Pocahontas

Through centuries of Western Civilization members of Royalty have not always brought honor to their noble offices nor filled their subjects with pride in their accomplishments. Virginia’s Princess, daughter of its most powerful native chieftain did both.

Born to one of the almost one hundred wives of Powhatan, the little Metoaka was an instant favorite of her father and was nicknamed Pocahontas or “the little mischievous one.” At about the age of twelve she was caught climbing the steeple of the new church being constructed in Jamestown, proof of the fact that she probably earned her nickname long before the arrival of the English settlers. Pocahontas remembered very early in her childhood being trained almost as a young brave, learning to swim, run, and use a bow and arrow while she was still quite small. Accompanied by her elder brothers, she was allowed to dress in deerskin leggings and join her father on hunts for small game. To prove her special status she was allowed to sit close to her father in the all-male tribal councils, a privilege afforded no other Indian woman.

As a result of this special upbringing, Pocahontas did not become the expected “spoiled daughter of royalty” but a capable, self-reliant young woman who was about twelve years of age when she first encountered John Smith and his English explorers. Smith, explaining to Powhatan that he was searching for a water outlet to the other “great sea” was well received by the chieftain and he was allowed to move freely along the Virginia waterways leading out of the Chesapeake Bay, the James, the Rappahannock and the Potomac. During these expeditions, according to Smith’s account, his most famous encounter with Pocahontas took place, one in which she threw herself across his prone body to plead for a stay of execution, which had been ordered by her father.

Historians have long doubted this account by Smith for several reasons. One reason was that Powhatan had acted more as a gracious host than an executioner up to this point in his relations with these English “invaders.” Second, Smith’s “True Relations . . .” and his “General Historie . . . “had gone through several publications in England and did not contain this adventure. It was added to the third printing just at the time sales were beginning to lag in England. Third, and probably the reason the story is most regarded as unlikely is the fact that in 1630 Smith published his “True Travels . . . in Europe, Africa, Asia, and America,” in this lengthy journal he had no less than three miraculous escapes from death due to the intervention of a beautiful, high-born woman, ranging from the daughter of a Turkish war lord to a Polish countess.

However, the Princess Pocahontas does seem to have been excited and charmed by these strange visitors from another civilization. She reports slipping away from her father’s compound, without his permission, and making her way to Jamestown just for a glimpse of these new arrivals in her homeland. She seems to have played a real role in relation to John Smith during his first two hard winters on the Virginia shores. She personally headed bi-weekly visits to the settlement bringing corn, fish, and game from her father’s storehouses. This was to a large extent responsible for the success of England’s Virginia Colony during the first few years.

This interdependent relationship may explain why both Powhatan and his daughter were so dismayed when John Smith left the colony suddenly in October of 1609 without advising either of his plans for departure. They may have known of his grave physical injury as a result of exploding gun powder, but they were probably unaware of the political machinations in the small colony that drove him back to the mother country. During the next year an uneasy truce between Indians and settlers deteriorated into open warfare. Colonists dared not leave the Jamestown Fort and no provisions were being sent by Powhatan to relieve what was to become known as “the starving time.”

In May of 1610, when ships arrived bringing 150 new settlers to the Jamestown Colony, they were appalled to find only about 60 ill and undernourished remnants of the 400 colonists they had been told would be awaiting their arrival. The new colonists made the decision to return to England taking the remaining 60 with them. On June 7, 1610 they set sail only to be met at the mouth of the James River by an English fleet bringing the new governor, Lord de la Warre. On that morning, except for a few hours, England’s second attempt at a colony in North America would have ended in failure.

The deserters returned to Jamestown and new provisions and a new administrator renewed the hopes for success. Governor de la Warre’s first concern was to improve relations with Powhatan and his Indian Confederation. Laden with gifts for “King Powhatan,” the governor made his way in a colorful expedition to the Chieftain’s headquarters. Here he pitched bright silk tents which impressed Powhatan as tents belonging to a great leader and for the first time since the departure of John Smith feasts were ordered in honor of the English guests.

