The Women’s March

By Marion Brooks Robinson

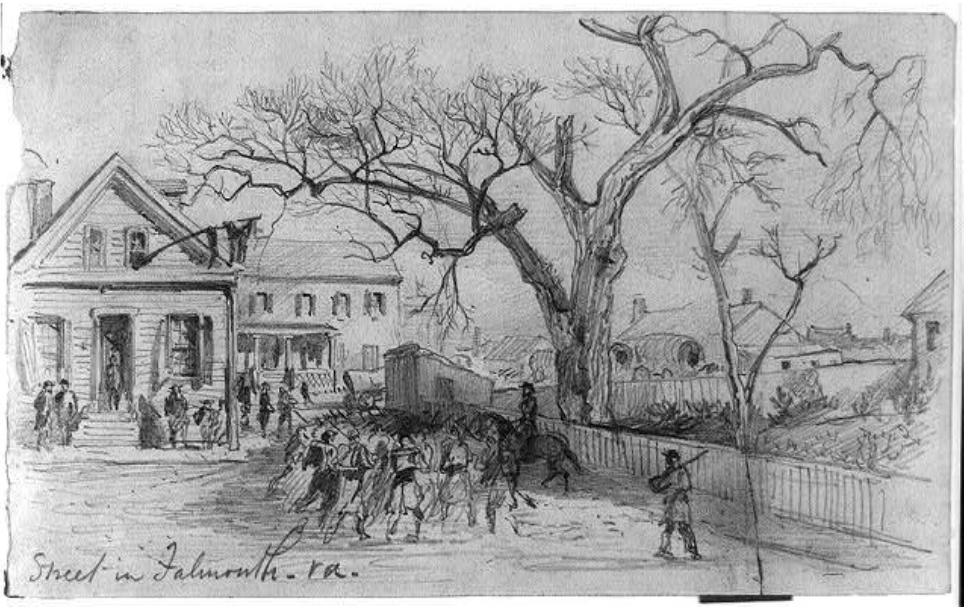

There are several interesting “oral history” stories from the Civil War period in Falmouth that have been passed down through several generations of my family. One concerns the period after the Battle of Fredericksburg in the spring of 1863.

Celebrations of the Confederate victory in December of 1862 had been private affairs since the town was under union occupation. Cut off from Fredericksburg by the destruction of the Rappahannock River bridges, citizens already were experiencing food shortages and were looking forward to the spring perch and herring runs in the Rappahannock. Ladder traps were in place just south of the fall line and, as in past years, residents expected the traps to yield 20 to 25 bushels of fish each day. Some of the fish would be eaten fresh, but most would be salted down for anticipated “hard times.”

Falmouth men knew the spawning run was good that spring and were surprised to find 20 or 25 fish instead of that number of bushels in their traps. In a few days’ time, they learned that Union Army officers, then in residence at Clearview and Carlton, were coming out at dawn to appropriate the fish for themselves and their staffs. Falmouth men felt that this “appropriation” of fish was nothing less than “stealing” their anticipated source of food. One of the men, who supposedly was known but never named to the officers, took his own action against the “stealing.” One morning in early April, hiding behind low willows along the Falmouth bank of the river, he fired on and killed two of the Union soldiers removing fish from the traps. According to reports, General Hooker was livid about the killings because one of the victims was the chief cook of his camp. He sent out word that if the Southerner responsible for the Union deaths was not turned over to him by 6:00 P.M. the town of Falmouth would be put to torch.

My great-grandmother, Hannah Jones, was angered by this order and organized about 14 local women for a “march” on Clearview, where General Hooker was supposed to be camping at the time. When the women arrived on the hill, a sentry told them that the general would be unable to see them. Undaunted, they “marched” up to sit on the back porch of Clearview and declared that they would wait. After they had sat there for more than three hours, the general rode up. My great-grandmother, acting as spokeswoman for the group, immediately assailed General Hooker for ordering the homes of innocent women and children to be burned. She pointed out that as good Christian women, she and her colleagues felt that the killings had been a wicked act, but that the punishment of an entire town would be just as wicked and must be halted.

Evidently impressed by the women’s petition on behalf of the town, the general immediately recalled his burning order and Falmouth escaped the Union wrath. I doubt, however, that the men recovered the use of their fish traps that spring. While the military history of the area offers no direct proof of General Hooker’s orders to burn the town of Falmouth, these dealings with local citizens seldom were recorded in the military logs. Itis known that General Hooker had taken command of the Army of the Potomac in January of 1863 and was in the Falmouth area that spring.