Reconstruction - Overview

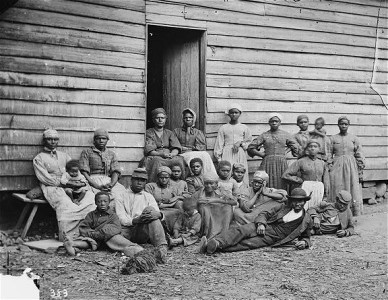

Reconstruction is generally referred to as the period following the Civil War ending in the return of the Southern states to Constitutional, legal and political viability. Some historians date Reconstruction from the war’s end; others date it from 1863, when the Emancipation Proclamation (January 1st) went into effect and when Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address was delivered (November 19th). The Emancipation Proclamation initiated the process of freeing all of America’s 4,000,000 enslaved persons by 1865. The Gettysburg Address is considered to be a virtual “Second American Constitution” – reaffirming Revolutionary liberty and launching “a new birth of freedom” based on legal and political equality of all the people and “government of the people, by the people and for the people.” The people had been expanded from post-Revolutionary white males to include immigrant males and freed American Americans. Ironically, still not included were women. A still greater irony was this reaffirmation of liberty – generally meaning the ability to go through life unimpeded by government or other people – and extension of legal and political equality also led to a greater historical involvement by the Federal government in the lives of the people. No longer would Federalism be limited to centralization of the nation’s financial, military and diplomatic affairs. This period would create a host of new demands and encroachments into the rights of states and people.

For Virginia and Stafford, Reconstruction began with a military and a political occupation. Virginia became Military District 1, and all authority was vested in military government. The wartime shadow government of the state was installed in Richmond and Virginia began a new period where every right and privilege of the past was gradually returned to the people and their government. Federal troops backed the authority of the state government and a national entity, the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, zealously ensured the postwar protection of the downtrodden – former enslaved and poor whites. Political parties and factions were realigned in Virginia. The old Democratic Party was now referred to as “Conservatives” and “Funders” (pertaining to handling wartime debt). A new political party, the “Readjusters” rallied around a coalition of former Whigs, Republicans, African Americans and Poor Mountain Whites. The Readjuster Party, ironically led by former Confederate general William Mahone, rose in power during Reconstruction, became basis of the Virginia Republican Party, and wielded power until the 1890s resurgence of the Democratic Party and the launching of its machine by Thomas Staples Martin. Thereafter the Democratic Party was returned to full power and political domination under the subsequent Byrd Machine until the 1970s.

Lost, until recent years and scholarship, was the ultimate point of Reconstruction – reunification of American and reconciling the North and South – pitched enemies in our bloodiest war. Ultimately reunification and reconciliation created a greater national political need than civil rights and returning to “business as usual.” The large number of solid civil rights enactments – including the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments and a substantial number of civil rights laws and court decisions – were subordinated to the need to rejoin North and South. As reconciliation required the willing participation of the South, its needs and wants had to be considered. The greatest of these was political power. If the Civil War’s results, especially civil rights, were carried out to logical ends,

then a majority of populations in the Deep South’s states would have been African Americans. Even in those states, such as Virginia, where black populations approached more like 30 percent, these constitute substantial constituencies to be reckoned with. Federal enforcement could have ensured political equality, but the drive for reconciliation required Southern acquiescence. As reconciliation efforts were largely led by war veterans through joint reunions and joint commemorations, the Southern views of the war and Southern views on race had to be accepted, at least to some extent. This excluded nearly 180,000 black veterans from credit and participation, and set the conditions to restore resurgent Democratic Party dominance in the returned Southern states. Democrats returned to Congress with restored seniority and power, and black civil rights dissolved in national political expediency.

In Stafford, Reconstruction took several forms: 70 percent of Stafford’s black population departed for Northern spaces by 1870 (only five years from the end of the war). Many risked poverty in the North to avoid political subjugation in Virginia. Economic recovery, gradual at best, did bring relative prosperity and greater opportunity to working class people no longer competing with the enslaved. Productivity increased and something of a return to normalcy transpired. Stafford saw a rise in creation of black churches, which provided a basis for community, mutual support and better education for black youth. Reconstruction was officially declared over by 1873, but more was lost than had been gained in civil rights.

By the turn of the century, with the political demise of the Virginia Readjusters/Republicans, conditions were ripe to “permanently” disenfranchise blacks and as many poor whites as possible. If these groups, former voting blocs of the Readjuster coalition, could be cut off from political power, then the dominance of the Democrats could be assured. The Virginia Constitution of 1902 sealed that process. Poll taxes and elaborate voter-blocking schemes requiring detailed constitutional knowledge explanations – only war veterans (North or South), in dwindling numbers by then, were exempted – contributed to keeping blacks and poor whites from voting. At best, some delegates argued that this disenfranchisement was dangerous to liberty as this approach could ultimately be extended to anyone. This opened the gates to expanded Jim Crow laws; “separate-but-equal” education (which was never equal); and wholesale segregation. Ironically, the greatest period of racial bigotry and oppression was in the 1890s-1920s. Calls for improved civil rights in the country after World War II brought on increased demands for doing away with “separate-but-equal” schools and segregated facilities. Greater political assertiveness in America, Virginia and Stafford were detectable. The landmark 1954 Supreme Court Decision, Brown v. Board of Education, toppled the “separate-but-equal” doctrine, and opened the way for de-segregation. Virginia’s “Massive Resistance” efforts delayed implementation for over a decade.

The 1960s saw a focus on civil rights which paralleled Reconstruction and substantial steps were taken to carry out the measures proposed by President Lincoln 101 years’ earlier.