We hear of Pocahontas again as Governor de la Warre and his wife return the hospitality they had received by preparing a great feast in Jamestown. The powerful head of the Indian Nation arrived with a group of about 60 to 70 Indians made up of lesser chieftains and his relatives, among them his two elder sons and his daughter, Pocahontas. The governor’s wife, Lady de la Warre, was much impressed by the young Indian girl, her pose, her natural curiosity about the many things that were so strange to her and her charming acceptance of customs and rituals what were totally unfamiliar Lady de la Warre wrote a number of letters to friends back home in England and they paint a vivid picture of the young Virginia native. “She was tall with chiseled features and a natural grace and dignity that much endeared her to me,” Lady de la Warre wrote. “She was endowed with great feminine delicacy and was most interested in everything English.” The governor’s wife tells of Pocahontas touching with awe damask draperies and bedspreads in the governor’s quarters. She drank English tea with great pleasure, but found the wine not at all to her taste and after one sip left the rest in her goblet. Lady de la Warre described the Princess’ first encounter with a knife and fork and with a linen napkin. Most of Powhatan’s party were confused by the accouterments of the banquet table but Pocahontas watched and imitated her hostess, laughing good-naturedly when she made a mistake.

There were further invitations for the young princess to visit the first lady and they formed a firm friendship. It was from Lady de la Warre she learned her first English words, learned the meaning of books and learned to sleep in a feather bed. It was from her she received her first outfit like the ones worn by English ladies. She wore the dress on her return to her father’s encampment but refused to wear the shoes. However, she did insist on taking them with her carefully tucked under her arm as her Indian moccasins peeked out from beneath her full silk skirts. Her older brother, Metoaka, was reported to have stood to the side, scowling fiercely as she twirled in front of her father in her finery. Powhatan, however, gave smiling approval to his beloved daughter’s much changed appearance. Later Lady de le Warre was to present the Indian Princess with a chain and locket of gold with a small diamond set in the locket. Lady de la Warre observed that though Pocahontas had been taught from childhood not to weep, when she placed the locket around her neck tears came into the young girl’s eyes. She not only wore it from then on but was buried with it still around her neck seven years later.

