Union Occupation Overview

Stafford County saw three major Federal occupations during the Civil War: April-September 1862; November 1862-June 1863; and April-June 1864. By far the largest and most significant occupation was November 1862 to June 1863. This involved the Union Army of the Potomac’s arrival and participation in the battle of Fredericksburg (December 11-15, 1862); post-Fredericksburg recovery; the “Mud March” (January 20-24, 1863); the strategic pause (January 25-April 27, 1863); the battle of Chancellorsville (April 27-May 6, 1863); and final encampment for departing for Gettysburg (June 12, 1863).

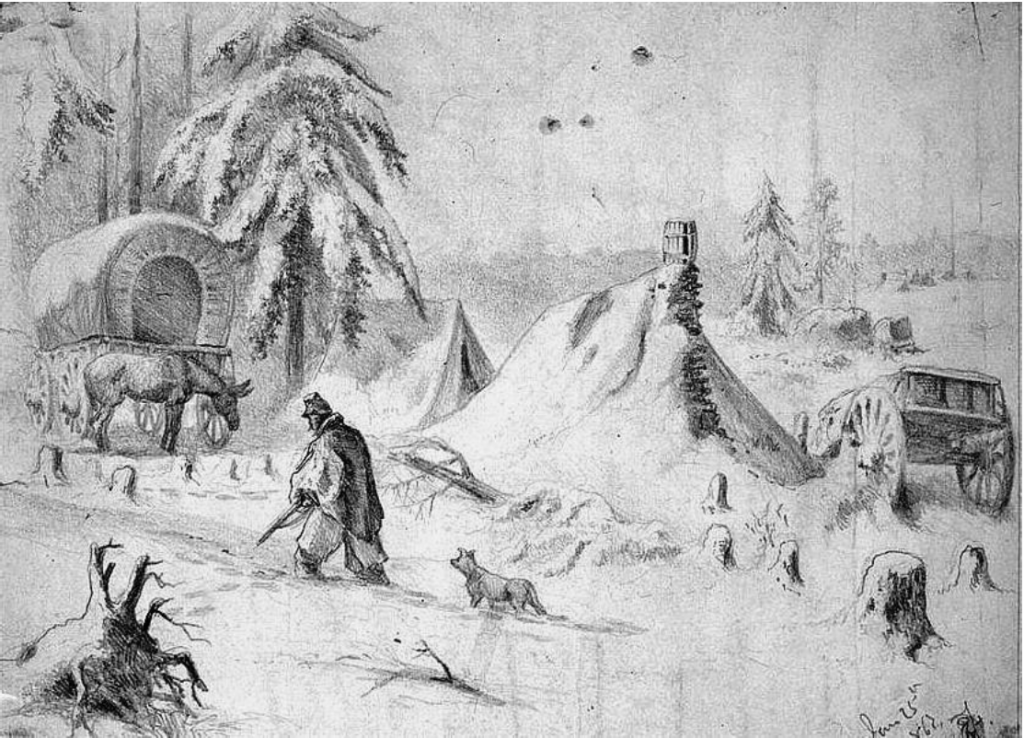

Of these, the most significant period was the strategic pause which began on January 25, 1863, and ended on April 27, 1863, when the army marched off on the Chancellorsville Campaign (Chancellorsville and Second Fredericksburg). On December 25, 1862, Major Rufus Dawes, 6th Wisconsin Infantry, prophesized that the subsequent period would be the “Valley Forge” of the war. Over the subsequent months, at least a thousand other Union soldiers and several reporters saw the same linkage between Valley Forge in the Revolution and what was happening in Stafford County that winter. In both cases armies fighting for the salvation of America, hit bottom in morale and fight capacity following battlefield defeats and faced a “landscape of defeat.” Washington’s army of 10,000 buckled down for a long, hard winter and built 2,000 huts; demanded better training and discipline; curbed desertion; and cared for the sick and wounded while its leaders fought off infighting, backbiting, political intrigues, congressional meddling, and popular discontent. They actively patrolled, gathered supplies, and made plans for improved performance. The resurgent Colonials came forth the following June and defeated the British at Monmouth. Valley Forge was a non-battle turnaround and turning point for Washington’s army’s revolutionary struggle. The Army of the Potomac, “Mr. Lincoln’s Army” of 135,000 buckled down for a long, hard winter and built 30,000 huts; demanded better training and discipline; curbed desertion; and cared for its sick and wounded while its leaders fought off infighting, backbiting, political intrigues, congressional meddling, and popular discontent. They also attacked the Copperhead antiwar movement with unit resolutions, letters, and homefront speeches. The army actively patrolled, gathered supplies and made plans for continued operations and improved performance. The resurgent Federals came forth the following May and nearly defeated the Confederates at Chancellorsville and then reemerged in June and defeated Lee’s army at Gettysburg. Everything that happened at Valley Forge in 1777-1778 happened in Stafford County in 1862-1863.

