouraged Mining in the Stafford Region:

Mines that were limited to placer deposits usually yielded less than lode mines. In Stafford only Eagle/Rappahannock, Smith, and Monroe mines had these types of deposits. 19th century shaft mines were plagued by underground springs and the technology of the period simply couldn’t deal adequately with this problem. When gold was discovered in California in 1849, many of Stafford’s mines closed and the miners working them went west to try and make their fortunes in California.

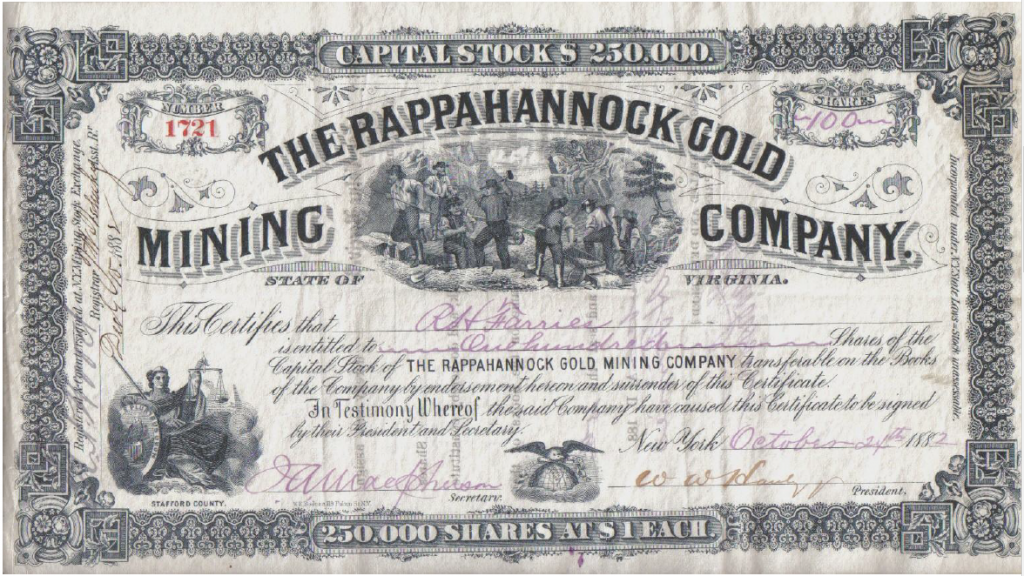

During the 1830s, wild land speculation drove property values to absurd heights, making the purchase of gold-bearing land extremely costly. Mining machine companies charged enormous prices for equipment and small villages had to be built on site to house workers and provide necessary buildings for equipment and storage. Miners and other workers had to be paid. Mine owners frequently assumed great debt even before they knew whether or not their mines would be profitable. A few mines such as Eagle/Rappahannock and Monroe sold stock to investors and used that money to cover their expenses. It has been correctly stated that in Stafford County more money was made selling land and stock than was ever made from the mines themselves.

Sources:

- Ahnert, Gerald T. “The Gold Mines of Virginia.” Lost Treasure, August 1981, pp. 62-66.

- Barron, Bob A. Gold Mines of Fauquier County, Virginia. Warrenton, VA: Warrenton Printing and Publishing Co., 1977.

- Clemson, Thomas G. “Notice of a Geological Examination of the Country Between Fredericksburg and Winchester in Virginia, Including the Gold Region.”

- Transactions of the Geological Society of Pennsylvania, (1835), pp. 298-313.

- Clemson, Thomas G. “Report of the Committee Appointed by the Geological Society of Pennsylvania to Investigate the Rappahannock Gold Mines, in Virginia.” Journal of the Geological Society of Pennsylvania, (Aug. 11, 1834), pp. 147-167.

- Heylmun, Edgar B. “Gold in Maryland and Virginia.” California Mining Journal, vol. 55, # 8, (April 1986), pp. 34-37.

- Park, C. F. “Preliminary Report on Gold Deposits of the Virginia Piedmont.” Virginia Geological Survey Bulletin, #44, Charlottesville, VA, 1936.

- Sweet, Palmer C. “Gold in Virginia.” Commonwealth of Virginia, Department of Conservation and Economic Development, Division of Mineral Resources, Charlottesville, VA, 1980.

- Sweet, Palmer C. and Trimble, David. “Gold Occurrences in Virginia, an Update.”

- Virginia Minerals, vol. 28, #4 (November 1982), pp. 33-41.

- Sweet, Palmer C. “Precious-Metal Mines, Prospects, and Occurrences in Virginia, an Update.” Virginia Minerals, vol. 37, # 1, (February 1991).

- Whitney, Josiah D. Metallic Wealth of the United States. NY: Arno Press, Inc., 1970.