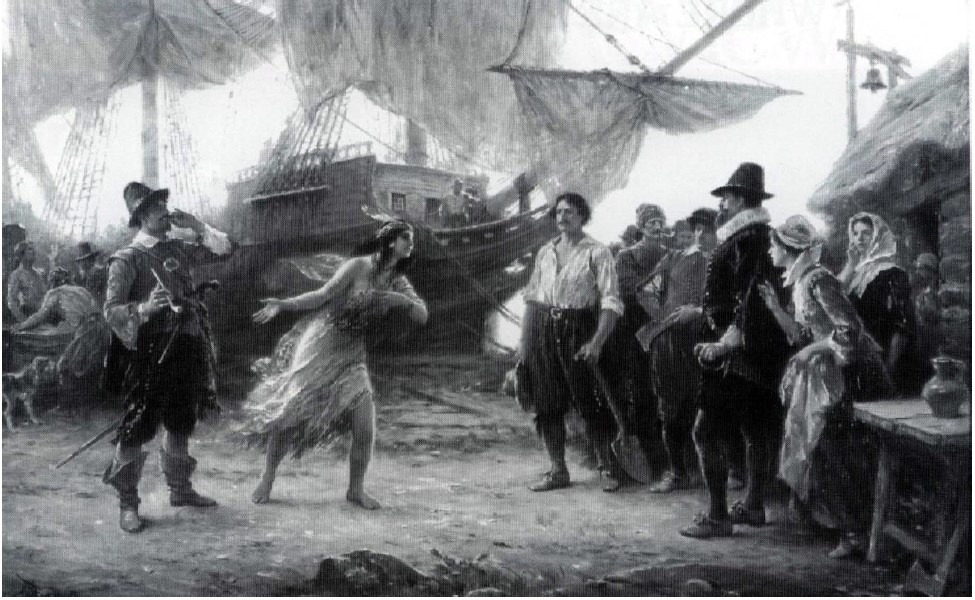

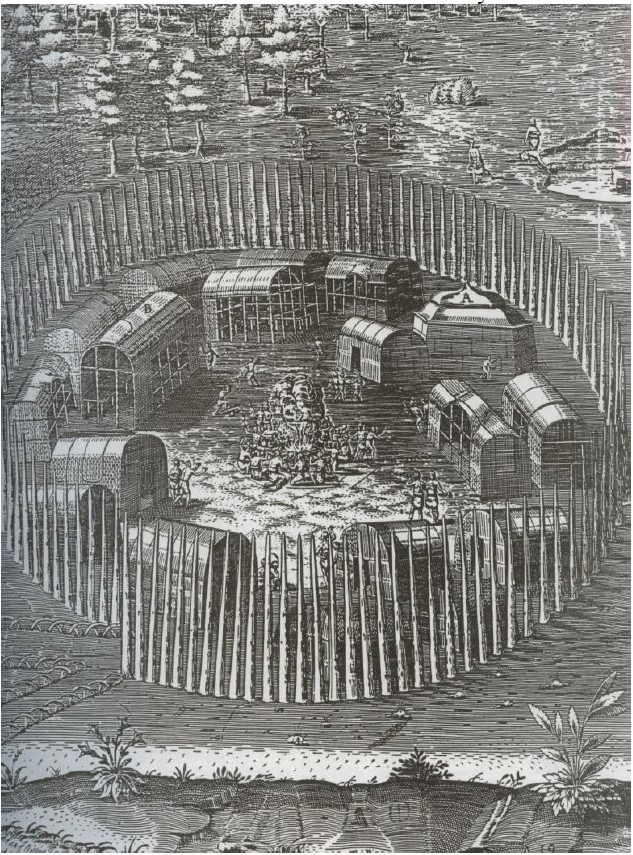

A most unusual chapter in the life of Pocahontas takes place in Stafford County. In 1611, she was visiting Chief Japazaws, King of the Patowmack in one of the largest villages in the Powhatan Confederacy, located at what is now Marlborough Point. (The above picture of a palisade village looks much like that at Marlborough Point.) There are several accounts as to why she was in Stafford. According to one member of an English expedition, she was here representing her father on a trade mission. There is also evidence of a growing estrangement between Pocahontas and her father over her involvement with the English colonists at Jamestown and he may have wanted to put some distance between her and the settlement. Whatever the reason, she was at Marlborough Point. Captain James Argall, learning of her presence there, sees an opportunity to force agreements between the colonists and her father by taking her captive. Sailing to the Potomac village he involves King Japazawas and his wife in the plot to get the Princess on board the English ship anchored at the Point. Among other trade goods he promises Japazaws wife a new copper kettle if she can persuade Pocahontas to come on board. This is accomplished by an appeal from the older woman to accompany her so that she will not be the only woman in the boarding party. Once aboard Pocahontas is seized and locked in the gun room for the trip back to Jamestown.

Ransom notes are dispatched to Powhatan and once again we are faced with conflicting accounts of what happened. We know that Powhatan was promised that his daughter would be “well used” and treated as an honored guest in the settlement. Some say the proud chieftain refused to meet the demands for ransom and his daughter was forced to remain in Jamestown. Other accounts say that while all the demands were met by her father, Pocahontas chose to stay on in the English settlement. Perhaps because of the political delicacy of her stay it was not Lady de la Warre, her friend, that became her hostess this time, but Lady Dale, wife of Sir Thomas Dale, Chief Marshall of the Virginia Colony.

The Dales employed the Rev. Alexander Whitaker, a graduate of St. John’s College in Cambridge to teach the daughter of Powhatan English and the Christian religion. Both were successful efforts. If the ability to adjust to change in culture and environment is a gauge of intelligence, Pocahontas was a brilliant young woman. She moved easily into the English society of Jamestown. The widower, John Rolfe, had recently come into the colony and he was asked to help in the teaching project by the Rev. Whitaker. Rolfe said of his pupil, “She had a capableness of understanding and aptnes [sic] and willingnes [sic] to receive any good instruction.”

In March of 1613 Pocahontas became a member of the Anglican Church and was baptized on the arm of Governor de la Warre as Rebecca, a Christian name to supplant her native one. For the occasion she wore a white silk gown which she was later to wear for her wedding. On July 13 of 1613, a special service was held in Westminster Abbey attended by King James and Queen Anne. This was to give thanks for the conversion of the “New World Princess” to the Christian faith.

John Rolfe, the widowed father of two young children found much to like in Pocahontas other than her “aptness for learning.” He speaks of “Christian passion” for the young woman as he writes home to relatives in England. However, as the wedding draws near he writes them apologizing for marrying “out of his race.” Pocahontas and John Rolfe were married in Jamestown on September 11, 1614.

Once again the adaptability of the young Indian woman was shown as Pocahontas moved easily into her role of stepmother and mistress of the new house John Rolfe had built for her. She had two servants, a cook and a nursemaid for the children. Young Barbara Rolfe remembered later that it had been her stepmother who had heard the lessons and instructed them in religion. In September of 1615, a son was born to Rebecca and John Rolfe. He was named Thomas. In a letter to England, Lady Dale remarked on the fact that Rebecca showed an unusual amount of affectionate regard for her young son, carrying him everywhere with her rather than leaving his care to servants as most of the mothers of well born young English children did.