When Major General Joseph Hooker assumed command of the Army of the Potomac on January 25, 1863, the picture could not have been darker or the future bleaker. What was considered the Union’s premier army in the most important theater of operations could not win. Some 85,000 of his 135,000 man army were unaccounted for. At least 25,000 had deserted. Enormous numbers – at one point 45,000 lay in hospitals. President Lincoln expressed doubt and distrust in a letter to him. His army had not defeated their Confederate opponents through 20 months of war. Distrust and insecurity was found in every piece of communication. Teamwork and discipline were in limited supply. Only the

best units hung together. The saving grace for the army was its patriotism and its faith (both religious and political) that America would survive. The army maintained a deep strain of perseverance; but it was hovering over defeat. Support at home had dwindled to the point of bare existence. Families shipped civilian clothes to their soldiers and urged desertion. An antiwar movement declared their war unwinnable and immoral; opponents to the administration and the war gloried in every defeat – none more than Fredericksburg. The army’s leaders were not pulling together and that translated to every lower level. The battle experience and lessons learned acquired thus far were not translated into improved organizations or war systems. In a few places, such as in the medical area, reforms had been initiated. The army was at a fork in the road. One road led to defeat and destruction of the nation, and the other started with reform, reorganization and resurgence. What was most needed was a surge in military leadership complemented by effective political leadership. During the following 93 days in Stafford County, those were provided by Generals Joseph Hooker and Daniel Butterfield; and President Abraham Lincoln.

The leadership began with the basic needs of the soldiers – better and more varied food; physical care of the sick and wounded; effective shelter and field sanitation; more timely pay and reward (promotions, medals, furloughs); better training and discipline; and rest and recreation. The first step was to instill personal pride, and to build that into unit pride. Along with those measures, the army was reorganized (eliminating a layer of command; creating a cavalry corps capable of independent action; creation of a military intelligence structure); reformed (tactical logistics, medical, transportation, bridging, provost marshal); and revitalized (material and spiritual nourishment). Drills, inspections, marksmanship training, and actual conduct of operations (cavalry, infantry and combined raids and patrolling; rear area sweeps; civilian-military actions). Poor officers and soldiers were court-martialed and dismissed. Non-judicial punishments were meted out to miscreants. Good performance of units and soldiers was rewarded. Efforts to study the proper loads for men, pack animals, and wagons were undertaken. Weapons and equipment were cleaned and inspected. Every soldier was checked for basic items (e.g., ammunition in pouches) and shortages were made up.

Even those who doubted Hooker’s and Butterfield’s leadership were impressed – they noted that they had never seen such a large force turned from despair to fighting effectiveness in such a short period of time. When the army left for Chancellorsville, it was a rejuvenated force and it nearly defeated Lee’s army for the first time. Because of the extent of resurgence, Chancellorsville was a different kind of defeat than Fredericksburg and the “Mud March.” This time the army was angry and frustrated over letting success slip through their fingers; and they were ready to fight again quickly. As it turned out, that was at Gettysburg, where the “Valley Forge” army defeated Lee’s army for the first time and seized the strategic initiative from the Confederacy permanently. The war would require another 20 months to bring to an end; but, the corner had been permanently turned and the Union army would deliver the blows which led to victory and the salvation of America – both the one that existed and the one that it would become in the twentieth “American Century.”