When young Thomas was about six weeks old he was carried to meet his famous grandfather. Pocahontas wore Indian dress and John Rolfe wore buckskins as they took their three young children to visit the Chickahominy settlement. There were probably all the appropriate ceremonies to welcome the son of an Indian Princess and a week later the family returned to Jamestown accompanied by a royal escort of Powhatan’s braves. Barbara Rolfe noted later that her stepmother and the rest of the family made trips frequently to the Indian village over the next year. She described the happiness the whole family knew during the year they were together in Jamestown, but it was to end as Pocahontas took on the role of dutiful wife as well as loving mother in October of 1616.

All London had been regaled with stories of the Indian Princess who had become Lady Rebecca Rolfe on her conversion to Christianity and marriage to a prosperous Virginia tobacco planter. The London Company now implored John Rolfe to bring her to England. They felt her presence would bring investments flowing into their New World ventures and of course they promised that some of these would support Rolfe’s new experiments with growing tobacco in the colony.

In one of America’s first “public relations” appearances Pocahontas and her family arrived in London in October of 1616. Hundreds of London commoners crowded the dock and were amazed as Pocahontas smiled and waved to them as she disembarked. They were used to going unnoticed by the aristocrats of London society. In London they stayed with Lord and Lady de la Warre who had returned from the colonies a year earlier. She was introduced by them to London high society. Lady Dale wrote this about her attendance at a party given in her honor by the Earl of Somerset. “She wore a gown of emerald velvet. Pinned to the gown was a diamond brooch loaned by Lady de la Warre. Her luxuriant black hair was piled high and secured with tiny gold and diamond pins.” More importantly those in attendance were amazed at her perfect English, her flawless poise and her charm and graciousness to all about her.

Pocahontas became the sensation of London, being invited to Whitehall to meet King James and Queen Anne. Lady Dale was worried when Pocahontas refused to wear the powdered wig required for court receptions. Those who had to comply with this social protocol felt the requirement was based on an effort to make King James’ own bald head appear less conspicuous.

Pocahontas refused to cover her shining dark tresses, but she need not have worried, her charm impressed not only the King and Queen but young Prince Charles as well. After this first reception she was invited to private luncheons and teas with Queen Anne and attended theatre with her husband and Prince Charles.

Investments of the aristocrats in the expansion of the Virginia Colony brought joy to the London and new capital for investment in Rolfe’s tobacco enterprises, but Pocahontas longed to return to Jamestown. According to Lady de la Warre, Pocahontas awoke screaming on September night in 1617, her cries roused the entire household as she implored her husband to take her and the family back to Virginia t once, she had dreamed that she would not see her home again. John Rolfe immediately began booking passage for the family to return to the New World and they left London several weeks later.

A farewell party was given by the King and Queen and all the guests applauded as Pocahontas entered on the arm of Prince Charles dressed in ivory satin trimmed in ermine. Many of the guests present that evening remarked on how thin and pale the Princess had grown. One of her last visits in London was to the ailing Sir Walter Raleigh in the Tower of London. It is reported that he questioned her at length about the success of the new English colony that now seemed to be flourishing on the coast of North America. The de la Warres were present to see the Rolfe family off on November 4th. A day later they had the sad duty of meeting the ship as it brought Pocahontas’ body ashore at Gravesend about twelve miles outside of London. The Virginia Princess, who had created a sensation in England, was never to reach her homeland again. She had died the night before as the ship made its way out into the English Channel. A stunned John Rolfe had wanted to take her body on to Virginia, but he was persuaded it could not be preserved for a 30 day voyage. A funeral was held at Gravesend. Queen Anne and Prince Charles attended the services along with the de la Warres and Lord and Lady Dale.

Though the Princess was never to come back to her native Virginia, her son Thomas Rolfe did. He graduated from Oxford in 1633 and in 1634 returned to the Colony he had left before his second birthday. He lived on the plantation built by his father and soon after his arrival went to visit his cousins along the Chicahominy River. Proud of his Indian heritage, be became fluent in the Algonquin language of his relatives and they exchanged frequent visits throughout his life. He married in1637 and by 1640 was one of the most influential tobacco planters in Virginia. Among the direct descendants of the Indian Princess Pocahontas are many well known Americans including our third president, Thomas Jefferson.

Compiled from lecture notes by Marion Brooks Robins